Ruud Breuls, sideman par excellence and trumpeter in the renowned German WDR Big Band, lives and breathes straightforward modern jazz, with a particular passion for Freddie Hubbard. “Hard bop is the ideal canvas for my sound.”

Afoggy day in Amsterdam town. The Muziekgebouw Aan ’t IJ is empty, our voices richochet off the walls like the sounds of wild animals inside a hollow oak tree. Familiar terrain for Breuls, who among many other endeavors, starred as a soloist in

Shades Of Brown, a tribute to Clifford Brown by the Metropole Orchestra. Breuls, a slender, tall man dressed in a classy woolen overcoat, the soft-hued southern Limburg accent still intact after years in central Holland, enthusiastically peers into the layers of mist that hover over the IJ River. He says, with the sense of wonder typical of his region of birth, where lady chapels are an equally common sight along the roads than traffic signs: “I’ve got my camera with me, you never know. A bit of sun might peek through the fog. That’s beautiful, almost mystical…”

Also very ‘Limburg’: the marching band. “Yes, I grew up with marching bands. They really meant business! It was my initiation into music, but hardly a defining moment. What is? You know, laying out a career path only explains the musician on a superficial level. A defining moment runs deeper. It’s about atmosphere, feeling. More than the fanfare, LP’s fundamentally brought about a change. My brothers came home with records, I loved hard rock, Deep Purple, Black Sabbath. Then there was that Brecker Brothers album, Heavy Metal Be-Bop. Wow! Weird! That cover with the helmet and trumpet, fascinating. They were funky and improvising, which was still a mystery to me. However, the first real defining moment was a Count Basie compilation album. Including Thad Jones and Snooky Young. Oh, Jezus, what is this?! Well, it was swing, of course. A seed was sown.”

The seed, eventually, carried the young, humble Southerner around the country and the globe in a varied assembly of outfits. While specialising in the classic hard bop quintet formation, co-leading hard-swinging groups like Buddies In Soul with veteran pianist Cees Slinger and saxophonist Simon Rigter onwards from the early nineties, Breuls’ career as an orchestral player flourished. Breuls played in the Metropole Orchestra, Dutch Jazz Orchestra and Jazz Orchestra Of The Concertgebouw. Simultaneously, the trumpeter worked in popular music genres, performing and recording with national celebrities like Marco Borsato, Andre Hazes and Gordon, notably with The Stylus Horns, as well as international artists like Seal and Nathalie Cole. Revealing a healthy dose of self-mockery, Breuls assesses his current, declining amount of commercial jobs. “I’m too busy. But honestly, the wrinkles of middle age do not really fit the commercial profile as well anymore. However, they’re perfect for a jazz man!”

