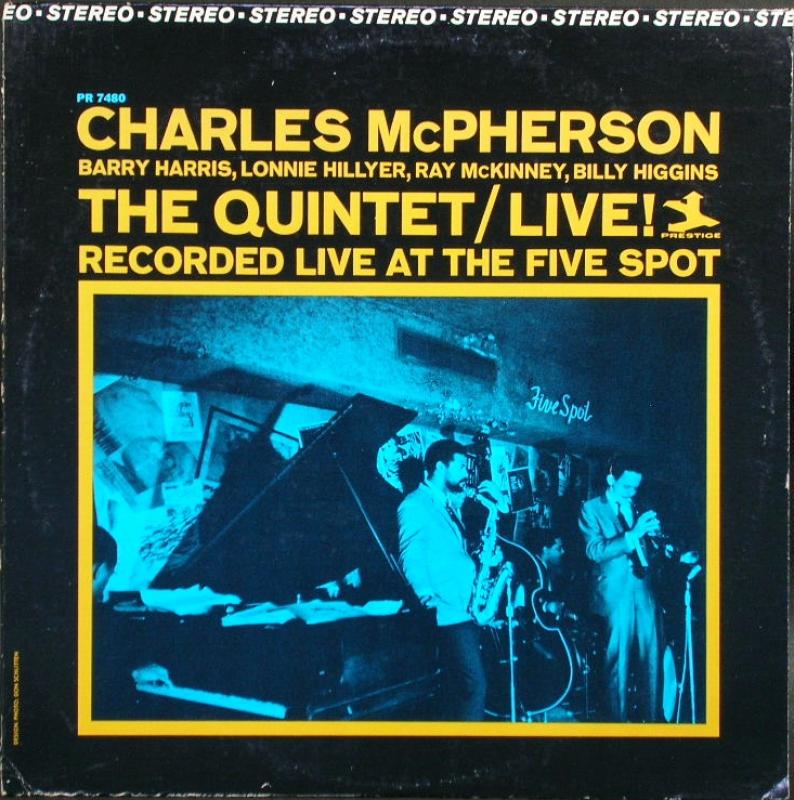

Altoist Gene Quill once walked off the stage, when a malignant member of the audience quipped: “All you do is play like Parker!” Whereupon Quill pushed his horn forward and replied: “You try to play like Charlie Parker!”* Discussions on Charles McPherson usually ran along the same lines. In the sixties, McPherson was often set aside by critics as a mere imitator of Bird. Too bad. Quills’ perky remark suggested it was far from easy to play Parker’s complex and spirited music. Yet, cats like McPherson carried on the flag of the Parker legacy eloquently and with great pride. For that, it would’ve been more than reasonable to be thankful.

Personnel

Charles McPherson (alto saxophone), Lonnie Hillyer (trumpet), Barry Harris (piano), Ray McKinney (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded

on October 13, 1966 at the Five Spot, NYC

Released

as PR 7480 in 1967

Track listing

Side A:

The Viper

I Can’t Get Started

Shaw ‘Nuff

Side B:

Here’s That Rainy Day

Never Let Me Go

Suddenly

Undeniably, the influence from Bird on McPherson is evident throughout his career. Certainly on his live album The Quintet/Live!. But for all McPherson’s (articulate and furious) bebop sparks, as heard on the album’s highlight, Bird’s Shaw ‘Nuff, McPherson had grown into an alto saxophonist with a singular, vibrant style. A style appreciated by giant of jazz Charles Mingus, in whose group McPherson intermittingly played from 1960 to 1974, notably on Live At Town Hall and Music Written For Monterey 1965.

Beside being a first-class player in the bop and hard bop vein, McPherson proofs to be an outstanding balladeer as well. The attraction of Never Let Me Go lies in the combination of the altoist’s darkly lyrical mood, husky delivery and long lines alternating with swift phrasing. He also tells a sweet and sour story on Gershwin’s I Can’t Get Started, on which his interaction with pianist Barry Harris is particularly responsive. Harris nudges fellow Detroit-native McPherson into interesting directions and turns in an exquisite solo. Foremost bop interpreter Harris had mentored McPherson in the late fifties. Harris obviously pulls a lot of strings on this date, displaying sympathetic accompaniment, confident command of harmony and melodic finesse.

Drummer Billy Higgins, tasteful and propulsive, is a strong force as well. Crowd-mover The Viper has a similar vibe as Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder, a hit that thanked its success for a big part to Higgins’ indomitable, fresh beat. (Barry Harris played on The Sidewinder as well) Greasy statements by McPherson and trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer (another Detroit friend and a colleague from the groups of Mingus and Barry Harris) are followed up by a percussive Barry Harris solo, who makes use of Monk-like delayed time.

The ‘Latinised’ Here’s That Rainy Day includes intriguing variations on the melody by McPherson. On the driving hard bop waltz Suddenly Lonnie Hillyer is in a Don Cherry mood. Both are fine performances. Shaw ‘Nuff, however, is of another order. McPerson cum suis set up an appropriate breakneck speed for Charlie Parker’s madly beautiful tune. It’s a lightning bolt. So fast Hillyer has trouble keeping up, both melody and solo-wise. McPherson’s solo is full of fire. Barry Harris seemingly effortlessly displays his vast knowledge of Bud Powell, brilliantly and suavely running through the complex changes. Both soloists thrive on the fierce, articulate backing of Billy Higgins and bassist Ray McKinney.

The Quintet/Live! contains varying repertoire, dynamic group interplay, a warm live atmosphere and immaculate improvisation by both leader and ‘consiglieri’ Barry Harris. An essential McPherson album.

*The little piece of jazz lore involving Gene Quill is chronicled in bassist and jazz writer Bill Crow’s wonderful and insightful book Jazz Anecdotes.