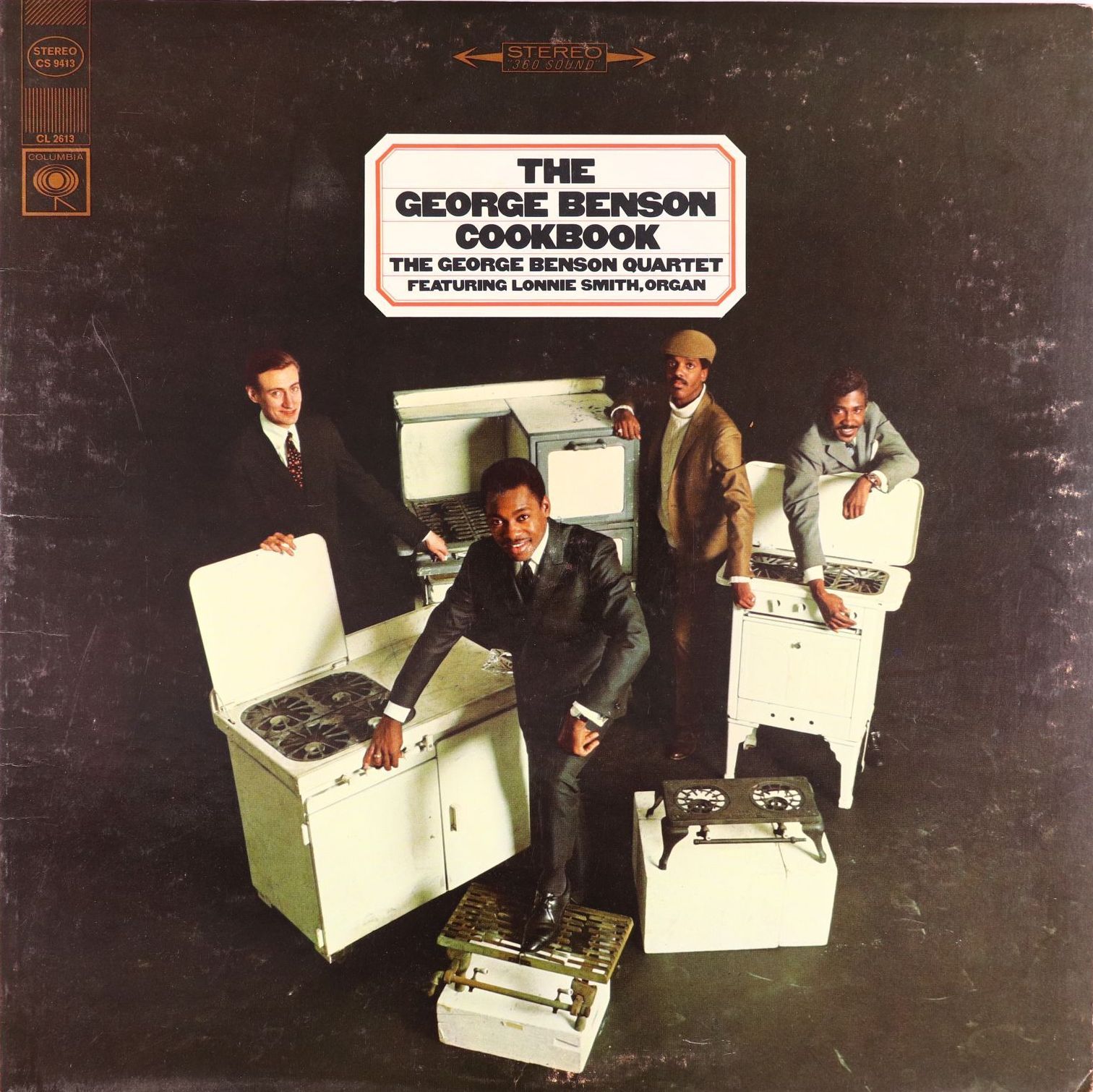

There are two, maybe three or four George Bensons. However, for straightforward jazz fans, there’s only one: the cat that made gritty, in-your-face soul jazz albums like 1966’s Cookbook.

