Here’s part 2 for you and yours, Alvin Queen talking about his stint with Horace Silver, the European continent of opportunities, the way the legends nudged him to change his style of drumming and the way jazz was and will never be again if something isn’t done about it very soon. “I don’t play any music that the people can’t figure out. They paid and have first priority.”

Temperature is rising and there ain’t no place to go. Beet-red heads nod off in the subway train. Someone put our crotches in the oven. It’s the kind of sticky heat that leads to perennial complaints from the Dutch tribe. Alvin Queen flew over from Geneva to The Netherlands, Rotterdam to be exact. He’s here for the North Sea Jazz Festival and a performance with trumpeter and bandleader Charles Tolliver and the Rotterdam Youth Orchestra. His schedule reads like the itinerary of a foreign minister who is visiting a much-anticipated climate conference and wastes two pairs of shoes in a period of 36 hours. The soles of Mr. Queen’s footwear, not to mention his sticks and brushes, have to endure a lot. There isn’t any time to be wasted. Plane, hotel, rehearsal, hotel, soundcheck, performance, hotel and… plane.

Rehearsal with a capital R. It is scheduled from 2 to 9, which surpasses the 10 to 4 at the Five Spot extravaganzas of the classic era of jazz. An imaginary octet of jazz courts jesters overheard his remark that ‘I never heard of no rehearsal of seven hours’ and add an extra hour of Rehearsal. Tough luck. The immaculate professional takes it in stride. If anything, it’s a jazz family affair. A gift from King Queen to Prince Charles. “I usually don’t play in big bands. I’m not a good reader and have never really liked it. There is no opportunity to be a creative artist. I prefer the spontaneity of small ensembles.”

Alvin Queen is 74 years old, by no means an old-timer but an elder statesman beyond doubt. He’s the same age as some former fusion artists, who also wear the officious label of veterans, but comes from a totally different jazz planet. When fusion and electric jazz reigned supreme in the early 1970’s, Queen, student of mentor Elvin Jones, participant in the gospel scene of Scepter Records and the black organ jazz club circuit, drummer of the Horace Silver and George Benson bands, changed his course. Queen regularly toured in Europe with Charles Tolliver’s original installment of Music Incorporation and rejoined Horace Silver’s quintet. The continent of new opportunities continued to beckon and after a two-year stay in Montréal and many gigs in Europe, Queen settled permanently in Geneva, Switzerland in 1979, “Baby Queen” to the touring elder statesmen of jazz such as Ray Brown, Clark Terry, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and Milt Jackson. The halcyon days.

FM: When you were playing with Horace Silver again in the early and mid-1970’s, what was the repertoire?

AQ: “When you make a hit record, that’s what people want to hear. I was sick of Song Of My Father! Horace said that we had to play it and we sometimes played it two or three times a night. That was the way it went. Miles had to play So What, Coltrane My Favorite Things and Cannonball Adderley Mercy Mercy Mercy by Joe Zawinul. We also played Sēnor Blues and Filthy McNasty. But then Horace changed up and started going into spirituality and recorded the United State Of Mind records. One night I said, ‘Horace, all that Hare Krishna stuff, God, what is going on?’ He said, ‘Alvin, I haven’t changed my music, it’s just the lyrics’.”

(Horace Silver, Michael Brecker, Tom Harrell, AQ, bassist Anthony Jackson not pictured, Philadelphia 1973)

FM: I heard a story that while you were with Horace Silver, you also took care of business for Stan Kenton. Something to do with loose women.

AQ: “That’s right. We were playing the Jazz Showcase in Chicago around the time of In Pursuit Of The Seventh Man. We were staying in the Merlin hotel. Kenton was in the hotel and he had a whole lotta money in his hands. Whores were standing around and keeping an eye on him. I said, ‘Stan, come on, man, put the money away.’ I took him up, put him to bed, kept the money in envelopes. I left him a message to call me in the morning. It was right in time before they would stick him up, haha!”

FM: It tells me you were on the ball and dependable, two things you also need as a drummer.

AQ: That’s right. Apart from swing.

