Dominique Jennings Brandon fondly remembers her father, the artist Richard Slater Jennings, a.k.a. “Prophet”, known among jazz fans for the sleeve artwork of Eric Dolphy’s Out There. In our e-mail interview, she speaks candidly and in great detail about the colorful and heady life and work of the painter, journalist, filmmaker, hustler and spiritual ‘consigliere’ to many of the modern jazz giants.

Arebellious, wordly spirit who usually was exactly where it was at in the classic jazz era of the fifties and sixties, the highly esteemed Prophet befriended the cream of the modern jazz crop. Legends like Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Freddie Hubbard, James Moody, Jimmy Heath, Slide Hampton and Johnny Griffin were pals of Prophet, who shared both their heartfelt passion for America’s truly original art form as well as the arduous and proto-rock&roll lifestyle attached to it. In appreciation of his friendship and personality, both Eric Dolphy (The Prophet) and Freddie Hubbard (Prophet Jennings) dedicated compositions to Richard “Prophet” Jennings.According to legend, Jennings treated musician King Porter to an inexhaustable string of anecdotes about cons and tricks, whereupon King Porter replied caustically, ‘Man, you a motherfuckin’ prophet.’ The name stuck. Prophet liked to tell a story. There’s a telling example in John Szwed’s biography of Miles Davis, So What):

“I remember one night, one time, Max Roach and Clifford Brown… They were playing at a club in Detroit – The Crystal Lounge. So this particular night we’re at the Crystal Lounge and Max Roach and him had set the stage on fire. Now, Miles, he was – you know, he was staying around Detroit at this time. It was raining like a motherfucker, so this particular night, Brownie had just come off the stage. That stage was a burning inferno. Clifford Brown had set that motherfucker on fire… The door opened and in walked Miles. He had his coat turned up and it was raining… He went over to Clifford Brown and asked for Clifford’s trumpet. He reached in his inside pocket, took out his mouthpiece, put it in Clifford’s trumpet… Now, the stage was still on fire. It was still burning… Miles got up on that stand with the support of the piano to hold his ass up. He put that motherfucking trumpet to his mouth and that motherfucker played My Funny Valentine. Clifford Brown stood up there and looked at him and just shook his head… That little black motherfucker, behind all that fire, he made people cry… When he got through playing and took his mouthpiece out, he put it back in his coat, gave Brownie his trumpet, and split. That’s what he did. I saw this. I was there!”

