FRIDAY NIGHT AT THE FLOPHOUSE –

There are worse things in life than hanging out with Sonny Stitt, Lou Donaldson, Eddie Harris and Rusty Bryant. All of them, with Stitt at the helm, played the electric Varitone saxophone and the Gibson Maestro Attachment in the late ‘60s, as a means to spice up their groove and experiment with sound.

Selmer introduced the Varitone extension on July 10, 1966 on a convention in Chicago. The Varitone is a control box for the attachment that fits on the bell of the saxophone, which is connected to a large amplifier. The player is enabled to achieve volume control, tone variations (allegedly 60 different sounds) and echo and tremelo effects. The octave effect – by pushing buttons the saxophonist can add a note an octave lower or silence the top note – is attractive, creating ways to experiment with timbre.

Stitt was fast. Merely two days after the convention, The Lone Wolf recorded his first album on Roulette with the use of the Varitone extension, What’s New!!!. Macabre ballad, lovely pun. Stitt used a killer band including trombonist J.J. Johnson and tenor saxophonist Illinois Jacquet (who himself gave the Varitone a go on two rare occasions on the album) and the rhythm section of guitarist Les Spann, pianist Ellis Larkin, bassist George Duvivier and drummer Walter Perkins, who are present as well on follow-up I Keep Comin’ Back. Parallel-A-Stitt was a small ensemble session featuring organist Don Patterson.

In the Downbeat issue of October 6, 1966, Stitt says, “It’s a revelation. It enables you to probe and find. It projects your own tone – not a distorted tone. Your individual sound doesn’t change. The mind will never get lazy with that help. You’re thinking all the time what to do next. All this gives you is something more to work with. It doesn’t help you to think better. It sounds so pretty. I love it. It’s the most beautiful thing that’s happened to me.”

“Big bands, organs, electric guitars, loud drummers can be quite frustrating to a person who’s trying to think while playing. With this new saxophone, a fellow can hear himself above anybody. He can play in a big ballpark and still be heard.”

Indeed, Stitt’s style remains the same, and while his Varitone records are not essential Stitt, he plays fluently supported by killer line-ups while toying with octaves and different sounds, prominently a hard and hootin’ sound which features a slight distorted edge that, despite his comments, I do hear. Nothing wrong with that. Anyway, unfortunately you won’t find anything of these three records on YouTube except the balladeering of What’s New. While checkin’ tunes after my vinyl listening session, I did come across a live performance of “electrified” Stitt with one of his greatest regular groups of Don Patterson and Billy James, playing The Shadow Of Your Smile at the Left Bank in Baltimore. Nice!

By 1970, likely Stitt’s contract with Selmer had run out. On Turn It On!, Stitt uses the Gibson Maestro Attachment. Hear him blast away on the title track with Virgil Jones, Melvin Sparks and Idris Muhammad.

Eddie Harris wanted his penny’s worth. The saxophonist played the Chicago Maestro Attachment on Plug It In! and Silver Cycles. Harris added the Echoplex, which could provide multiple tape loops which played back the recorded sound at constant intervals. It was therefore possible to play new melodies over the basic motif. Harris used the attachments to the benefit of his hodgepodge of soul and avant-leaning jazz of that period, like Lovely Is Today, Free At Last and

Coltrane’s View. Anything goes with Eddie, lots of grease and lots of feverish vibes and arguably the most interesting electrified player of this bunch.

