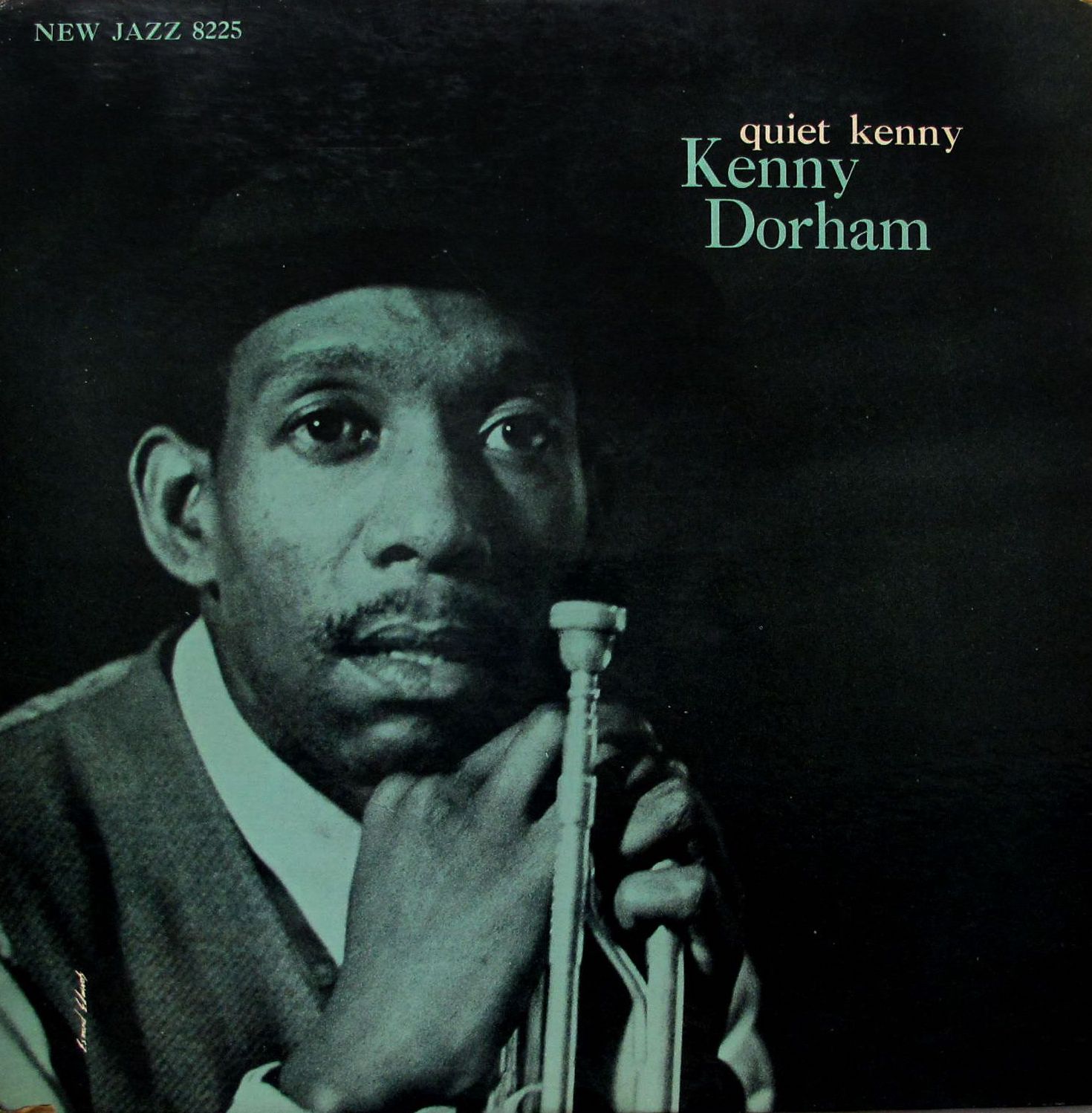

Less is more on Kenny Dorham’s Quiet Kenny, more or less the trumpeter’s most beautiful record as a leader.

Personnel

Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Tommy Flanagan (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), Art Taylor (drums)

Recorded

on November 13, 1959 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as NJ 8225 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Lotus Blossom

My Ideal

Blue Friday

Side B:

Alone Together

Blue Spring Shuffle

I Had The Craziest Dream

Old Folks

An anecdote that Rein de Graaff once told me concerned his first ever visit to New York City in 1967. The first thing that the burgeoning Dutch pianist and hard bop aficionado noticed when he stepped out of the subway station in the East Village was a fellow with a trumpet case that was the spitting image of Kenny Dorham. As a matter of fact, after politely inquiring, it turned out to be the one and only Kenny Dorham. Dorham invited the dumbfounded De Graaff to a gig the following night. The rest is history in the case of De Graaff, who stepped into a dream and subsequently met and played with Dorham, Hank Mobley, Barry Harris, Paul Chambers and Billy Higgins. Nice career boost.

Most people would not have recognized Dorham, one of the great modern trumpeters of a form of art whose geniuses like Parker and Monk eluded mass recognition for so long, let alone superb disciples as Kenny Dorham. Dorham is part of a great pack whose members were dubbed ‘musician’s musician’, which signifies esteem from colleagues and critics which equals poverty so must’ve been terminology that left the pack disgusted. Go to hell with your musician’ musician stuff, I need to pay my bloody rent! Dorham was a major league musician’s musician, a BADDASS musician’s musician, one of the iconic musician’s musicians. Too bad for Kenny. At least he was never described as ‘best kept secret’, which also spells disaster and a lavish portion of vomit.

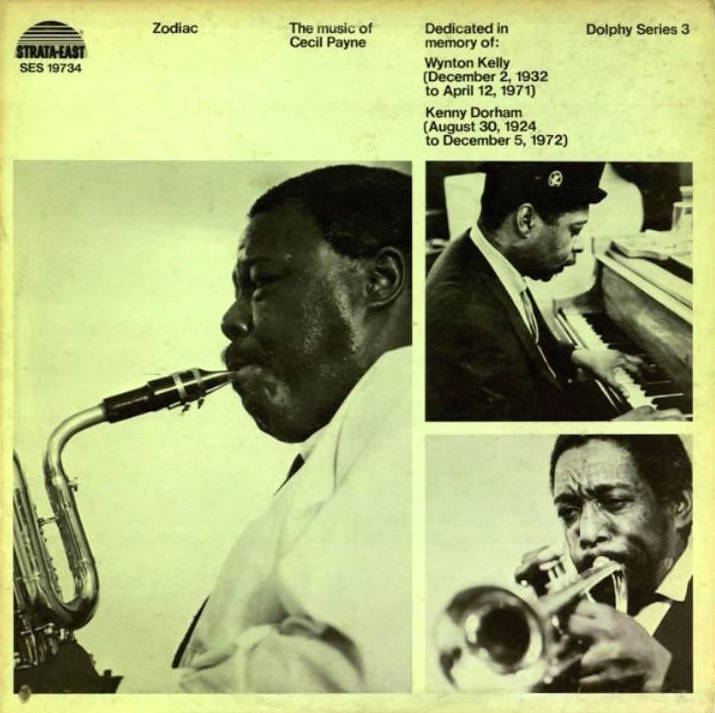

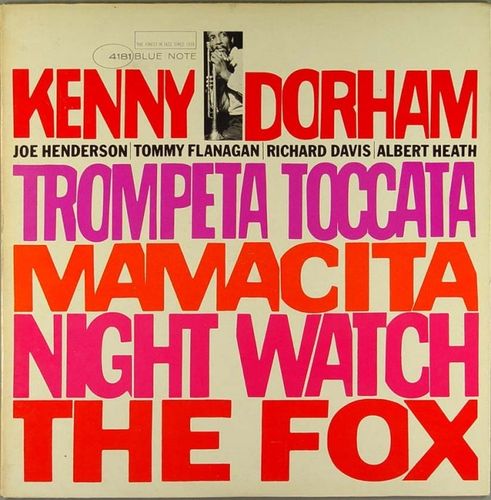

Dorham was active in the bop era, colleague of Parker and Gillespie, a charter member of the first Jazz Messengers incarnation (Art Blakey introduced him nightly as the “the uncrowned king of the trumpet”) and enjoyed a particularly fruitful cooperation with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson in the early ‘60s. Blue Bossa is his best-known composition. His discography is a hard bop playground and Afro-Cuban, Quiet Kenny, Whistle Stop, Round About Midnight At Cafe Bohemia, Una Mas and Trompetta Toccata are essential LP’s. They ooze with Dorham’s tasteful trumpet playing, the opposite of flashy bop, crystal clear weaving of lines anchored by a distinctive balancing act of bittersweetness and sleaze and a tone that I once overheard someone, I forgot whom, describe as ‘sweet-tart’. That it is.

Quiet Kenny is remarkable for the fact that Dorham is the sole horn. Plenty of space for Kenny’s cushion-soft but poignant lyricism. Dorham displays the gift of carrying one to a special zone, where the spine tingles and melancholia is barely suppressed by the bright side of life. Dorham strings together beautifully balanced phrases with apricot, peach and tangerine transformed into sound, all of this flowing on the flexible bedrock of Tommy Flanagan, Paul Chambers and Art Taylor.

All tunes flow with elegance and purposeful movement, whether warhorses like Old Folks or blues-based originals like Blue Friday and Blue Spring Shuffle. Lotus Flower, also known as Asiatic Raes as performed by Sonny Rollins on Newk’s Time in 1957, is an undeniable highlight; a lovely amalgam of the nursery rhyme-ish, Chinese-tinged melody and Dorham’s supple melodic variations. Dorham’s delightful reflection of desire of My Ideal is the other potential poll winner, signifying a trumpeter of compassion and restraint, the latter unique element described in the title as ‘quiet’.

The enjoyment of Quiet Kenny equals eating perfect sushi, savoring every bite of the little Japanese pieces of tuna, seaweed, rice. Dorham is master chef and Mr. Delicate, adding a dash of wasabi here and there. Beautiful record.