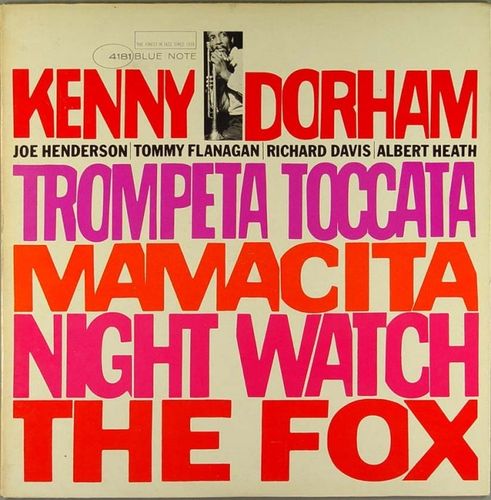

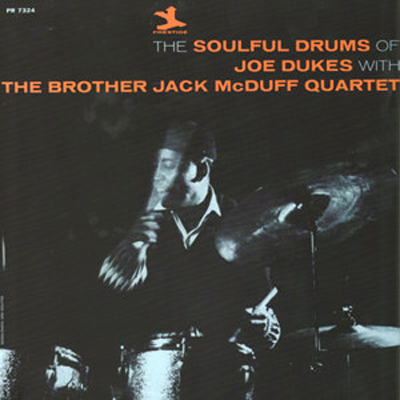

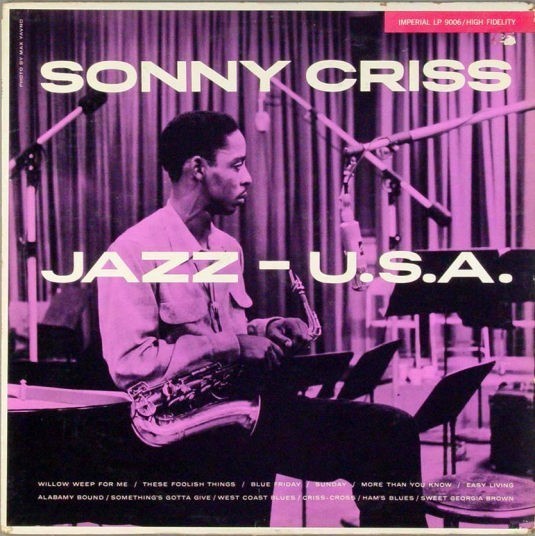

A couple of years later, Thelonious Monk visited an exhibition of paintings by Prophet in Detroit, which resulted in Prophet’s portrait of Monk for the Jazzland album Thelonious Monk With John Coltrane. Prophet also designed Max Roach’ It’s Time. His best known covers are the Dolphy albums Outward Bound and Out There. I’m sure most of you shared my puzzlement and curiosity when stumbling upon Out There as a teenage jazz fan, a cover that conveys a Dali-esque space landscape including a cello (or upright bass) battleship and giant-size metronome. Prophet’s album covers are significant for being among the first that were designed by Afro-American artists. Instead of focusing rigidly on a marketable image, Prophet strived to evoke the mood of the adventurous music contained within the grooves.

Bits of information reveal that, allegedly, Prophet danced around the steelmills of Youngstown, Ohio as a kid; that he worked as a (music) journalist in Detroit. Prophet’s work as a painter, instilled with the spirit of the Harlem Rennaisance, was exhibited in the US from the mid-fifties onwards. He settled in Sweden in 1964 with his future wife, the Swedish air line hostess and former singer Ann-Charlotte. His paintings were exhibited in the US and Europe. Prophet suffered from tuberculosis in his younger life. Tragedy befell the artist and his daughter when Ann-Charlotte, mother of the then four years old Dominique, died in a plane crash in 1969. Prophet returned to the US and worked in comedy with his friend Richard Pryor, among other creative endeavors. Prophet passed away in California, in 2005.

In 2001, director and film writer Ken Goldstein made a documentary about Prophet, Prophet Speaks, which included footage of the days and nights the artist spent with Rollins, Gillespie, Coltrane, Monk, Davis et al. Unfortunately, it wasn’t released on dvd. Most admirers of jazz and the arts, therefore, have remained ignorant of the life of a pivotal underground artist and jazz guru of the fifties, sixties and beyond.

Flophouse Magazine: Where and when was your father born?

Dominique Jennings Brandon: He was born Richard Slater Jennings on April 5th in Youngstown Ohio in the mid-20’s.

FM: There’s a story about your dad about him dancing around the steel mills of Youngstown, Ohio as a kid. Is that true? In a vaudeville show, or on his own?

DJB: He danced around Ohio mainly on his own. The WLW was a big Nightclub, as well as Eddie’s. He danced with Billy Hicks and the Sizzling Six Review. He went on the road with them. He also was a dance show promoter.

FM: He lived in Detroit in times and circumstances that were often quite difficult for Afro-Americans. How did he get by? And how did he become an artist?

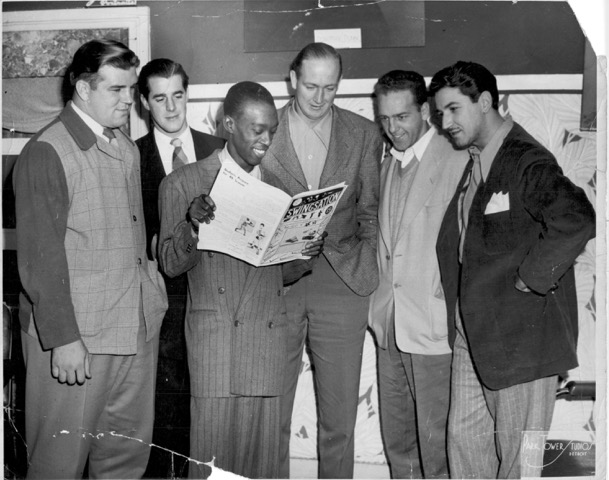

DJB: Lionel Hampton read an article Prophet wrote about him for the Buckeye Review and came to Youngstown looking for him. Prophet became Theatrical Editor for the Detroit Tribune newspaper that was owned by Lionel Hampton. He helped raise the circulation. He branched out with his partner Kenneth Brown to start their own Magazine called “Swingsation”. And then there was one issue of a paper called “The Word”. He was asked to be Advanced Publicity Man for Lionel Hampton’s Band. So he went on the road with Hamp and his band. Hadn’t been making much money. During his time in Detroit he became known for his good conversation and good weed, “Chicago Light Green”. He was a Healer and Confidence Man. He was living at the YMCA for a time which was $7 a week but difficult to cough up. He ran the concession bar at the Flame Showbar. That is how he met a lot of musicians.

He had a second bout of tuberculosis in the late forties and was hospitalised. It was during his 15-month convalescence that he took up drawing. He was always gifted at drawing and his friendly, treating doctor Dr. Greenich gave him a set of Pastel Chalks. He was discharged in 1950. He graduated from Chalks to oils when he bought a stolen set of oils paints from a known junkie in the neighborhood.