Personnel

George Benson (guitar), Ronnie Cuber (baritone saxophone), Lonnie Smith (organ), Jimmy Lovelace (drums), Marion Booker (drums)

Recorded

From August 1 – October 19, 1966 at Columbia Studio, NYC

Released

as CS 9413 in 1967

Track listing

Side A:

The Cooker

Benny’s Back

Bossa Rocka

All Of Me

Big Fat Lady

Side B:

Benson’s Rider

Ready And Able

The Borgia Stick

Return Of The Prodigal Son

Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid

For those fans, listening to George Benson after 1966 is like the obligatory New Years Drink from your employer.

Damn, is guessing who’s been under the sheets with whom the only game around here?.

Ok, one might answer the demure jazz buff,

next time bring your turntable, light things up a bit, you crank. And the fifty-something who grew up on a diet of Average White Band and Santana might add,

hey pal, George Benson did

record some awesome stuff after ’66.

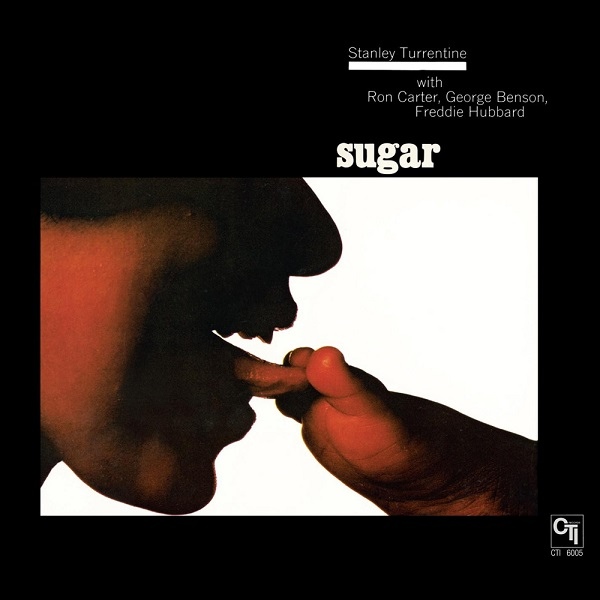

Sure he did. Except most of it is drowned in an overstuffed sound soup of strings, harp, flute, synth and, yuk, strings from the synth. A&M and CTI albums like The Other Side Of Abbey Road (1970) and White Rabbit (1972) are, notwithstanding the heavyweight line-ups of, among others, Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter, technically exceptional elevator muzak affairs, no less. If it wasn’t for the greasy, steamroller beat of drummer Idris Muhammad, 1968’s The Shape Of Things To Come would’ve been nothing more than schlock for the building constructors working on the streets where you live. Then again, few are prepared for My Latin Brother from Bad Benson (1974), a smoking, exotic and sizzling Latin tune with a quintet line up from the matured guitar player. And the highlights of Benson’s big break as a smooth jazz star in 1976, collected on Breezin’, are, despite their schmaltzy coating of synth, pretty darn good courtesy of the experienced, first-class session players – take So This Is Love. The only thing it needs is the voice of Barry White. Next thing you know one of sixteen vestal virgins appears from out of the blue, ready to sign up for Procol Harum’s harem.

As early as early 1968, when Benson was still a soul jazz guitarist, there were hints of radio-friendly formatting. His album Giblet Gravy has both the low-down dirty blues, injected with typical lightning-bolt fingering, of Groovin’ as the saccharine take of the ultimate crowd pleaser, Bobby Hebb’s Sunny. In fact, he’s singing an r&b-type version of All Of Me on Cookbook that could’ve done well on the jukebox market. George Benson has always been the kind of performer that succeeds in recording bubblegum ditties in the afternoon and play steamin’ r&b at night. Organist Greg Lewis told Flophouse that he regularly tried to sit in as a woodshedding Hammond B3 player in the early nineties in a Manhattan club, sometimes succeeding to replace one of the accomplished organists for a tune or so. Occasionally, Benson, at the height of his fame, would drive his limousine up the sidewalk, park, get in and join the band on stage. Nobody cut George.

