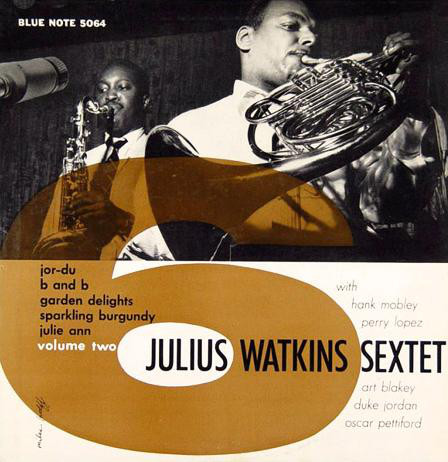

Nobody swung on the French horn like Julius Watkins.

Personnel

Julius Watkins (French horn), Frank Foster (tenor saxophone 1-4), Hank Mobley (tenor saxophone (5, 7-9), George Butcher (piano 1, 2 & 4), Duke Jordan (5-9), Perry Lopez (guitar 1-4, 6, 8 & 9), Oscar Pettiford (bass), Kenny Clarke (drums 1-4), Art Blakey (5-9)

Recorded

on August 8, 1954 and March 20, 1955 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 5053 in 1954 and BLP 5064 in 1955

Track listing

Linda Delia

Perpetuation

I Have Known

Leete

Garden Delights

Julie Ann

Sparkling Burgundy

B And B

Jordu

Jazz soloists on the ‘awkward’ French horn are scarcer than the four-leaf clover. The two biggies and pioneers of modern jazz are Julius Watkins and David Amram. Amram came on the scene at the legendary Five Spot Café in The Bowery in New York City in the mid-fifties and at 90-years old looks back on a career as indigenous player and composer in jazz and popular music. Julius Watkins, born in 1921, unfortunately only went as far as 1977. Regardless, the Detroit-born French horn player must’ve looked back with pride. His legacy is impressive.

Need a French horn? Call Julius. He’s omnipresent as soloist and part of big ensembles. To give you an idea, Watkins was associated with Milt Jackson, Oscar Pettiford, Thelonious Monk (Monk, Thelonious Monk & Sonny Rollins), Donald Byrd, Quincy Jones, Miles Davis (Porgy & Bess), Gil Evans, Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, Randy Weston, John Coltrane (Africa/Brass), Johnny Griffin, Tadd Dameron, Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra and McCoy Tyner. Watkins co-led The Jazz Modes with tenor saxophonist Charles Rouse from 1956 till ’59.

Isn’t it wonderful how jazz musicians managed to incorporate such oblique European instruments as French horn? I love the sound of the instrument, bittersweet, silk and satin, like thin air, like the voices of angels that have slept off their wining and dining. The horn is lovely supportive to big ensembles, providing a soft landing for the crackling brass of trumpet and trombone. It was like wax in the hands of Julius Watkins. His fluidity on the instrument was virtually unparalleled. His sound is rich and flexible, varying from cushion-soft reveries to tart calls to arms. You hear those stories about how classical music pros from the big symphonic orchestras were stunned to hear what kind of unbelievable stuff legends like Louis Armstrong coaxed from their instruments and imagine many will have been fascinated by the efforts of Julius Watkins. See what Julius was able to do with the horn in this YouTube excerpt of his hand-muted solo with Quincy Jones in 1960. Fantastic.

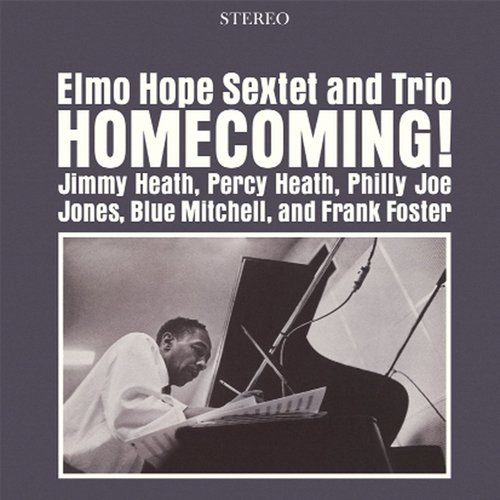

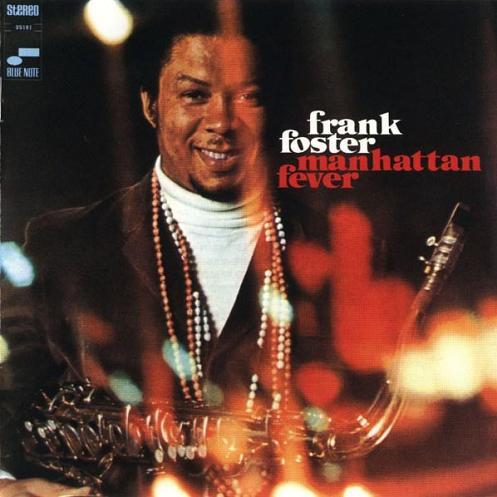

Watkins recorded his leadership debut on Blue Note in 1954 and ’55, two 10 inch records that were belatedly repackaged on CD in 1995. At least to my knowledge Blue Note did not re-release the sessions on the new 12 inch format soon afterwards, as it usually did with their 10inch platters like the New Stars New Sounds LP’s. Am I right? Anyway, the sessions consisted of top-notch hard bop with the cream of the crop, the first session featuring tenor saxophonist Frank Foster and drummer Kenny Clarke, the second session featuring Hank Mobley, pianist Duke Jordan and drummer Art Blakey, all of them underlined by bassist Oscar Pettiford. Pleasant surprises are provided by guitarist Perry Lopez and pianist George Butcher.

The highlight of the first session is Linda Delia, which takes us down to Mexico on a beat that’s as lively and fulfilling as the smile of a baby, engendered by Kenny Clarke’s masterful finger strokes and rolls, and includes a brilliant, clattering entrance by Watkins, who sustains the jubilant feeling with a diversity of sunny colors. Guitarist Perry Lopez, a kind of mix between Kenny Burrell and Jimmy Raney throughout the two sessions, is especially cool. All-rounder Frank Foster is another asset of this top-notch BLP 5053 record.

BLP 5064 beats this to the punch, though, Blakey unusually forceful with the brushes, Mobley’s smooth sound blending particularly well with Watkins’s sweet and sour stories, Duke Jordan laying down some of his most urgent and pleasantly bouncy lines of that era. Here, amongst the sultry Garden Delight and an early version of Jordan’s instant classic Jordu, the sprightly boppish Sparkling Burgundy stands out, a title that couldn’t have been more appropriate. This band pops the cork with some bubbly, captured beautifully by the legendary Rudy van Gelder, at that time still working from the living room of his parents in Hackensack, New Jersey.

Killer sleeve of Vol.2 as well.