Survivor. Last of the Mohicans. Royalty. Alvin Queen signed, sealed and delivered his statements in classic jazz. In part 1 of our interview, the veteran drummer talks about growing up in Mount Vernon, NY, the roots of the black beat, sitting front row at Coltrane’s epic Birdland performance besides ‘mentor’ Elvin Jones at age 13 and finding his way as a young professional with Wild Bill Davis, George Benson and Horace Silver. “We were set up during one of the most beautiful times in music.”

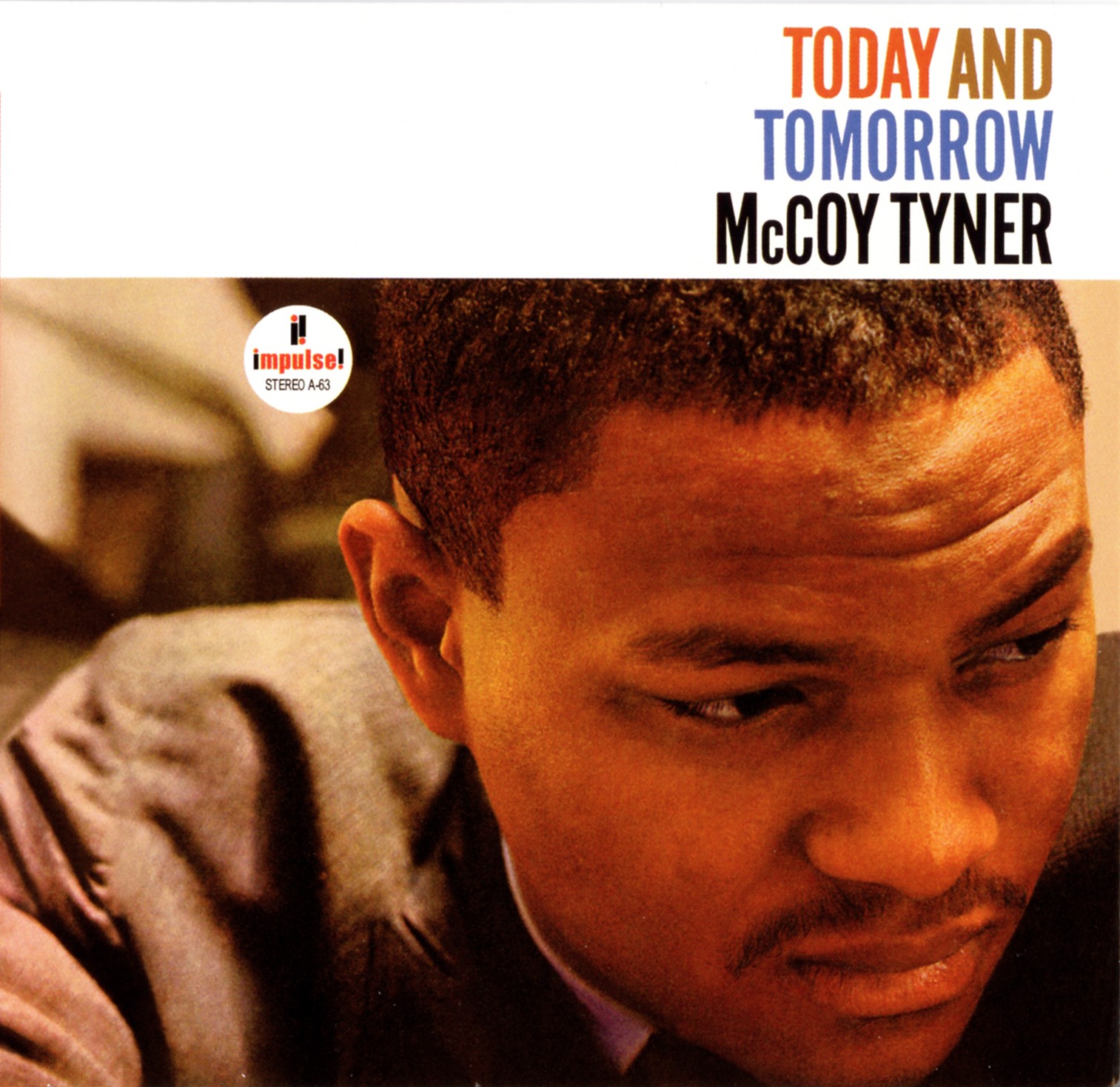

The camera reveals a strong man. Pronounced jaw lines. Plenty muscle. The type that was like a leopard on the court in the hood, dunking methodically and swiftly. The type that carries nephews on his shoulders at the fairground. His body is like his beat. And his beat is very strong. It’s like an unbreakable wheelbarrow. To put extra weight into his words, Alvin Queen regularly bends forward, adding a resolute “okay?!” or “you see?!” He’ll tell you where it’s at, where it’s been and where it should go. A preacher, beyond any doubt. A very generous one, at that. It is impossible to avoid the legendary drummer’s twinkling eyes. They speak of love for his art and trade. They speak of the serious fun of endlessly discussing those. They speak of the giants of jazz of lore.Alvin Queen oozes classic jazz. At age 73, he looks back upon a spectacular career that gained momentum when he was taken under the wings by Elvin Jones and developed into the to-go-to rhythm pal of Wild Bill Davis, George Benson, Horace Silver, Ray Brown, Harry Sweets Edison, Eddie Lockjaw Davis, Kenny Drew and Oscar Peterson, among many others. Queen migrated to Geneva in Switzerland in the 1970’s and started the record label Nilva. A figurehead of the European scene and a middle-aged class act with truckloads of experience, he adopted the new breed and played with the Marsalis Bros, Roy Hargrove, Nicholas Payton, Mike LeDonne, Eric Alexander, Christian McBride and Jesse Davis.

Those were the days when hand-written letters were something to cherish. Now we have the avatar of Elvis Presley putting another gig in his hip pocket in Las Vegas. People adjusting their blinds with their smart phones while they’re drinking cocktails at a sidewalk café in Malaga, Spain. A world of difference. But no mistaking, Queen has both feet on the ground of the 21st century. Although he is critical of the system that breeds well-intentioned but ignorant young players, he still likes to play with talented young lions, preferably those that deserve wider attention. His latest tribute to Oscar Peterson, Night Train To Copenhagen, features a couple of fine young Danish fellows that fly by the digital highway from the word go. Queen: “My Oscar Peterson tributes did very well. The first one from 2018, O.P., went BOOM to the charts, then Night Train To Copenhagen went BOOM up the charts as well, up to number 3 out of 100 best albums in the USA last year. I am not doing anything out of the ordinary. I’m playing normal music. I can’t change music. Most of the best composers in the world, they’re dead and gone. I’m playing the kind of melodies that people can understand.”

(Tobias Dall, AQ and Calle Brinkman, the Night Train To Copenhagen trio.)FM: You grew up in Mount Vernon, New York. What was it like?

AQ: “Great. We had after-school programs those days. Every kid had something to join, like a band or a swimming team. I followed the roots of my brother, who played drums. Kids had drumsticks and banged on the sidewalk. I lived in a black neighborhood and there was a lot of exposure to music. You had these little cafés that sold hot sausages and had a jukebox. We would bang on the side of the jukebox. Everybody had some kind of rhythm going on. There was music all up and down the streets. All cafés opened the doors because there was no such thing as air-conditioning. I would sit on the stoop, eat ice cream and listen to the music. Billy Eckstine, Arthur Prysock. My brother didn’t keep the drums going and I joined the school band. We would do parades. This was about 1958/59. My mother went Christmas shopping down the avenue. There was this store window, Woolworth’s dime store I think it was, and up there was a little kid and a guy who was teaching him drums. I kept looking, thinking, how in the hell can I get up to this guy… one day when my mom is not around… So, one day I did. I was a shoeshine kid with a little box. I went to the illegal skin joints, got a quarter or fifty cents. I went up Fourth Avenue, the guy was Andy Lalino, he had worked with Neil Sedaka. I said, ‘you want a shoe shine?’ Just a nosey kid, you know. ‘No, no, no,’ he said. ‘You play drums?’ ‘Yeah’, I said, ‘I’m in the school marching band’. He said: ‘Tell your mother to call me.’ She did and I got lessons for two months. But it was 5 dollars an hour. And my mom was on social service. She was on welfare. I had two brothers and sisters. Money didn’t stretch that far. Lalino said, ‘Miss Queen, he’s a nice kid, I don’t wanna see him go bad in the street. He can stay here, run coffee errands, sweep the floors, I give him his lessons.’”

“I grew up with Denzel Washington, the actor. His father was a minister at the church where I went. My grandmother played piano and directed the choir. My father was working the bars as a bar manager. There were about six jazz clubs in one square mile. We weren’t allowed in white areas so much, we had everything in our own neighborhood. One day, in one of those clubs, Jimmy Hill had a gig but something happened to the drummer. Jimmy went to the bar where my father was manager. My father’s nickname was Dead Eye and Jimmy said, ‘Dead Eye, the drummer didn’t show, could we use the kid?’ I was eleven years old! My father said, ‘can you do this, Alvin?’ I said, ‘Dad, if there’s any music that they play that is in your record collection, I can help!’ ‘Ok’, he said, ‘put your suit and necktie on.’ My dad was chaperone. That was the first gig that I played. I knew all the music. At drum school we played along with records of Dinah Washington. Dance music.”

FM: What music did you play that night? Swing?

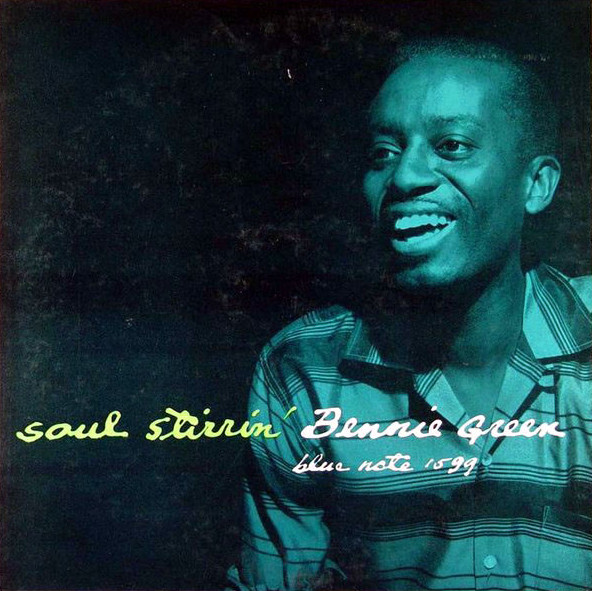

AQ: No, no. Art Blakey. Chicken ‘n’ Dumplins. The Blue Note stuff. Shuffles were very popular. Jimmy Smith’s The Sermon. We knew all those records by heart because we heard ‘m all the time. All those tunes that guys like Symphony Sid put on air.

FM: How much influence did church and gospel have on you?

AQ: “In the first place, the thing about the black churches was, if you didn’t go to church on Sunday, you couldn’t go out and play on Saturday. Inside the church we had big mamas. Everybody watched each other’s kids. If you played hookie, somebody told your mother or father and they would say, where were you!”

“I would see grandmothers play tambourines and how they beat the rhythms. You would see upright basses and a piano player that played on a piano that had broken keys and was out of tune. There was the organ, that was a black thing. All great organ players came out of church. When you see exactly what was happening from gospel, blues, the shuffle rhythm to rock and roll and Little Richard, Tina Turner, The Beatles, you see one pattern. This is the gospel root. The whole thing about it, it’s 6/8 or 12/8, counted in triplets. That is what makes it swing. In school they teach them to play in sixteenth notes but that’s not swinging. I always try to explain to students and everybody, count in triplets and play the ¾. Listen to Gene Harris & The Three Sounds and Lil’ Darlin’ for instance, you’ll hear it. All triplets going on. See where all the accents are falling. It’s how you interpret it. I play all rhythms in one beat. A lot of people want to play with me because they think, that guy has got an ‘older’ right hand. I care about the definition of the beat. That’s what the musicians need. I believe in a solid, sturdy beat.”

FM: Your father regularly took you up to Harlem and the Apollo Theatre. That’s very generous.

AQ: “At that time, black people had process hair. They mixed lye and potato and straightened their hair. Look at Oscar Peterson, Nat King Cole, Erroll Garner. They had to do this once a week or every two weeks. The famous boxer, Sugar Ray Robinson, opened a barbershop in Harlem. My father frequented his shop and always said, ‘Alvin, after I have my hair done, we’ll get you a hot dog and see the show’. I saw Stevie Wonder, The Jackson Five, The Supremes, Count Basie, John Coltrane, entertainers as Pigmeat Markum and actors like Red Foxx. They had a Gospel Caravan. Afterwards, we would buy the records across the street at Teddy McRae’s record store. Music was like food.”

FM: You mentioned that you were a shoeshine boy. I read that you shined the shoes of Thelonious Monk. Pretty crazy! How did something like that come about?

AQ: “Yeah, they had Beefsteak Charlie’s at 50th Street and Broadway. I was a kid and listening where these guys hung out. I’d use the shoeshine box again, just like I did in Mount Vernon. Coleman Hawkins hung out there when he was doing studio work in New York. I’d say, ‘you want a shine?’ to Hawkins, Monk, Buck Clayton, Cozy Cole… All those guys worked at the Metropole, which was close by. They would say, ‘hey, young boy, gimme a shine!’. They never pushed you away, they always behaved like decent adults.”

FM: You also went to something like the Gretsch Drum Night, right?

AQ: What happened was, the guy that taught me drums in Mount Vernon, he got permission from my mother to take me to a drum show downtown at the Roseland. Elvin Jones was the guest and we got very close. That was in 1962. Then the teacher chaperoned me to the Gretsch Drum Night. They had Red Garland on piano and I think Paul Chambers on bass. Elvin Jones, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Mel Lewis and Charli Persip took turns. For some reason, Elvin said, ‘get him up there’… I played and it was the biggest thing they’ve seen, man this kid is playing! Birdland was just across the street. I hung out there and saw Eric Dolphy, Wes Montgomery.”

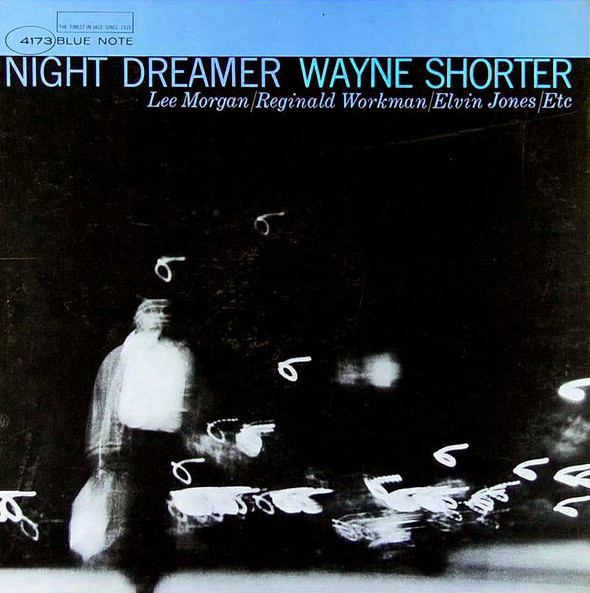

FM: At Birdland, you saw John Coltrane perform what would be recorded as part of the famous Live At Birdland album in 1963. At the tender age of 13! Please tell me how that came about.

AQ: Yeah, it was my teacher that took me out again. That was the night that Coltrane met his future wife, Alice. There were always two bands playing at Birdland and she was playing with Terry Gibbs. Of course, she was still Alice McLeod then. Anyway, I was sitting at the table with Elvin. He said, with that deep, gritty voice of his, ‘the kid’s got to learn, the kid’s got to learn’. He picked me up and put me up there with Coltrane. I’m making all these sounds. I remember John Coltrane turning around and saying, ‘Elvin, get the kid, man!’ Haha!”

FM: Do you remember what tune you played?

AQ: I don’t remember the tune! I was in a state of shock. It lasted for maybe five or ten minutes. I was young, my hands weren’t that strong as Elvin’s. Elvin put me back at the table. One thing Elvin and Art Blakey always did, they took you right under them, you could watch their feet and see what they were doing.”

FM: So, you were mentored by Elvin after that?

AQ: Off and on. I would follow Elvin around, me and guys like Reginald Golson, that’s Benny’s son, who also was a drummer and died. We stayed at The Peanut Gallery at Birdland. We were allowed to sit there because we were kids. We weren’t allowed at the bar. During breaks musicians would come over. All of them talked with the kids.

FM: Your first professional gigs were with singer Ruth Brown and organist Wild Bill Davis.

AQ: Yes, I don’t even know how I got that gig with Wild Bill. We went to Atlantic City and played at Grace’s Little Belmont club. It was a chicken ‘n’ waffles bar. After that I joined the organ circuit. Everything was organ at the time. They needed drummers all the time. So, you go and hang out in a bar in Harlem. That was how I got in touch with Grant Green and people like that. He would say ‘hey young boy, what are you doing next week?’ ‘Oh, Sir,’ I would say, ‘I’m not doing anything.’ ‘Okay, have your drums ready on Monday at 7:30, we’re going out of town…’. That probably was with John Patton. All organ players had a trailer. I started working with Don Pullen. He is best-known through his work as pianist with Mingus and George Adams but he also played the Hammond organ. I played with him and Ruth Brown. Then I played with guitarist Tiny Grimes at Sue’s Rendezvous at 115th Street. You don’t even know who they really are, you’re just making gigs.”

FM: You also played with George Benson around that time.

AQ: Yes, he was with Ronnie Cuber and Lonnie Smith. George sang a lot in the car, but he wasn’t a singer yet. I remember that we went to Buffalo one time. There was a snowstorm and so we were snowed in. We were playing the Beemose club but there weren’t any people. Nobody. ‘Who you’re playing for?’ said the owner. ‘Man,’ I said, ‘I want my money.’ ‘Okay,’ he said, ‘cool it, have a drink…’. Then B.B. King came in with two young ladies. He also had a gig and was snowed in as well. He said to George, ‘George, if you change up your style a little bit, you’ll probably be successful.’ That’s when he came up with Breezin’, the big hit.’

FM: At the same time, you joined Horace Silver. How did that come about?

AQ: I auditioned and got a call from Horace Silver in September 1969. I had to have a suit, went to a pawnshop on 8th Avenue, purchased two cases for the drums and joined the union. I had to have a cabaret license. Me and Tony Williams, we were young and always had trouble with police cards and fingerprints. Union delegates would come and check, we couldn’t play with any name bands a lot of the time. At that time, Horace had Bennie Maupin on saxophone, Randy Brecker on trumpet and John Williams on bass. Silver would take a vacation each year, I was with him for nine months and would do the other three months with George Benson. That’s how it worked.”

Next time, part 2, Alvin Queen talks about his reconnecting with Silver in the 1970’s, his migration to Switzerland and pivotal role as drummer with the elderly jazz legends and explains the difference between classic and contemporary jazz…

Alvin Queen

Quotes:

Oscar Peterson: “Alvin is one of the best drummers that I ever shared the stage with. He has a great sound and time feel. He plays with fire and I really love it.”

Elvin Jones: “Alvin has something that I don’t have and will never have: precision. I love him!”

Pierre Boussaguet: “Alvin’s backbeat is unique in this world and when he plays a ballad, you hear each time clear and wide. Amazing.”

Benny Carter: “Alvin knows exactly what to give to every musician in the band to play at their best. I love him.”

Butch Miles: “I wish I could have Alvin’s chops! He’s so fabulous!”

Calle Brickman: “Apart from his amazing musicianship that I listened to on records throughout my life, Alvin is also a great person. He is happy to share his views on music and life, which is the way jazz tradition has been brought through the generations. A true friend and a historic figure in jazz.”

Selected Discography:

As a leader:

In Europe (Nilva 1980)

Ashanti (Nilva 1981)

Lenox & Seventh (with Lonnie Smith – Black & Blue 1985)

I’m Back (Nilva 1992)

Nishville (Moju 1998)

Hear Me Drummin’ To Ya! (Jazzette 2000)

This Is Uncle Al (with Jesper Thilo – Music Mecca 2001)

I Ain’t Looking At You (Justin Time 2005)

O.P. (Stunt 2018)

Night Train To Copenhagen (Stunt 2021)

As a sideman:

Charles Tolliver, Impact (Strata-East 1975)

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Jaw’s Blues (Enja 1981)

John Patton, Soul Connection (Nilva 1983)

Guy Lafitte/Wild Bill Davis, Three Men On A Beat (Black & Blue 1983)

Pharaoh Sanders, A Prayer Before Dawn (Evidence 1987)

Tete Montoliu, Barcelona Meeting (Fresh Sound 1988)

Kenny Drew Trio, Standard Request: Live At Keystone Corner (Alfa 1991)

George Coleman, At Yoshi’s (Evidence 1992)

Pierre Boussaguet, Trio Charme (EmArcy 1998)

Cedric Caillaud Trio, Swinging The Count (Fresh Sound 2012)

Check out Alvin’s website here.