FM: You played a lot in Europe in the 1970’s and eventually settled there permanently in 1979. Why did you decide to go and live in Europe and why Geneva?

AQ: “Well, the American scene was electrified, the music had changed, you had big acts like Weather Report. I had a taste in the early seventies with Charles Tolliver and Stanley Cowell. I met my future wife in Geneva at a party and that is how I managed to stay there eventually. The location was perfect. I could go to France and Germany. I was in the center of things. Important guys like Francy Boland and Pierre Michelot asked for my services. Europe was good to me.”

“I worked with Duke’s bassist, Jimmy Woode in 1972. It’s a funny story. When I was twelve years old, I recorded in New York City. They hired Joe Newman as musical director and he hired Zoot Sims, Hank Jones and Art Davis. Harold Mabern substituted for Hank. I was 12! It was never released. So, when I came to Europe, Jimmy and Joe were arguing about me, Joe saying, ‘I did his record!’. From my association with Jimmy Woode, I ended up with the older generation of musicians, you see. Harry “Sweets” Edison, Clark Terry, Dolo Coker, Lockjaw Davis. At that time, all Count Basie’s men came as individuals to do gigs. A very important thing for me was that I became the house drummer of the festival in Nice in the South of France. You had Oliver Jackson, Gus Johnson, Panama Francis and me. Sometimes, you know, one of them got boozed up and drunk, that was fine because I would play two sets a day and get even more money that way! I played with people like Marian McPartland, Wild Bill Davis, Guy Lafitte, Michel Goudry, George Arvanitas, Michel Saraby and Pierre Boussaguet. I played all over France from then on.”

1984, France

(Jimmy Woode & Harry “Sweets” Edison, Nice 1980s; Ray Brown & Milt Jackson; Charles Tolliver)

FM: A lot of the greats that you played with at that time, Milt Jackson, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Ray Brown, Dexter Gordon, they played with Charlie Parker. Did they talk about Charlie Parker?

AQ: “They always talked about Parker at the dinner table and such. It was between Parker and Billie Holiday. Later on, when I played with Oscar Peterson, he would talk about Billie Holiday all the time.”

FM: How did you got involved with the great Ray Brown?

AQ: He heard a lot about me long before we came into contact, about 15 years before that. Everybody was talkin’, Ray knew about me and he said, ‘Queen, I’m gonna get you someday!’ That was the way it went those days. So, I came to Europe and needed work. Jimmy Woode spread the news, ‘I saw this kid, he can play…’ Ray and I would bypass each other all the time. I was playing with Milt Jackson and John Clayton at the time. John also talked with Ray. So, when Ray did his 70th Birthday Party in Paris with Roy Hargrove, Art Farmer, Jacky Terrason and Pierre Boussaguet, Ray said, ‘Come on, Queen, only time we got a chance, let’s do this…’ We established a fine relationship. Ray was playing a lot in Zürich back then.”

FM: Speaking of Milt Jackson. You always hear that he didn’t enjoy playing in the Modern Jazz Quartet and that he wanted to get out there and swinging. Do you think that’s true?

AQ: “The Modern Jazz Quartet was a conservative group and John Lewis was a very classical type of person. The group was created company-wise, there was equal share for each musician and it was one of the most exclusive, highly-paid bands. The thing is, they did the Carnegie Hall, tuxedo and bow tie kind of thing but went to places áfter the gig to jam. Connie Kay went to Jimmy Ryan’s a lot. He played with guys like Major Holley and Roy Eldridge. Milt said to me, ‘I can make John Lewis swing, man!’ But if you heard Milt with the MJQ, he sounds different than with Ray Brown and Monty Alexander at Shelly’s Manne-Hole. (That’s The Way It Is and Just The Way It Had To Be – Impulse 1969/70, FM) I played with Milt and Sadik Hakim in Montréal at the time of his Olinga album. I knew where he came from and he was swinging. Anyway, we all did that, jamming after the gig, Coltrane, Stan Getz, everybody.”

FM: You also went to Africa in the early 1970’s. how did that come about and what you did do out there?

AQ: “That was something that came about through the National Endowment of the Arts. Randy Weston and Nina Simone signed up for me in support. I did performances and workshops in ten countries, from Ghana, Gabon, Burkina Faso and Cameroun to Benin, Togo and Zaire. Every African country had embassies in the USA and I played at the residencies of ambassadors in Africa.”

FM: Your album Ashanti is very African in nature. It’s one of your finest records. What was the idea behind that record?

AQ: Well, after we did the music in the studio, I got the idea of doing a drum battle. I played against each track and so, with two drummers going on, we got this special vibe. The name had nothing to do with the Ashanti people. My wife had an old custom mask that she had gotten many years ago in Africa on the marketplace. It’s not an Ashanti mask, by the way. But the first thing I said when we had recorded the album and I saw the mask was, ‘ashanti’. That record was very successful.”

FM: It was released on your record label Nilva. Why did you start your record label?

AQ: I started Nilva because no one was producing me. I made so much money in Europe, I didn’t know what to do with it. I had never made that kind of money. I watched what Charles Tolliver did with Strata-East. I had a radio tape and produced my own record. (Alvin Queen in Europe, FM) Then a friend told me, if you got an ice cream company, you gotta have all flavors… So I went to New York and did the Ashanti record. It took off and I did those records with Dusko Goykovich, Junior Mance. John Hicks was on most of the stuff. I was very close with John Hicks. I produced Ray Drummond’s record with Branford Marsalis.” (Susanita, 1984, FM)

FM: Why did you quit eventually?

AQ: “The business changed. I was a one-man operation. It was impossible for me to put all that stuff on CD.”

FM: As a drummer, you encapsulate both Elvin Jones-inspired playing and straight swing, it’s very interesting to hear.

AQ: “I was there with Tony Williams at the time. I saw the change from time keeping to free playing. I watched Elvin Jones and Roy Haynes, who had started that thing with Sarah Vaughan. He was low in the mix but you could hear it, the triplet style. Tony and Ron Carter played double with Miles. All drummers followed these guys. Later on, in Europe, the older guys would tell me, stop dropping them bombs… We couldn’t play free like that. It was tempo first. All drummers followed Tony and Elvin but no one turned back to Denzil Best or Shadow Wilson or J.C. Heard. But you need them tóo. There’s no background to a lot of players today, you see. If you say, let’s play the blues, they collapse. I’d be glad to teach them! If you pay respect, I’ll help you out.”

FM: You can’t do without the lessons from the elders.

AQ: “I sat around listening to all those stories from Ray Brown and Oscar Peterson. That already is one thing how you learn to play, that’s by keeping your ears open. These guys teach you how to be solid, not to move around. It’s good to play with all these different personalities. Nowadays, it’s technique. The time is weaker than the technique. That’s the problem.”

FM: Perhaps there should be more of those, but I do know young players here in Holland who soak up everything local and international old masters do and have to say 24/7. That’s the spirit.

AQ: “That’s good but the school and industrial system remains problematic. Bandleaders are not supported. The real masters are not supported. I’ve never been supported and I know a lot, you see? What I have to give don’t make money. What they’re giving us is a market of people that aren’t masters yet. In the history of jazz, all new leaders came out of working groups. They came from the bands of Coleman Hawkins, Max Roach, Art Blakey and not from school. I had no problem getting along with the older musicians because I had that type of training at home. Respect your elders. I was in the bands of Harry “Sweets” Edison, Arnett Cobb, Jay McShann, Buddy Tate. If you were with the elders, you stayed out of the conversation. You didn’t have that experience, so it was best to be quiet and learn.”

“Most professional teachers are not real bandstand players. They teach you the notes but not the experience of the bandstand. I tell younger musicians, who you wanna copy? Who you wanna be? I wanted to be Art Blakey, Elvin Jones. I found a sound for myself. I was in the bands of Horace Silver, George Braith, Larry Young. They said, ‘don’t do this, do that, pay attention, take the grime out of your ears, put your mind to it, use the brain, not the notes.’ That’s how I learned. We don’t have that connection between bands and new leaders and that’s a serious problem. Education is great but it’s totally different than the bandstand. I played with everybody on earth. I gave mine but I just watch where things could improve.”

(AQ, Oscar Peterson & Dave Young, North Sea Jazz Festival, 2005; photography Evert-Jan Hielema)

FM: In your definition, the last generation of masters probably is the one that came up in the 1990’s. You played with a lot of those, the Marsalis brothers, Nicholas Payton. Roy Hargrove.

AQ: “Roy Hargrove only played his gigs when he came in and sat in with granddaddies that were lightyears older than him. I was playing a gig with Dado Moroni and Walter Booker and young Roy was sitting on the side of the steps. He hit me in the leg, ‘hey, Mr. Queen, can I sit in?’. ‘Yeah man,’ I said, ‘that’s where the microphone is right there.’ I loved Roy Hargrove. He admired the elders and loved to play with them. He wanted to know where it was at before it was too late. His experience is sadly missed in New York. He had an every-night jam session going on, man.”

FM: So, we don’t have to expect to have any new young masters?

AQ: “Not if we don’t have bands and leaders, we won’t. A master is a guy who can hold a beautiful tone which blends in with everything. In the Basie band, all trumpeters went into a room and each held one note, so it would sound like one. The ‘one note school.’ I used to sit real close and watch the group of Thelonious Monk. I would hear the gut string of the bass. Wilbur Ware would play one note, no amplification, and it went like, BOOM. The bottles rattled behind the bar. They’re masters. One of the problems today is that 90 % of the musicians move around and don’t stay sturdy.”

FM: Are you going to release some new stuff in the near future?

AQ: “I’m working on a new record right now. It has Tommy Morimoto on saxophone. He’s been running around for twenty years but nobody ever gave him a break. Carlton Holmes is on piano and Danton Boller on bass. He was with Roy Hargrove. I met him through Benny Wallace. I don’t want any people with names. I don’t want four bandleaders on stage, there’s gonna be conflict. I’d rather be the only one there.”

“It will feature four-or-five minute tunes like The Night Has A Thousand Eyes and It Ain’t Necessarily So. I want people to listen to the radio and think, wow, where has that song been? The trick in music is to keep it simple. Let it happen, don’t try to make it happen. If your grow, the music is a part of you. With life, you grow. Music is like food. If you’re a chef in the kitchen, the food tastes better years from now than it does at the present because you learn how to cook the food right.”

“I paid my dues, I have a right to make a statement. I never said I was a mentor because I never reach my goal. When I die, I still haven’t reached it. I just go to another dimension. If I reach my goal, there’s no reason to create anymore. Too many people think that they are already there. That’s when you’re blocking your goal. I went to Oscar Peterson and asked him one time, ‘tell me something, how does it feel to be a genius?’ He said, ‘come into the room and shut the door and sit down!’ He said: ‘Look, people say I’m a genius. But I’m an ordinary piano player like you are an ordinary drummer.’ Great wisdom. And when I die, I die with the basics, with the wisdom.”

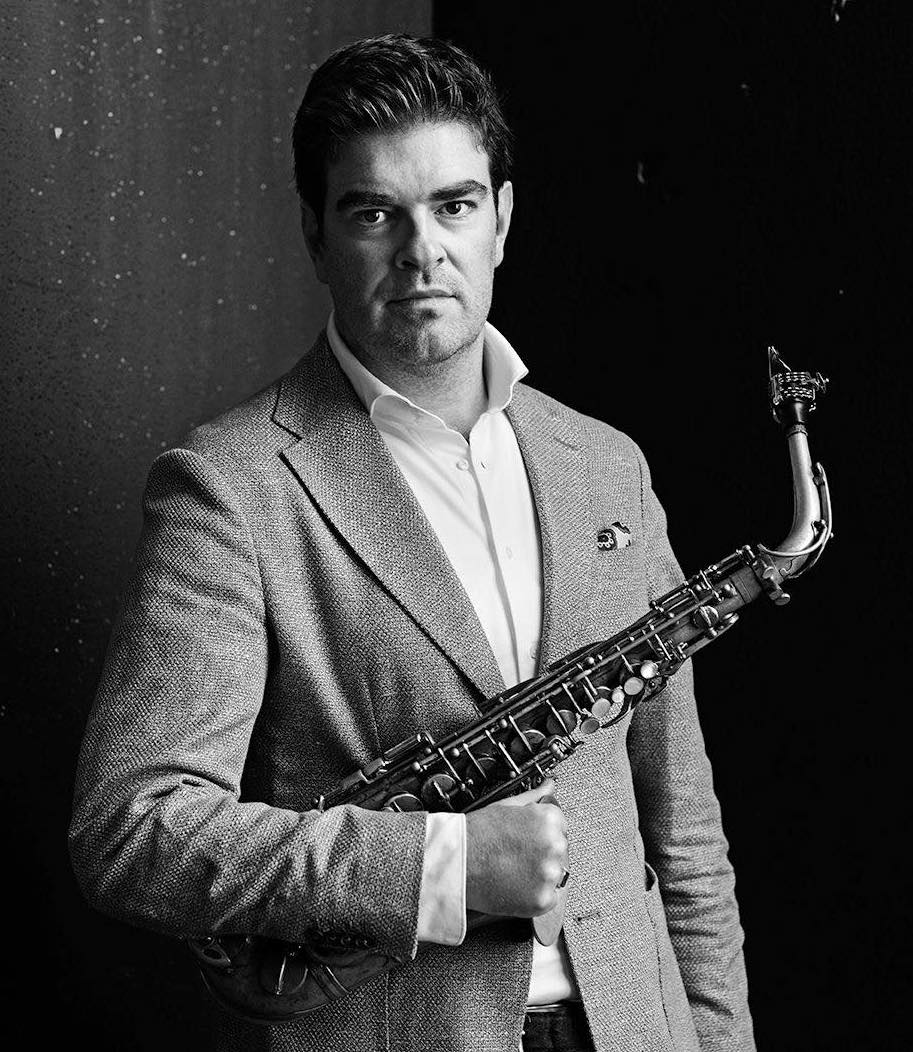

Alvin Queen

Quotes:

Harry “Sweets” Edison: “Alvin reminds me of the original drummers that I worked with in the 30’s and 40’s. He has it all. I have to play at 150% of my capacity. If not, he’ll put me out of stage. Alvin keeps me young every note I play with him. He’s fantastic.”

Clark Terry: “Alvin is one of the most swinging drummers of all time that I know and have played with.”

Ray Brown: “Alvin is not only one of the top drummers for sure but also one of the most swinging and crazy guys that I know.”

Frank Wess: There’s only one Alvin Queen in the jazz world. Period!”

Kenny Drew: “If Alvin leaves the trio, I’ll never hire another drummer.”

Selected Discography:

As a leader:

In Europe (Nilva 1980)

Ashanti (Nilva 1981)

Lenox & Seventh (with Lonnie Smith – Black & Blue 1985)

I’m Back (Nilva 1992)

Nishville (Moju 1998)

Hear Me Drummin’ To Ya! (Jazzette 2000)

This Is Uncle Al (with Jesper Thilo – Music Mecca 2001)

I Ain’t Looking At You (Justin Time 2005)

O.P. (Stunt 2018)

Night Train To Copenhagen (Stunt 2021)

As a sideman:

Charles Tolliver, Impact (Strata-East 1975)

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Jaw’s Blues (Enja 1981)

John Patton, Soul Connection (Nilva 1983)

Guy Lafitte/Wild Bill Davis, Three Men On A Beat (Black & Blue 1983)

Pharaoh Sanders, A Prayer Before Dawn (Evidence 1987)

Tete Montoliu, Barcelona Meeting (Fresh Sound 1988)

Kenny Drew Trio, Standard Request: Live At Keystone Corner (Alfa 1991)

George Coleman, At Yoshi’s (Evidence 1992)

Pierre Boussaguet, Trio Charme (EmArcy 1998)

Cedric Caillaud Trio, Swinging The Count (Fresh Sound 2012)

Check out Alvin’s website here.