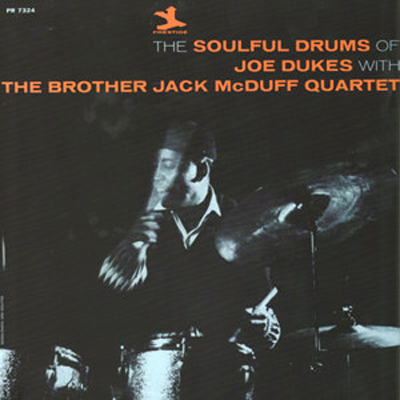

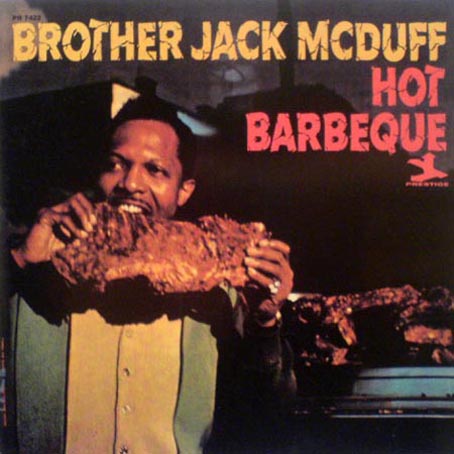

Cocksure at heart. Benson was like that when he first hit the scene as a sideman with organist Brother Jack McDuff in late 1963. By no means arrogant, instead playing with a joy of discovery that is contagious. In McDuff’s band, the youngster, who sang professionally as a kid, still played the kind of r&b guitar style from his teenage years, although the influence of his heroes Charlie Christian and Grant Green (interpreted in fast forward motion) were readily discernible. Displaying quicksilver runs, a biting attack, torrents of foul-mouthed but impeccably placed blues phrases, Benson heated up both studio and stage to temperatures uncommon even in New Jersey or New York City summer season. Dig Benson’s fireworks on YouTube, footage of the McDuff Quartet’s 1964 performance at Antibes, France, here.

After a string of albums with McDuff and his debut album on Prestige, The New Boss Guitar Of George Benson, the guitarist had signed to Columbia, releasing It’s Uptown in 1966, with one of those grandiose subtitles I’m sure musicians weren’t too fond of, The Most Exciting New Jazz Guitarist On The Scene Today. It was a thoroughly exciting group that Benson had assembled and baritone saxophonist Ronnie Cuber, organist Lonnie Smith and drummer Jimmy Lovelace (alternating with Marion Booker) also gathered for the Cookbook session, still more tight-knit as a unit, delivering a hot barbecue of spicy ribs and saucy side dishes. There’s the opening tune, The Cooker, a strike of stop-time thunder, evidence of the group’s effortless breakneck speed swing and Benson’s fast-fingered blues wizardry. Perhaps already the highlight of the album, which yet doesn’t take anything away from the remainder of the repertory, including other Benson originals like the gentle Bossa Rocka and Big Fat Lady, a perky r&b tune that could easily pass for the background to Jimmy Hughes on Fame or Hank Ballard on King.

Benson gets his kicks with licks on Benson’s Rider, a boogaloo-ish rhythm perfectly suitable for the deeply groovy Lonnie Smith. Benson wrote the The Borgia Stick for a mafia television series, a lush greenery for the mutually responsive soul jazz cultivators, who are effectively aroused by sections of tension and release. The nifty Jimmy Smith tune Ready And Able presents the burgeoning talent of baritone saxophonist Ronnie Cuber to full effect. He’s like the cookie monster that’s gotten a shot of rhythm&blues, soulfully eating up the breaks off the I Got Rhythm changes.

The other horn player on the date, Benny Green, happened to walk into his friend George Benson on the street prior to Benson’s session. Benson invited Green over to the studio to join the proceedings. Such is the unique nature of jazz and its practitioners, that sheer coincidence may be turned into a musical advantage. Green’s uplifting, swinging style is an asset on Benny’s Back (which was written on the spot by Benson and refers to the fact that Green was also present on Benson’s first Columbia LP) and the swing-styled jam Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid, the longest track on an album that keeps warming the hearts of ‘early-Benson-fans’ around the globe.