FM: “Prophet”, as your father was called, has also been a journalist and filmmaker. But he is mostly known as a painter. What do you feel is his lasting contribution to the world of arts?

DJB: His unique life poured into his work, which cemented an unseen perspective in art during the post-Harlem Renaissance period. He brings a raw emotional depth to his painings which spans many subject matters over the decades. Being a self-taught artist who was inspired by the Masters added more depth to his work. His portraits have eyes that follow you. His approach to painting skin is luminescent. His command of oils is uncanny and his early Pastel Chalk pieces are lush. His dimension, depth, perspective, and lighting are reminiscent of a much earlier era. His ability to capture such intimate moments on film with the modern jazz giants was another layer of his artistry. I think his ear and eye for greatness only intensifies his gifts and contributions to the art world.

FM: Has he worked in comedy? He was friends with Richard Pryor and Redd Fox, right?

DJB: He had a potent sense of humor and was a fantastic storyteller, which came from a rich life experience. He met Redd Foxx during his time in Detroit and Richard Pryor in New York in the late sixties. He worked as a consultant on the Richard Pryor Show in 1977 and was quite inspirational in the comedy circles. He is referenced in the Richard Pryor documentary “Omit the Logic”. Richard Pryor hosted an art show for him in Los Angeles in 1975.

FM: Your father was friends with many of the modern jazz legends, like Freddie Hubbard, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk, Johnny Griffin, Slide Hampton. Why do you think those jazzmen gravitated towards your dad?

DJB: His gravitas was undeniable. I believe they were all kindred spirits. Tastemakers. Together they were the integral part of an elite subculture. And the music they loved was the heartbeat. He provided them with a lively space to let their hair down. They called Prophet’s apartment the “Temple”. They were creative entities that fed off of each other. He enjoyed talking with his musician friends because they talked about everything. Not just music. Politics, religion, philosophy and everything in between. He was outspoken, blunt, no nonsense, witty, stylish, charming, compassionate, encouraging, generous and wise. The antithesis of a yes man. Widely talented, loyal and the ladies were quite fond of him!

(Left: Albert “Tootie” Heath, Actor Lee Weaver, Prophet Jennings, Jeb Patton and Jimmie Heath at Jazz Bakery, Culver City, late 90s; Right: Prophet and Richard Pryor)FM: Do you have recollections of meeting his musician friends in Sweden and the USA?

DJB: I was too young to remember any specific encounters with the musicians in Sweden. When we lived in the Los Angeles/West Hollywood, I remember Dizzy Gillespie visiting us and we went to his performance at the Hollywood Bowl. He also gave my Father a movie camera. I remember encountering Miles Davis driving in our neighborhood when he invited us to join him at a fancy clothing store for a shopping excursion. His ex-wife Francis Davis was a longtime neighbor of ours who lived on the same street. Tootie Heath was close to my Father. He was my Father’s best man at his wedding in Sweden. Jimmy Heath remained close even though he was on the East Coast. They were both basketball fans. I remember Yusef Lateef coming by and my Father filming him.

Most of his earlier musician friends remained on the East Coast as we were on the West Coast. I did see Marvin Gaye with my father about 8 months before he was killed at a party. I was starstruck by him. He told me he met me in Sweden when I was a little girl.

I met a lot of his friends later in life, generous men like Freddie Hubbard, James Moody and Gerald Wilson. My husband took me to see one of Freddie Hubbard’s last performances at the Catalina Bar and Grill. There was a request for him to play Prophet Jennings but he was unable to play because of the wind it required.

FM: In the fifties, your father was an integral part of the outsider movement of jazz and the arts that turned out to be very influential and he has always lived a very bohemian lifestyle. How was it to grow up with Prophet?

DJB: There was a Bon Voyage party in New York for my Mother and Father when they were moving to Sweden in 1964. They were in love and he had grown weary during the turbulent sixties in New York. My Mother Ann-Charlotte (née Dahlqvist) or Lotta, was a air line hostess for SAS and had sung in a swing band in the fifties. They moved to Sweden in 1964, right after the party. We lived in Sweden and my Mother and Father were instrumental in helping to get their jazz musician friends booked at the Golden Circle. My Father made treks to the States to sell and exhibit his work. At times he loathed the cold and darkness of Sweden and longed for New York. Life wasn’t always easy, especially having to raise a little girl but they made it work. They were a real team. A tragedy that would forever change and completely devastate my Father happened on January 13, 1969, when a plane crashed with my Mother in it. My Father and I were splattered on the covers of Swedish newspapers after the crash. It is still quite hard to look at the clippings.