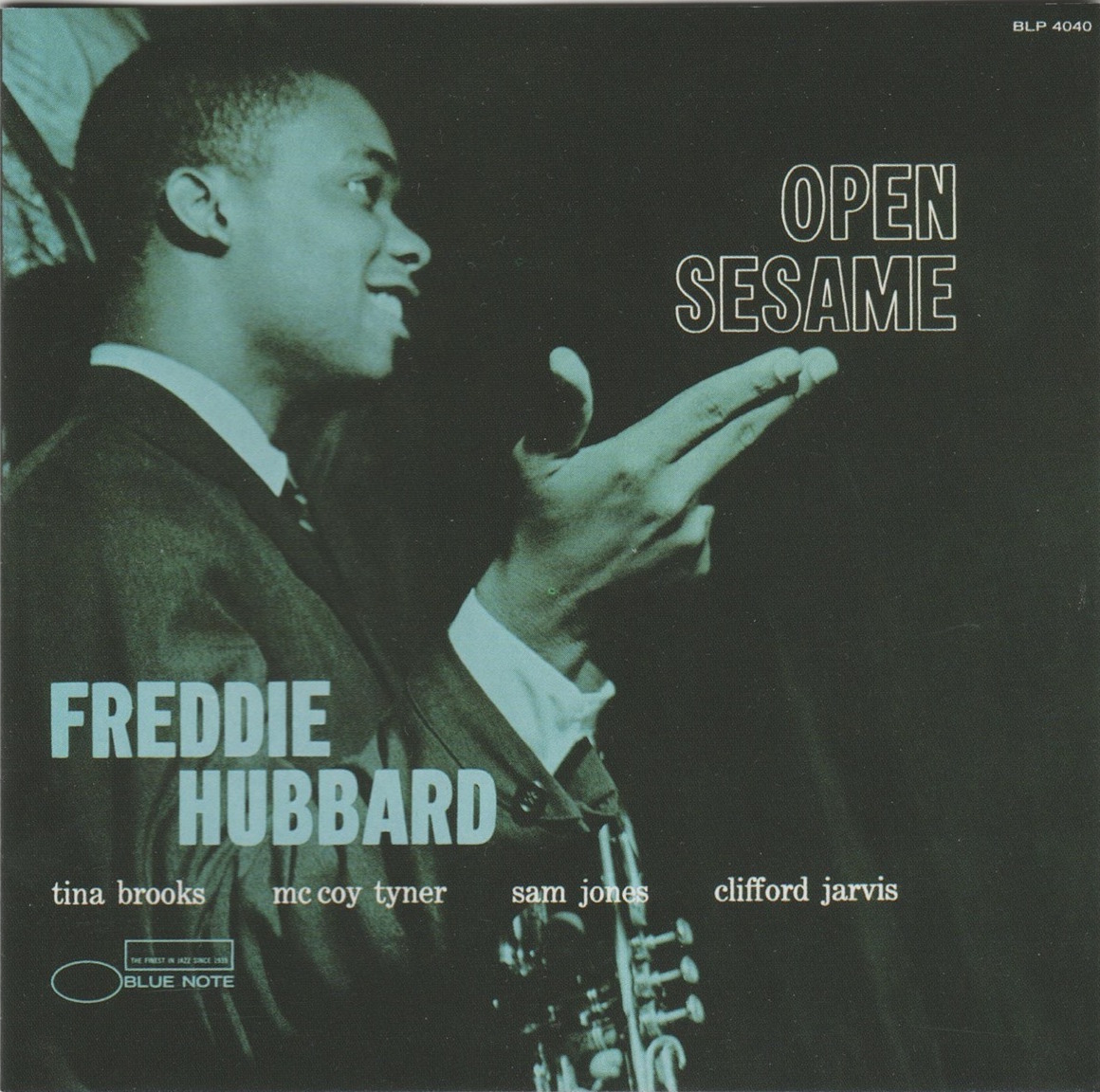

For Breuls, his other major defining moment was the discovery of trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. “It was life-changing. To this day, Hubbard is the reference for my style. He’s my main man, Freddie’s in my heart, from the day I bought a Blue Note twofer LP in Rotterdam at age nineteen. It contained Here To Stay, Ready For Freddie, Goin’ Up and Hup Cap, I think. I was stunned! The way Hubbard sculpted his lines and coloured his phrases and bent his notes. The flow of ideas, the swing and that bright sound. That was it. Basically, the Hubbard style of the early sixties defines the way I play. The way I would like to play.”

“There were others, of course. I learned that Miles Davis was the chief god, the genius of the use of space. An unforgettable identity. There’s Lee Morgan, the funky master. I really admire his bravura. It’s delivery time: here’s Lee! The way Morgan forges himself through those changes on Coltrane’s Blue Train album, you know, in Lazy Bird, is a gas. You should write out those lines, frame and put them up on the wall, they’re so beautiful. There are musician’s musicians like Kenny Dorham, Woody Shaw. Outstanding. And there’s Clifford Brown, of course. Brilliant in all registers and what a sound. Although I’m versed in bebop as well, when I did that Clifford Brown performance, I was glad we concentrated mainly on ballads instead of the faster bop tunes!”

“Sound is the identity of the musician. Some trumpeters use a lot of air. That’s beautiful. But I just can’t. A straightahead, round and open tone comes natural to me. It’s allowed to shine and shimmer. I’m white, not black. In a sense, my style is tongue-in-cheek. The sound is clean, pure, would almost fit in a symphony orchestra. But what I play is unadulterated jazz, obviously.”

The passion for straightforward jazz is shared with a coterie of musicians, notably drummers. “It really is hard to explain, borders on telepathy. Like the drummers of the classic hard bop era, guys like Eric Ineke, John Engels, Cees Kranenburg, and including free bird Han Bennink, are, for all their supurb skills, propulsive groove-masters first and foremost. The American drummer Adam Nussbaum as well. And they’re unique in listening to the soloist, stimulating him instead of dominating the proceedings. They have an in-built sense of the phraseology and rhythm of the classic horn players and recognize all the quotes, more so than myself! Eric Ineke especially, he’s liable to lay you down on the barbecue! A shout here and there. That’s a party! It’s a primitive, jungle feeling, jazz in its purest form. From the contemporary trumpeters and jazz musicians, I really regard Roy Hargrove as a hero. A perfect synthesis of hardbop and bebop. Most of all, he’s such an honest musician.”

Pure jazz has a hard time. “We’re a minority in The Netherlands. It’s not hip, supposedly not innovative enough. Which is weird and really irritating. My beloved hard bop, and the tradition and bebop as well of course, make up the fountainhead of jazz. It really is a good development that many young guys are into odd meters and have non-jazz influences. But ideally, those influences would be the icing on their real jazz cake. But all too often the real jazz is left out in the cold. But when played well, hard bop is fresh as a spring leaf. As busy as I am, I try to do at least two or three quintet gigs a month now, with my old pal Simon Rigter for instance. The quintet format is essential for my well-being! I would really like to do more of this stuff again, to be honest. I did a little tour with saxophonist Benjamin Herman and John Engels a couple of years ago. That was great. Benjamin and me are on the same wavelength. I would love to get together again.”

As tall and marked by more than a half decade of life experience on this globe we sometimes call the Big Bad Apple the 54-year old Breuls may be, occasionally seasoning his anecdotes with a fervent four-letter word, there’s a spark of a young boy inside. A sensitive kid who has a hard time fitting in with the hardliners on the schoolyard. One to cherish, soothe. Something in the personality of Breuls is tender, fragile. The carefully crafted style and crystalline sound of Breuls symbolize part of that innocence, suggest a longing for the angels to speak up. His sensitivity, Breuls contemplates, is the reason behind the trumpeter’s life as a sideman. “Those are deep waters. Essentially, it has to do with my family history. Basically, my confidence level is low. The trumpet is a challenge to deal with that. My role as a sideman, as opposed to a leader, is a logical extension of my personality. Besides,”, Breuls chuckles, “I was asked for everything I’ve done, you know.”

“I did a lot of gigs with Michiel Borstlap. He was very stimulating, really pushed me to the front. Figuratively, but also quite literally! Michiel is a very compassionate human being. We share a love for Hubbard, and Herbie Hancock as well. I liked to play fusion, occasionally. So, I was quite upfront there with Michiel, in spite of myself. As ‘Miles’ with the Metropole (Breuls was the leading soloist during integral performances of Porgy & Bess and Miles Ahead, among others, FM) and Clifford Brown, I was in the limelight as well, of course. It was a real good feeling to get under the skin of those giants. As an effect, I really pushed my envelope, playing better day after day. At any rate, the seat in the WDR chair really suits me to a T. The alternation of playing the parts and solo spots is wonderful.”

The volume of Breuls’ voice is turned up a notch or two. “Aaah… The WDR Big Band is really something. One hell of a big band! An interesting international cast. The gutsy delivery of the WDR Big Band floors me completely. And the variety of guest stars is striking. Since I’m in the band, we’ve had Jimmy Heath, Ron Carter, Billy Hart, Al Foster, Dick Oatts, Chris Potter, Antonio Sanchez, Ambrose Akinmusire… I really dig my role in the sound spectrum and relish the solo spots. I’m like that little devil jumping out of the box. Everybody is on their toes and we’re really stimulated to be greasy, to scrape off the layer of varnish. The WDR has a hard-boiled attitude: give us the fucking juice, man! Come on! You wanna be a jazz player?! You know what I mean?”

One wouldn’t be surprised if that band will account for defining moment number 3 in the life and career of Ruud Breuls. “Who knows? Time will tell. Those things really have to be left to fate.”

Ruud Breuls

Ruud Breuls (Urmond, 1962) is featured on more than 300 albums, both jazz and popular music. Since the early nineties, Breuls has been part of big bands such as the Dutch Jazz Orchestra, Metropole Orchestra, Cubop City Big Band and the Jazz Orchestra Of The Concertgebouw. He currently is a member of the WDR Big Band. Breuls has also been active in long-term, small ensembles such as Buddies In Soul and Major League. The trumpeter performed and recorded with, among others, Kenny Barron, The Beets Brothers, Bob Brookmeyer, Billy Cobham, Michiel Borstlap, Ronnie Cuber, John Engels, Billy Hart, Jimmy Heath, Benjamin Herman, Bill Holman, Eric Ineke, Joe Lovano, Vince Mendoza, Michel Portal and Mike Stern. Breuls teaches at the Conservatory Of Amsterdam. In 2013, Breuls won the Laren Jazz Award. In the Spring of 2017, a Louis Armstrong project of Breuls and Simon Rigter will be released by Sound Liaison on CD and made available as high-resolution downloads.

Photograph of Ruud Breuls above by Mattis Cederberg; on the homepage by Robert Roozenbeek Photography.