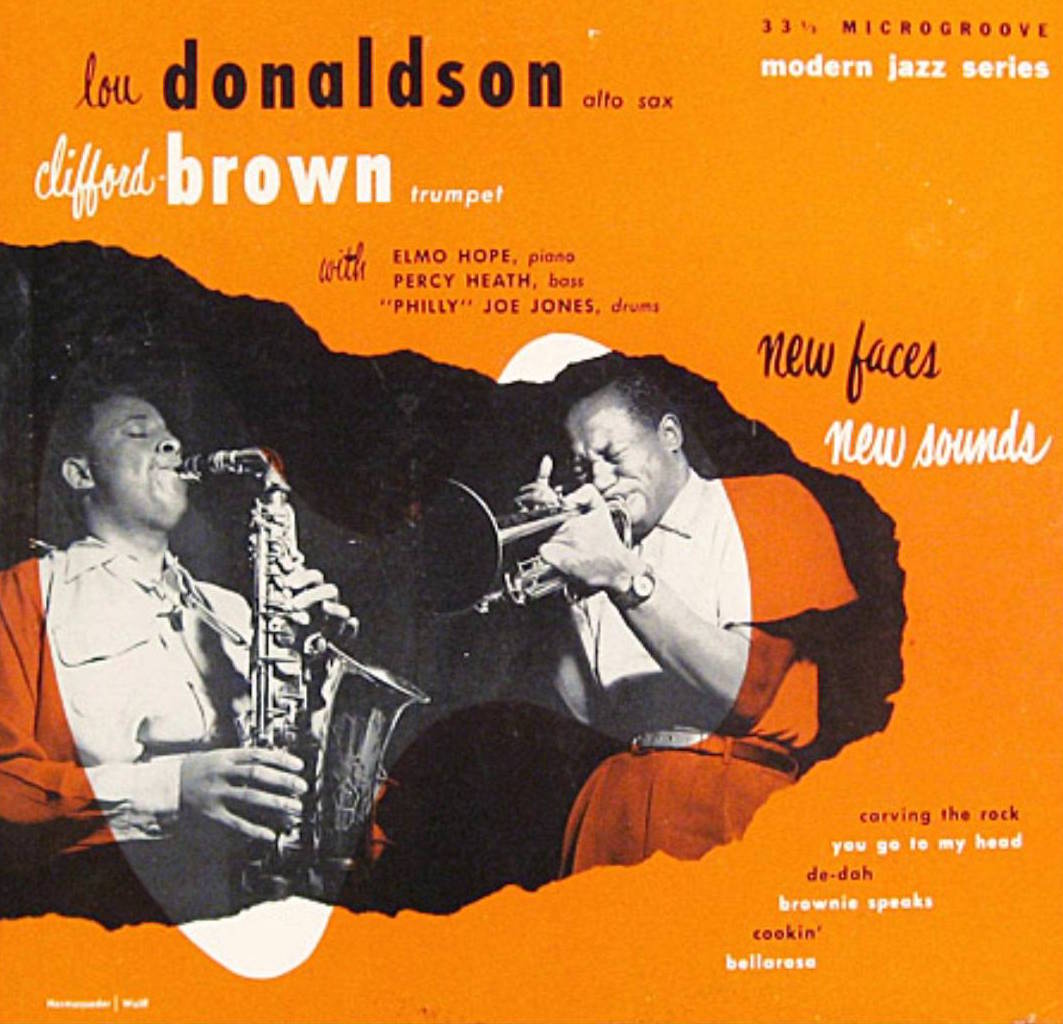

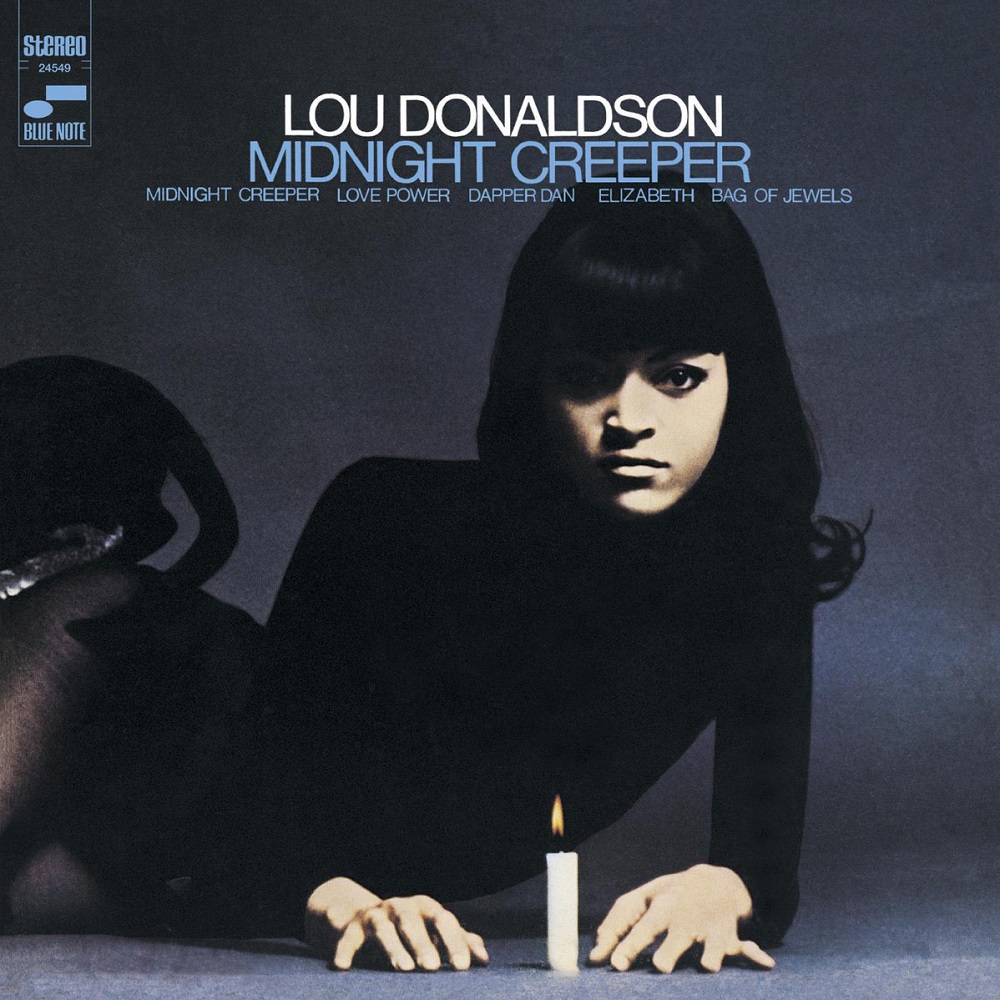

Lou Donaldson quickly latched on to the Varitone. He played it on some of his popular jazz funk records with organists Charles Earland and Lonnie Smith and drummer Idris Muhammad. Donaldson used it sparingly, focusing on his tone, all silk and velvet and satin. Listen to Turtle Walk from Hot Dog and Everything I Play Gonna Be Funky from Everything I Play Is Funky.

On his only association with the Varitone attachment, Rusty Bryant pulled out all the stops on Night Train Now!, 1969 jazz funk affair with Jimmy Carter on organ, Boogaloo Joe Jones on guitar, Eddie Mathias on bass and Bernard Purdie on drums. Heavy artillery. Buzzing like a bee, howling like a bear, Bryant hits Cootie Boogaloo and John Patton’s Funky Mama right out of the ballpark.

Why did Stitt or the others did not extend their experiments with the Varitone and CMA in the ‘70s and beyond? Perhaps they eventually preferred the authenticity of acoustic sound over the ‘clumsy’ Varitone. Or maybe they felt constrained by the endorsements of the devices. I coincidentally heard just yesterday from my jazz friend Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven, who was friendly with Sonny Stitt, that Stitt hated the Varitone, which contrasts with his enthusiastic Downbeat comments.

Why did fusion artists did not pick up on the electric attachments? Most likely, before anyone cared to try, synthesizers provided all the sounds one could wish for. Or am I missing something?

Possibly. Immersed in the heavy sounds of these hot cats.