My Father and I left Sweden in 1972 and moved to West Hollywood. We even had a short stay with Richard Pryor when we first arrived. He continued to paint through the 70’s and 80’s and 90’s. He never remarried. He taught himself how to do astrological charts in the sixties. I still have many of his very detailed charts. He was quite gifted in this area as well and was able to hone in areas that were hidden to most. I encountered several instances where his predictions were stunning. He was a life coach, confidant and astrologer to many people throughout his long West Hollywood residency. Especially during the last ten years of his life. Chaka Khan lived in our apartment complex when she sang with Rufus. She and my father were both Aries and had a fondness for each other.

My Father was utterly devoted to raising me and being a widower and artist could not have been easy. He was very particular when it came to babysitting. He was completely hands on. He was a deft cook, so funny and an extremely deep thinker. In fact we rarely ate meals out. He was quite temperamental at times, which being a sensitive young girl I did not quite understand. I took his impatience to heart but understand so much more now. He was so concerned about being a good parent. The realities of life were not “sugarcoated” for me. He believed in giving it to you straight.

I do not know how we made it but I was always made to feel like a Princess and he encouraged me in my endeavors. I never wanted to disappoint him, which was quite a big weight I put on myself. His candor could bring me to tears but I understand now how fortunate I was to have him so invested. He was a huge inspiration to me and helped shape my love for the arts. He always told me to keep an air of mystery about myself and educated me about the male species. He was a stickler about having good credit and instilled in me that you should try to accomplish something everyday. No matter how small. Even when I moved I lived under a mile away. We spent a lot of time together and as I got older we became even closer. I began to realize a bit late that I could discuss things with him I never thought I could when I was younger. He expressed to me “you sure are cool Pistol” towards the end of his life. Pistol was one of my many nicknames.

(Left: Prophet and Dominique, Jet Magazine 1970)My Father contracted pneumonia in 2000. We were able to get him to Cedars Sinai after an episode at his apartment. Richard Pryor passed on December 11, 2005. It was a huge blow to my Father. That week he wasn’t feeling well. I attended Richard’s funeral and when I was asked where my Father was, I responded that he wasn’t feeling good. I will never forget the comment that was uttered. “Is Prophet next”? My Father passed the next day. Exactly one week apart from Richard Pryor.

FM: Your father was one of the first Afro-American artists that designed covers for jazz records. Was it something he took particular pride in?

DJB: He did take great pride in the album covers. It was something that came about quite fluidly. He did not seek out work as an album cover artist. He felt it a huge honor to have songs and whole sides of albums dedicated to him.

FM: His work for Dolphy is surrealistic. He painted in other styles as well, right?

DJB: He did paint in many genres. He didn’t subscribe to any style per se. When he started to paint in Detroit he was painting in Pastel Chalks about the life he saw: The “Underworld”, “Drugs”, “The Jazz Life” “The Streets”. Some of his work had an erotic and mystical sense. He was drawn to painting streetscenes, cityscapes, nudes, children, flowers, old people. He was first inspired to paint by an artist in Ohio called “Dollhead”. He admired Rembrandt, especially his extraordinary lighting, and Dali. When he arrived in Detroit he learned about more of the Masters. His inspirations became Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, Modigliani and Maurice Utrillo.

FM: I read that the walls of Sonny Rollins’ apartment were decorated with the paintings of your father. And Cannonball Adderley exhibited them in his home. There were exhibitions in the US and in Europe of his work. But where is his work now?

DJB: That is the big question, where is all the work?

My family and I have about eighteen works. Over the years I’ve been doing my best to catalogue his work. So there are paintings spread throughout Los Angeles. Jennifer Pryor (Richard Pryor’s widow) has the large Charlie Parker painting mentioned in the documentary “Omit the Logic”. Berry Gordy, Jimmy Heath, my father’s friend and former journalist Joy Brown and our old neighbors all own paintings. Milt Jackson’s widow owns the portrait of her late husband that he painted in 1960. The latest painting resurfaced a few years ago, when the wife of the late Prestige Records Founder, Bob Weinstock, contacted me on Facebook. She has the painting of Eric Dolphy used for Outward Bound. This was fantastic news.

I have put feelers out to a few other people who I know have paintings requesting photos. My Father had contracts that I have and use to connect the dots but there were many paintings that he did not have contracts for. I once asked my Father how many paintings did he paint altogether and he answered, “I don’t know”. I told him my dream was to find them all and he told me I wouldn’t be able to do it. We’ll see! A multimedia retrospective is the goal.

Dominique Jennings Brandon

Dominique Jennings Brandon (Stockholm, Sweden, 1965) is an actress who is best known for her role as Virginia Harrison in NBC’s soap opera Sunset Beach. Jennings Brandon’s resume includes Se7en and Die Hard 2. She lives in San Gabriel, California.