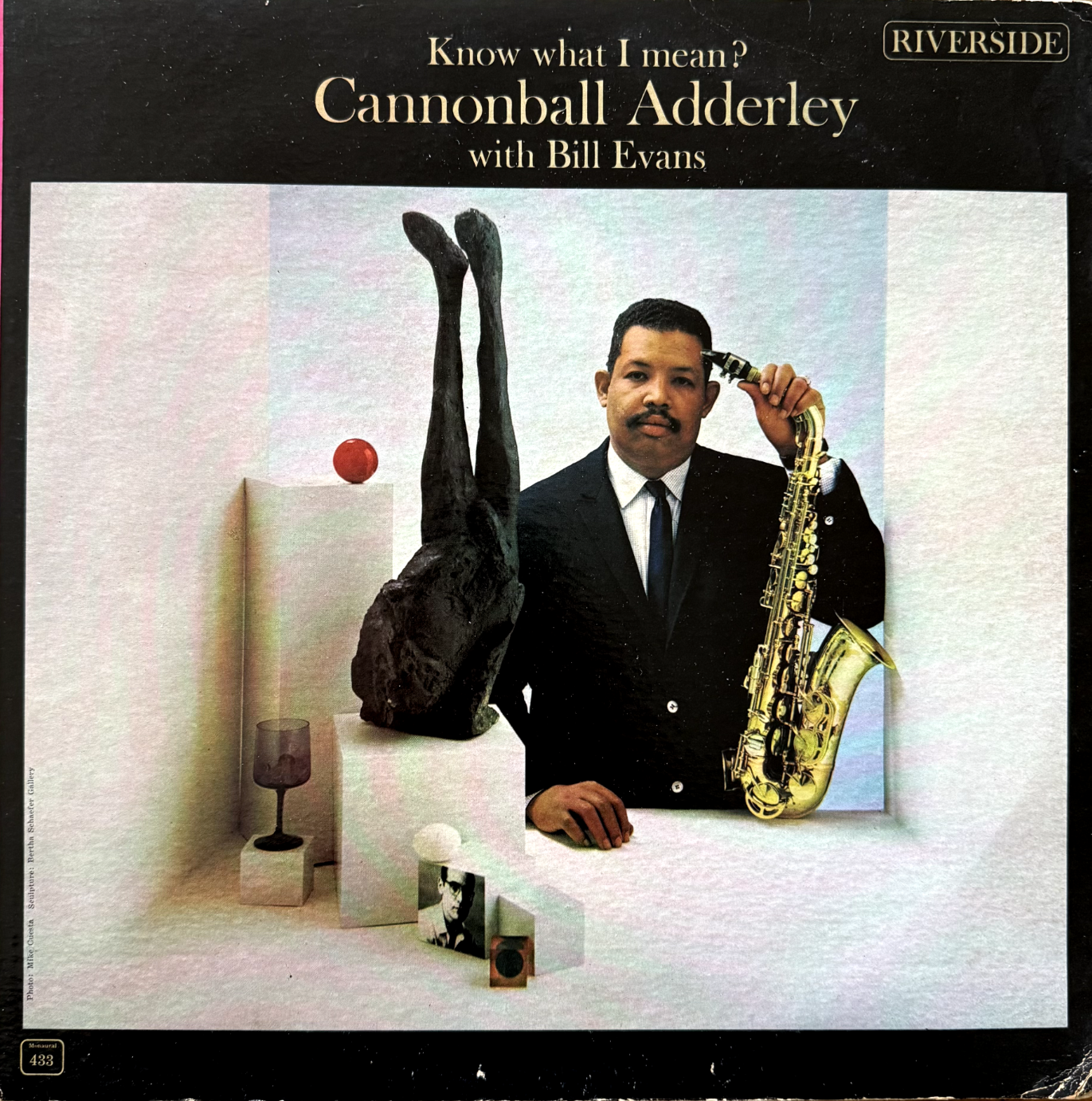

Yes, we dig.

