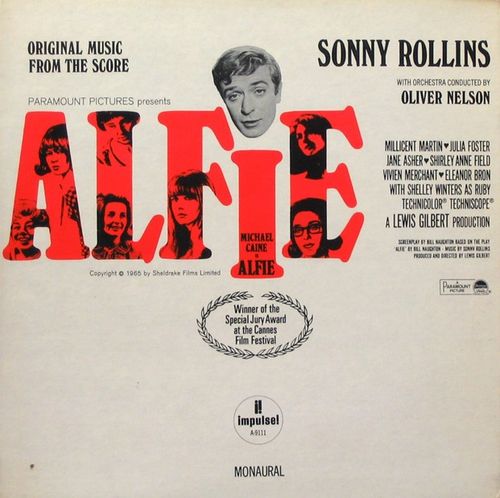

Alfie, the Sonny Rollins soundtrack of the prize-winning English movie starring Michael Caine, deserves to be ranked alongside Saxophone Colossus and A Night At The Village Vanguard as one of the tenor saxophonist’s major achievements. Largely on account of his unbelievable improvisations in Alfie’s Theme.

Personnel

Sonny Rollins (tenor saxophone), Bob Ashton (tenor saxophone), Phil Woods (alto saxophone), Danny Bank (baritone saxophone), J.J. Johnson (trombone A1, A2), Jimmy Cleveland (trombone A3 B1-3), Roger Kellaway (piano), Kenny Burrell (guitar), Walter Booker (bass), Frankie Dunlop (drums), Oliver Nelson (arranger, conductor)

Recorded

on January 26, 1966 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as A-9111 in 1966

Track listing

Side A:

Alfie’s Theme

He’s Younger Than You Are

Street Runner With Child

Side B:

Transition Theme For Minor Blues Or Little Malcolm Loves His Dad

On Impulse

Alfie’s Theme Differently

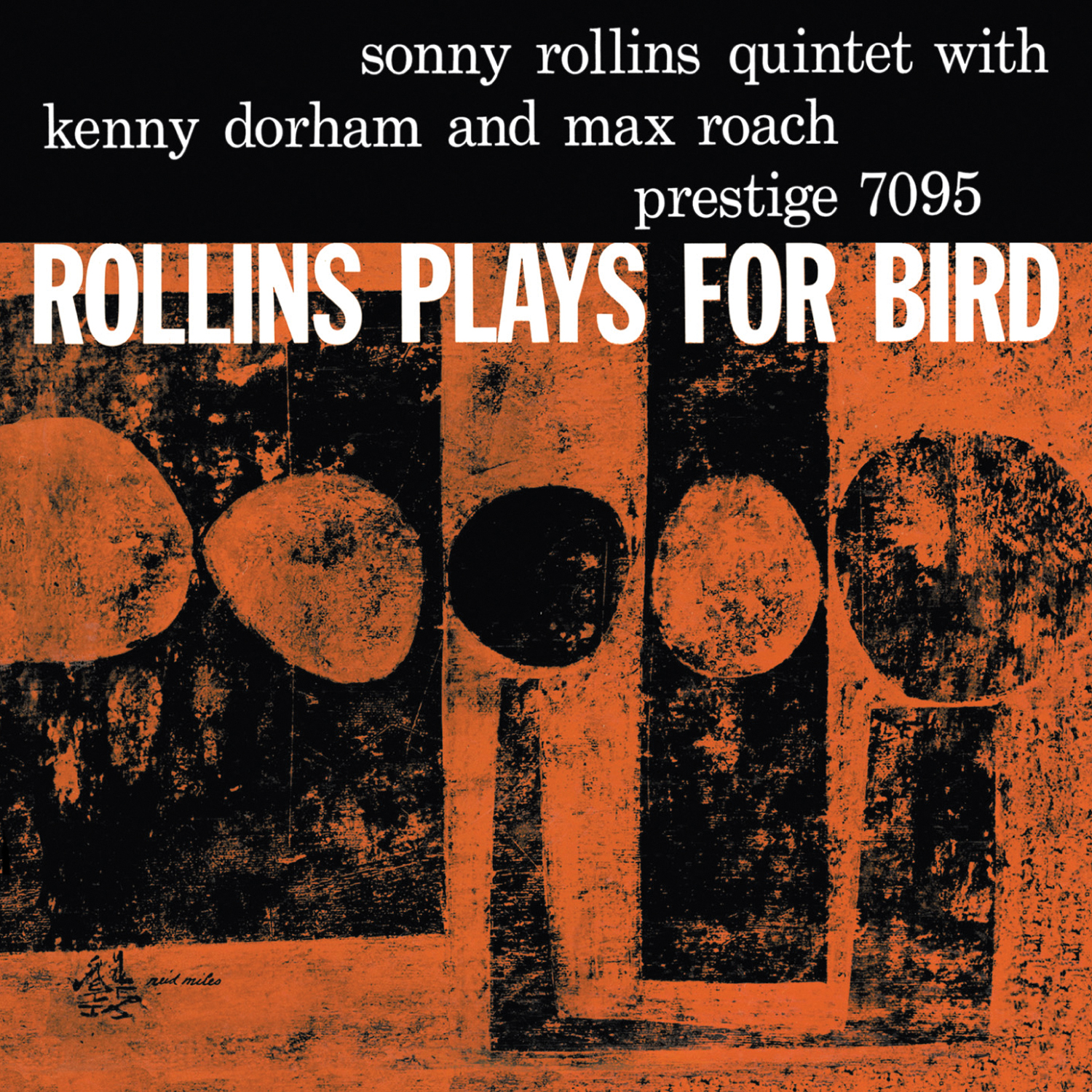

In the years preceding

Alfie, Sonny Rollins had developed into a top-rank performer able to bid a high price for his beloved art form. A lucrative contract with RCA after the tenorist’s legendary, mysterious sabbatical ‘under the Williamsburg Bridge’ from 1959 to 1961 led to a series of five albums for the major label, starting with

The Bridge, ending with

The Standard Sonny Rollins. In the early and mid-sixties, Rollins, always the contemplative intellectual, self-critical to the point of exhaustion and switching between sidemen continuously, was on a constant search for new means of expression. Keeping it fresh, tryin’ or dyin’, elusive as far as style is concerned, Rollins defied a sound definition of his personality. Albums with standards and the sole bossa tune alternated with extremist free jazz outings like

Our Man In Jazz in 1962 and the intriguing, endearing cooperation with Coleman Hawkins on

Sonny Meets Hawk in 1963. 1965’s adventurous

On Impulse preceded

Alfie, which was followed up by the full-blast avantgarde effort with John Coltrane’s famous associates Elvin Jones and Jimmy Garrison plus Freddie Hubbard,

East Broadway Run Down, a high-level album that, however, didn’t fully delivered on its promise. On the other hand,

Alfie becomes more beautiful with every turn on the table.

Given the sensitivity and critical attitude of Rollins in regard to obtrusive sidemen, particularly pianists, it is remarkable that the large ensemble context of Alfie works so well. Oliver Nelson’s flexible, spot-on arrangements keep Rollins on his toes. If there is one let-down on this album, it is the fact that the couple of major league colleagues in the reed chairs, Phil Woods and J.J. Johnson, aren’t allowed solo space. Kenny Burrell and Roger Kellaway have ample room to make their mark, and, admittedly, make the most of it. Kellaway’s gentle touch contrasts nicely with the forceful Rollins and the pianist performs particularly well in Alfie’s Theme Differently, building on the dying notes of Rollins’ off-centre bits with zest. Burrell is peppery throughout, switching between fluently archetypical blues lines, shimmering clusters of notes and crunchy chords.

The bit of undercooled, breathy balladry of Rollins in He’s Younger Than You Are is a genuine nod to Coleman Hawkins. But before you know it, Rollins has ended the tune with a sweeping arc of majestic wails. Rollins, the rhythm king, is in evidence on Street Runner With Child, a collage of romantic solo piano, fast-paced blaxploitation flic-type flights and the recurring reference to Alfie’s Theme, is the only tune on the album that reminds us of the fact that Alfie is a soundtrack. The free playing of Rollins, mixed interestingly with a constant eye on the melody, is most evident in Alfie’s Theme Differently and Transition, while the contrast between the lithe rhythm and meandering lines of On Impulse (a title made up on impulse while Sonny was thinking about his album On Impulse also on the Impulse label the year before?) ignites a dreamy vibe.

Rollins in a great mood. It’s getting even better, because, without the shadow of a doubt, Alfie’s Theme is the albums’s hors d’oeuvre. The large ensemble transports the catchy line to the terrain where Ray Charles drove his tunes home to in the fifties. Drive. Propulsion. Courtesy of Oliver Nelson’s fleshy, well-timed horn sections and the probing rhythm tandem of bassist Walter Booker and drummer Frankie Dunlop. Burrell and Kellaway flourish, but Sonny Rollins is the star of the show, performing one of his all-time great solo’s. In a structured exploration of the basic theme, Rollins grabs the melody by its sleeve. Then he pauses deliberately for a while, like a girl that’s playing hard to get, indulges in a rumble of percussive blocks of short-ringing notes, lingers on new notes like a guest savoring a star restaurant dessert, wanders off into the avantgarde jungle, subsequently swings back into bop mode, alternating double timing, honks and forceful wails, moving into scales with the flick of a, highly skilled, tongue and continues to blow confidently over the sounds of the repeated brass and reed statements. Rollins explores every corner of the melody, rhythm-wise, harmony-wise, returning to it almost every few bars and all the while displaying his big, imposing sound. Rounding off the proceedings in style, Rollins ends his solo with an explosive note.

Lots of proteines in the meal of Sonny, which after all, maybe, wasn’t a high-brow dinner but a reinvigorating eggs and sausage and a side of toast, coffee and a roll, hashbrowns over easy, chili in a bowl, with burgers and fries (now, what kinda pie?)… Full stomach tenor! Sonny Rollins at his best, speaking eloquently to both mind and soul. And as a natural consequence, a peak moment in jazz.