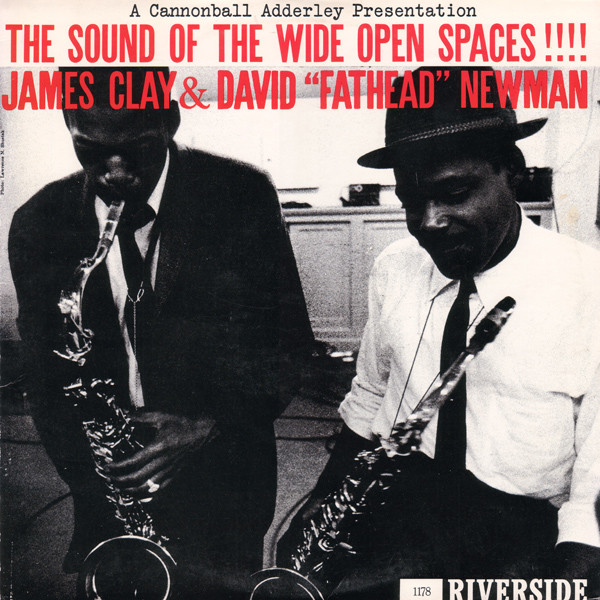

Some sessions just seem to swing harder than others. The Sound Of The Wide Open Spaces!!!! by co-leaders James Clay and David “Fathead” Newman is such an album. A blast from start to finish.

Personnel

James Clay (tenor saxophone, flute B2), David “Fathead” Newman (tenor saxophone, alto saxophone B2), Wynton Kelly (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Art Taylor (blues)

Recorded

on April 20, 1960 in NYC

Released

as RLP 327 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Wide Open Spaces

They Can’t Take That Away From Me

Side B:

Some Kinda Mean

What’s New

Figger-Ration

Think of the combi’s Johnny Griffin/Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Dexter Gordon/Wardell Gray, Arnett Cobb/Buddy Tate or of the Clifford Jordan/John Gilmore album Blowing In From Chicago. The Sound Of The Wide Open Spaces!!!! (the use of multiple exclamation marks is hyperbolic fancy, but I like the way it looks on the jacket) fits into that high calibre category. Clay and Fathead, two ‘tough’ Texan tenors (and alto’s, flutes) battle it out with the hard-driving support of Art Taylor, Sam Jones and Wynton Kelly. The album was supervised by Cannonball Adderley. Adderley, who had signed with Riverside in 1960 and recorded the highly succesful and influential live album In San Francisco, struck up a good rapport with label owner Orrin Keepnews, immediately getting into fruitful A&R territory.

James Clay is still a relatively unknown saxophonist and flute player. Born in Dallas, Texas in 1935, Clay played with fellow Texan tenorist Booker Ervin, but moved to the West Coast in the mid-fifties. By 1960, Clay had recorded with drummer Lawrence Marable (Tenorman, Jazz West 1956), bassist Red Mitchell (Presenting Red Mitchell, Contemporary 1957) and Wes Montgomery (Movin’ Along, Riverside 1960). As a leader, Clay followed up The Sound with A Double Dose Of Soul, which boasts a great line-up of Adderley alumni Nat Adderley, Victor Feldman, Louis Hayes and, again, Sam Jones. A concise but impressive discography. After contributing to Hank Crawford’s True Blue in 1964, Clay disappeared from the scene, only to enjoy a modest comeback in the late eighties.

Clay’s sound is edgy, his style is reminiscent of bop pioneers like Teddy Edwards. A great match with the better-known David “Fathead” Newman. Newman, the big-toned tenorist from Corsicana, Texas, put his highly attractive, blues-drenched style to good use in the Ray Charles band from 1954-64 and ’70-’71, starring on landmark tunes as The Right Time, Unchain My Heart and albums like Ray Charles In Person and At Newport. Newman was an Atlantic recording artist in his own right. On my deathbed, I’m damn sure I will be remembering Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead Newman (Atlantic 1958) as one of the most soulful albums in modern jazz.

Newman takes the first solo on the furiously swinging opener Wide Open Spaces, taking care of business from note one. He sings, spits, guffaws, presenting a lengthy, driving discourse of blues and bop. Meanwhile, Newman’s phrasing is articulate, fluent, and the full-bodied round tone is intact, and his flow is spurred on by clever, unisono figures of Kelly and Taylor. Clay’s tone is more edgy, thinner. Clay finds solace in darkblue, faraway corners, letting loose occasional gutsy, halve-valve sounds and spices a lively tale with labyrinthian clusters of bop phrases, in a sardonic mood, putting you on, enjoying himself. Then he emerges from the shadows with sudden, belligerent wails. Clay’s a more unpredictable player than Newman. Both take zillion choruses to have their say. Never a dull moment.

Wide Open Spaces is a tune written by the legendary bebop singer and poet, Babs Gonzalez. Figger-Ration, an uptempo, tacky bebop showstopper, is also by Gonzalez. The interpretation of Gershwin’s They Can’t Take That Away From Me is hard-swinging. Keter Betts’ blues-based tune Some Kinda Mean starts with the coda, a raucous figure of snare drums and piano, and develops into a mid-tempo, Ray Charles-type mover. Supported by the responsive, burning rhythm trio of Taylor, Jones and Kelly, the latter occasionally chiming in with ebullient bits on the slower tunes and frivolous strings of high notes on the uptempo tunes, Clay and Newman speak confidently on tenor throughout. For What’s New, Newman switches to alto, Clay to flute. It’s a solid rendition of the well-known ballad.

While a current of pivotal game-changing outings (Davis’ Kind Of Blue, Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Coleman’s Free Jazz) was released in ’59 and ‘60, gospel and blues-based hard bop/mainstream jazz, while not always liked by the critics, was at a peak and admired by audiences around the country and abroad. Hard bop albums rolled off the Blue Note, Prestige and Riverside assembly lines like fortune cookies. That turn of the decade was really something! Something of such all-round excellence which might easily cause such marvelous albums like The Sound Of The Wide Open Spaces!!!! to be lightly snowed under. But it aged well. To this day, Clay and Newman’s bopswinging sax festivities leave one breathless with every new turn on the table.