Personnel

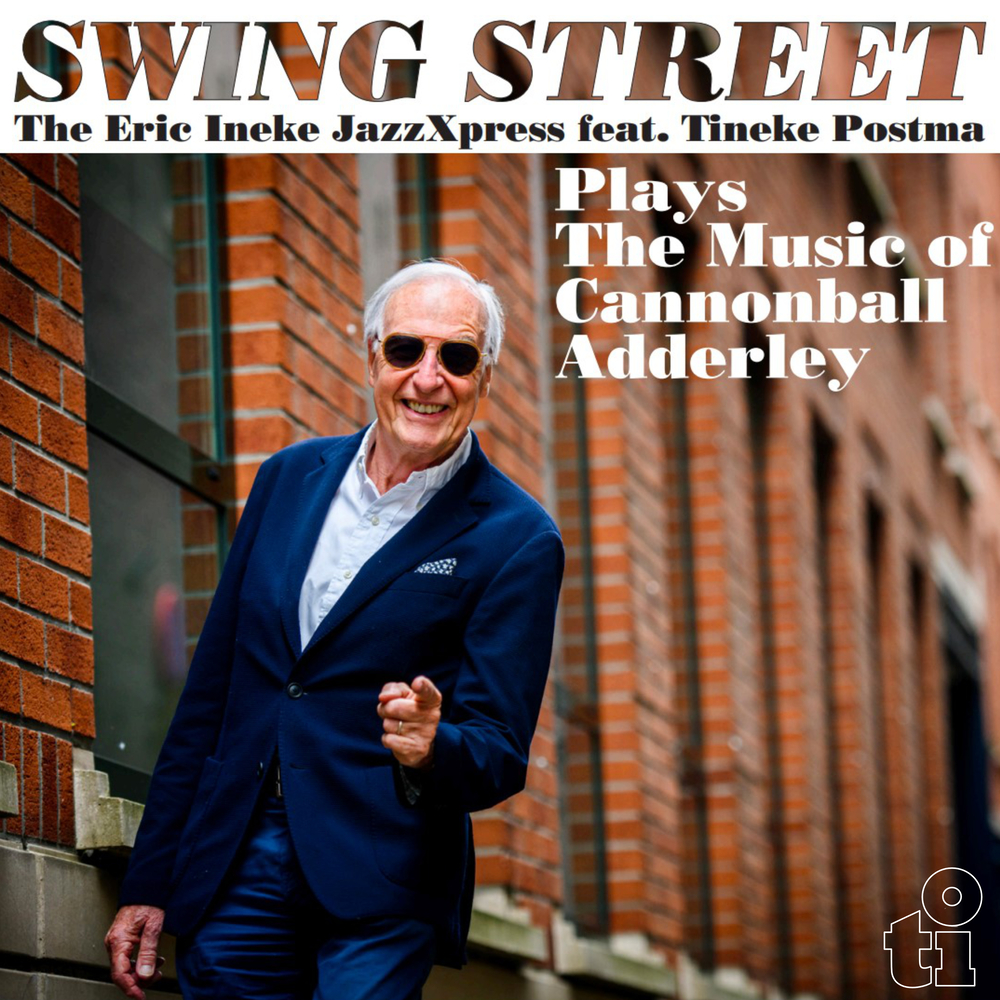

Cannonball Adderley (alto saxophone), Bill Evans (piano), Percy Heath (bass), Connie Kay (drums)

Recorded

on January 27 & February 21 & March 13, 1961 at Bell Sound Studios, NYC

Released

as RLP 433 in 1961

Track listing

Side A: Waltz For Debby / Goodbye / Who Cares? / Venice / Side B: Toy / Elsa / Nancy (With The Laughing Face / Know What I Mean?

Cannonball’s articulate introductions or conversations would regularly be injected with his catch phrase “Know what I mean?” A proper album title, according to Riverside label owner Orrin Keepnews, who got on really well with Cannonball and not only released many excellent recordings by either Cannonball or the Cannonball Adderley Quintet but also gave him a free hand as officious A&R guy – and loved to pair class acts from his Riverside roster like Cannonball and Evans. At that time, free from the constraints of a lousy contract with EmArcy, with his partaking in Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue, his own Somethin’ Else on Blue Note and soul jazz hit records Work Song and This Here on Riverside under his belt, Cannonball was in a very good place.

Cannonball had been acquainted with Bill Evans for a while. Besides Kind Of Blue in 1959, the alto saxophonist had worked with Bill Evans earlier in 1958 on Portrait Of Cannonball. An excellent record featuring an early, tentative version of Evans’s beautiful Nardis, hard-swinging (Philly Joe Jones in da house), it is somewhat the opposite of Know What I Mean?, which swings merrily, an aural reflection of a bottle of Prosecco, can’t you hear it pop and sizzle, know what I mean…

Portrait is the introduction of Bill Evans into the saucy realm of Cannonball, Know is Bill Evans pulling the sleeve of Cannonball, let’s go this way perhaps, my friend, it’s the land of milk and honey… Either way, intriguing and beautiful. Know also features bassist Percy Heath and drummer Connie Kay, the beat apex of the Modern Jazz Quartet, which gives you an idea of the direction this foursome was taking… Flexible and solid Percy, unassuming, alert Connie, who plays like a ballerina. It is true, it doesn’t swing like mad but it’s solid as a rock.

Highlights include the bouncy take of the Evans classic Waltz For Debby, featuring a lovely lively story by Cannonball, perfectly developed from courteous remarks to flirting and, one imagines, hot kisses. I love the playful melody of Clifford Jordan’s Toy, which clearly inspires the energetic Cannonball. Elsa is vintage Evans, a typically elegant, perfect synthesis of emotion and ratio. With Evans at the bench, Cannonball’s set of standards and originals is light as a feather, swings fluently, and you can see a delightful smile creeping upwards from Cannonball’s lips to his forehead like a sunrise.

Smiling broadly is all one can do when listening to this fruitful collaboration of jazz maestros.

Listen to Know What I Mean? on YouTube below: