They called him Brother Jack for a reason.

Personnel

Brother Jack McDuff (organ), unknown (alto saxophone), unknown (guitar), Garrick King (drums)

Recorded

in June 1982 at Parnell’s Jazz Club in Seattle, Washington

Released

as SBM 007 in 2022

Track listing

CD1:

Make It Good

Untitled D Minor

Déja Vu

Fly Away

Another Real Good’n

Blues In The Night

Satin Doll

Night In Tunesia

CD2

Killer Joe

Greensleeves

Take The A-Train

Wives And Lovers

Walkin’ The Dog

Lover Man

Blues 1&8

The ongoing revival of the Hammond organ is unescapable. The iconic B3 is omnipresent, occasionally integrated in the modified aesthetic of avant-leaning electronic artists but more often as the prima donna of roots music. Countless organ groove outfits roam the prairies of the land of grease from Los Angeles to Osaka, Milan to Jakarta and Rotterdam to Stockholm. All of them are influenced by the likes of Jimmy Smith, Jimmy McGriff, Lonnie Smith, Booker T. Jones and Cyril Neville.

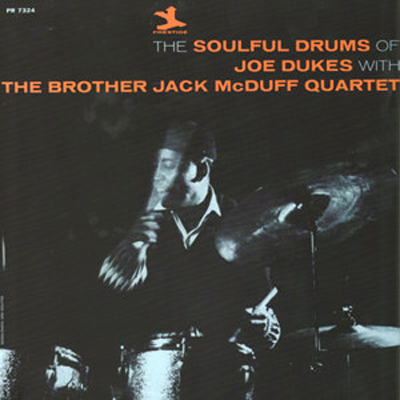

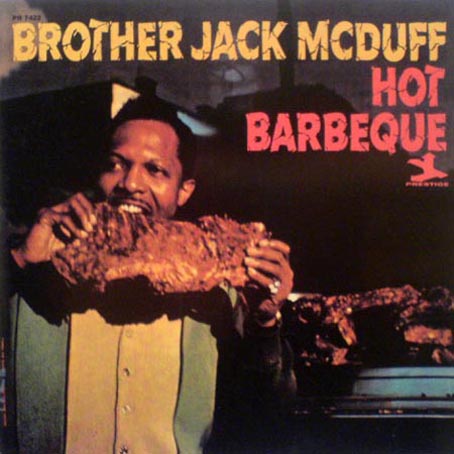

And, unmistakably, Brother Jack McDuff. As a hot modern jazz player, skilled bass pedal player and excellent arranger, McDuff was as all-round as one could get. Above all, Brother Jack (on his first live record for Prestige in 1964, McDuff stated during his introduction that they ‘call me Brother Jack for a reason, once you got that church in ya it’s hard to backslide all the way’) was an unparalleled churchy screamer, getting the club circuit flock excited to no end. One of the most popular organists of the golden age of soul jazz in the 1960’s, he reached a particular peak with his killer mid-sixties group of tenor saxophonist Red Holloway, guitarist George Benson and drummer Joe Dukes.

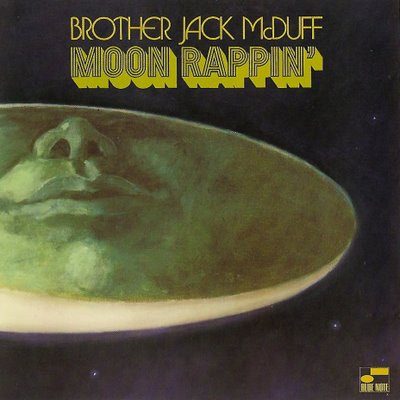

The dynamic journey of Laurens Hammond’s tone wheel-driven invention evolved from church life, theaters, the American household, black chitlin’ circuit of clubs to the jazz world and, eventually, soul, (prog) rock music and, in sampled formats, the world of hip hop. But by the early 1970’s, the dominating forces of disco and digital keyboards pushed the organ to the outer fringes of music and society. Some warriors dabbled with electronics, many of them quit, lone rangers kept bringing their top-heavy instruments to the remaining dives or supper clubs in tailor-made vans. Many finally rode the waves of the organ revival that was spawned by renewed interest in soul jazz, notably stimulated by English deejays, breakbeat producers and the ‘acid jazz’ movement. From then on, former popular organists as The Smiths, McGriff, Groove Holmes, Rhoda Scott and McDuff toured Europe and Japan to much acclaim. Back home, bands from guys like McDuff were breeding grounds for ‘woodshedding’ young lions. Among others, Cecil Bridgewater, John Hart, Chris Potter, Joe Magnarelli, Eric Alexander, Roy Hargrove and Art Porter learned to take care of business in Brother Jack’s relentless groove machine.

But by the early 1980’s, McDuff was one of the half-forgotten warriors, bereft of places to perform. However, as can be heard on Live At Parnell’s`, Brother Jack hadn’t lost his touch. By all means, he was swingin’ like mad and burnin’ like hell. Live At Parnell’s has an incredible back story, beginning with rusty private recordings of engineer Scott Hawthorne that dwelled on the internet in the late 1990’s to a brand-new sound palette engendered by Artificial Intelligence in 2022. Considering the apparent flaws of the original tapes, Live At Parnell’s sounds very good, apart from a relatively harsh saxophone sound and occasional distortions of Brother Jack’s Leslie Speaker. This is not bootleg fare but a genuine album.

And Brother Jack’s on a roll, assisted by top-notch “unknowns” on alto saxophone and guitar and drummer Garrick King. Hearing Brother Jack’s typical grit and grease, a couple of modern jazz classics and Ellingtonia, the audience at Parnell’s had it made. McDuff’s funky Fly Away is marked by a gorgeous gospel introduction. Another Real Good’n is the final installment of McDuff’s blues Good’ns that he started in his glory days, in this case McDuff’s eponymous band with Bad Benson, Holloway and Dukes. McDuff’s medium-tempo blues burning highlight abundantly shows that the altoist, guitarist and Garrick are worthy heirs.

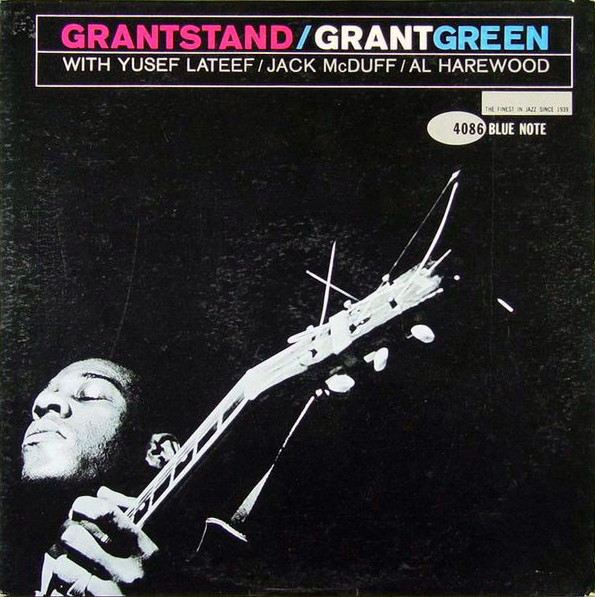

McDuff swings Night In Tunesia and Benny Golson’s Killer Joe to the ground. His sweetly rendered Satin Doll attests to a fine understanding of the Ellington aesthetic. Perhaps best of all is Burt Bacharach’s Wives And Lovers (check out Red Holloway’s version on 1964’s Cookin’ Together) which strikes a perfect balance between hot Summer and breezy Spring. Both the saxophone player, whose fervor reminds of Booker Ervin, and six-string bender, whose clear lines and punchy attack shadow box with the ghosts of Pat Martino and Grant Green, demonstrate a satisfying penchant for breaking out of the changes. McDuff is full of energy, never more so than during Duke Pearson’s Make It Good, putting chili pepper in everyone’s ass on the bandstand.

1982 definitely was a good year for Brother Jack, as this valuable release showcases abundantly.

Jack McDuff

Addendum: The sleeve of Live At Parnell’s mentions saxophonist Danny Wollinski and guitarist Henry Johnson. However, it turned out that this information most likely is incorrect. Henry Johnson did play with McDuff in the early 1980’s but communicated to Soul Bank Music’s executive Greg Boraman that he worked with none other than Ramsey Lewis at the time. So his tour diary said.

Boraman gave a copy to the recently deceased, lamented organist and multi-instrumentalist Joey DeFrancesco backstage at Ronnie Scott’s in London in July. Passionate B3 geek DeFrancesco had heard the tapes way back when and was enamored by the restored Live At Parnell’s release and stated: “Jack is playing his ass off on this date.”

Familiar with Garrick King’s playing, DeFrancesco said that he was 99% certain that it is King holding the drum chair at Parnell’s. Duly noted.

Find Live At Parnell’s on Soul Bank Music here.