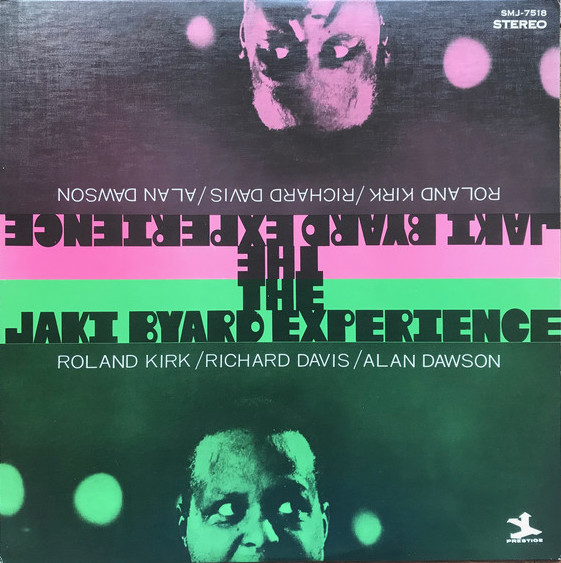

The Jaki Byard Experience is not for the faint-hearted.

Personnel

Jaki Byard (piano), Roland Kirk (tenor saxophone, clarinet, manzello), Richard Davis (bass), Alan Dawson (drums)

Recorded

on September 17, 1968 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7615 in 1969

Track listing

Side A:

Parisian Thoroughfare

Hazy Eve

Shine On Me

Side B:

Evidence

Memories Of You

Teach Me Tonight

No doubt, those that long for the continuous flow of the sounds of surprise go to Jaki Byard and Roland Kirk. In particular The Jaki Byard Experience, which most likely brings about shock, curiosity, delight and finally surrender. Two distinctly unconventional individuals for the price of one. The quartet of Byard’s eleventh album on Prestige is completed by bassist Richard Davis and drummer Alan Dawson, a sublime duo that bonded with Byard for the first time in 1963 and whose instincts are cooperative instead of merely supportive.

Although active in the Boston area since the late 40s, Byard made his mark in New York with Charles Mingus in the early 60’s, dazzling listeners and audiences with his eclectic style. Kirk burst on the same scene around that time; blind one-man-band playing tenor sax and exotic saxes that he found in shops like the stritch and manzello, adding whistles that hung on his chest, shoulder, hip or even ear, appearing to be a sideshow attraction to the general audience, a musician with exceptional declarations of independence to cogniscenti and colleagues.

Both shared the gift of mining the multi-faceted tradition and simultaneously pushing it to its outer limits, both were unique personalities that refused to take indiscriminately the innovations of Ornette Coleman, playing a kind of hide and seek with avant-garde instead of merely engaging in ersatz Free Jazz. Byard’s encyclopedic knowledge of early jazz forms is legendary. Kirk, who also landed a place in Charles Mingus’s band in the early 60’s, mixed blues with modernity and unusual virtuosity. Their music is a world unto its own. And it brims with enthusiasm. Like Thelonious Monk’s music.

An improviser should work with the fixed material in a piece to avoid hackneyed phrases.

That’s Monk, the Buddha of jazz, occasionally breaking silence with conceptions that are at once practical and enigmatic. Paradoxically, what seems to be a knockdown argument led him down the path of “rooted freedom” as opposed to freedom for freedom’s sake. Freedom for freedom’s sake is a dead end street. Free love is ok but mostly equates with detachement. The opportunities inherent to mass consumption suck: fast food and sugar are killers. Both conceptions ultimately exhaust themselves in the need to preserve meaning. The equilibrium of passion and reason cannot blossom in the absence of transcendence. Monk may have been a puzzling personality but he most likely had rooted freedom on his mind while teaching beautiful and original alternate chords to friends and journeymen, and writing Trinkle Tinkle and Criss Cross.

And Byard and Kirk understood. As a result, one gets served a dish of delicious music that while worked out within the textures of harmony and melody, sends mysterious scents out the backyard into the alley and teases the palate with an abundance of spicy flavors; implicit loyalty to unpredictability and deeds of gutsy passion that keeps any negative sensation of self-consciousness out the door.

One gets a rebellious version of Bud Powell’s Parisian Thoroughfare, which is introduced by a turbulent intro in the root key, segues crisply into the theme and is developed with the thunderous blasts of Kirk’s solo’s on, respectively, manzello and tenor saxophone. Manzello Kirk is a scudding jaguar. Tenor Kirk is the leader of the buffalo tribe, deceptively light on his feet and howling with fatherly authority. On both instruments, Kirk’s sense of old-fashioned swing is palpable and his timing is angular and agile throughout his long story, which ends with a roar on simultaneously played horns.

Byard throws himself into battle with hammering bass notes, shrewd combinations of distorted chords, endless staccato bop motives and a climax of tart Earl Hines-ish embellishments. His rubato interaction with Alan Dawson’s snare rolls is one of the examples of the quartet’s sublime and lively interaction. As is the high energy of bassist Richard Davis. Davis has his share of storytelling, mixing strong arco bass with mischievous dissonance and bended notes on multiple strings. This is jazz that rivals the archetypical rock bands of the late 60’s. Mind you, on acoustic instruments!

It makes sense that Byard included a composition of Monk, himself a master of dedication. Evidence is the session’s second example of controlled mayhem. Perhaps the curious balancing act of Kirk, a rollercoaster ride of phrases that are wrenched from his gut and purposefully evade the changes, may be hard to digest. Regardless, it is a rare feat. Kirk apparently only takes a breath twice. Cat with the lungs of a whale.

One gets the hefty boogaloo treatment of the traditional Shine On Me, romantic and sardonic piano-bass duet of Hazy Eve, twisted Fats Waller homage of Memories Of You. Coasting is absent in Byard’s case. He’s the guy that wears haute couture on top and shorts beneath, strollin’ on the snow-bound path. Kirk’s the man on the barstool whom everyone tells his stories too. And he’ll remark: “Never end your sentences on a vowel.” They are the proud underdog. One wonders if Byard’s recorded vocal that precedes the opening of Parisian Thoroughfare and the record – “Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud” – is pride or pastiche.

Definitely the things they’re saying so loud are of the utmost excitement and authority.