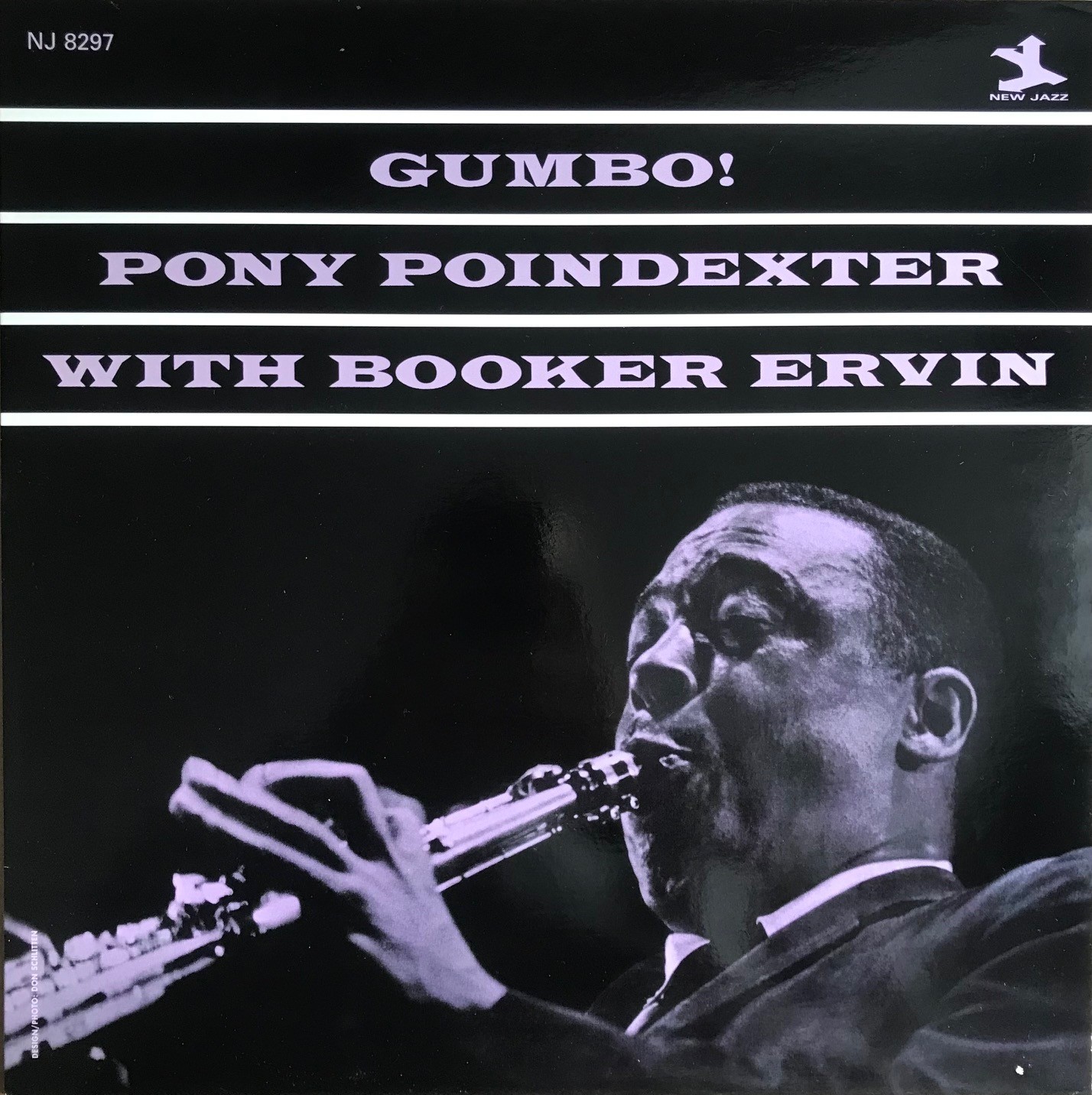

Pony in the parade.

Personnel

Pony Poindexter (alto saxophone, soprano saxophone), Booker Ervin (tenor saxophone), Al Grey (trombone), George Tucker (bass), Jimmy Smith (drums)

Recorded

on June 27, 1963 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as NJ-8297 in 1963

Track listing

Side A:

Front ‘O Town

Happy Strut

Creole Girl

4-1-44

Side B:

Back ‘O Town

Muddy Dust

French Market

Gumbo Filet

Pony Poindexter spent most of his life on the West Coast, in Spain and Germany, but he was born and raised in New Orleans. So, he had every right to dedicate a record to The Big Easy. It’s a goodun. Nothing stunning or sensational but you can feel that it’s from the heart, Poindexter sharing his memories of growing up in the unique melting pot in the Delta, bringing those memories to life with a batch of entertaining, buoyant and blues-drenched tunes. He’s giving us lots of different flavors, little stories about funeral parades, creole girls, gambling and food, not to mention, the indispensable ingredient of voodoo, that mythical catch-all for all kinds of weird forms of superstition, as manifest a link to African roots as they come.

Till age 11, Poindexter lived in New Orleans, when his parents moved to San Francisco. It was there that Poindexter hooked up with the Billy Eckstine band, a playground for many jazz greats like Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, Gene Ammons. Poindexter played in Eckstine’s band from 1947 to 1950, subsequently joining Lionel Hampton, also a quick-witted assembler of marvelous talent. The great singing group of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross was Poindexter’s next notable employer in the early 1960’s. In 1963, Poindexter stayed in Paris. As so many American jazz artists, he liked what he saw. Poindexter permanently moved to Europe. He lived in Spain and Mannheim in Germany for almost twenty years. Finally, Poindexter returned to the USA. He passed away in Oakland in 1988.

Relatively underrecorded, Poindexter started as a leader with Pony’s Express on Epic, which sports a staggering line-up including Eric Dolphy, Dexter Gordon, Ron Carter and Elvin Jones. He then continued with Plays The Big Ones on New Jazz, a shamelessly commercial affair that included a take on Elvis’s Love Me Tender. Then, in Europe: out of sight, out of mind. Poindexter seemed to concentrate on gigging mainly, though Alto Summit with Lee Konitz, Phil Woods and Leo Wright stands out.

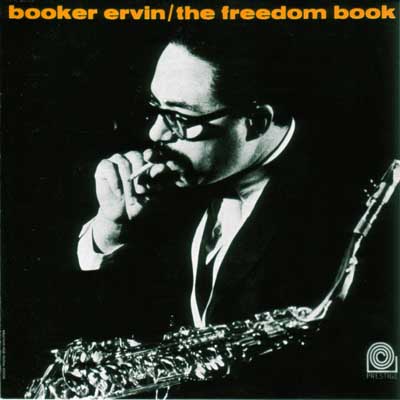

Plays The Big Ones featured pianist Gildo Mahones, bassist George Tucker and drummer Jimmy Smith, who were Poindexters’s colleagues from Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. Poindexter took them into the next session that spawned Gumbo!, which is much more personal and much better. Poindexter further assembled tough but modernist tenorist Booker Ervin and trombonist Al Grey, magnificent growler, perfect foil for that ol’ feelin’ that Poindexter likes to convey.

So, here we have a trip from Front ‘O Town to Back ‘O Town, via the French Market, a fellow meeting up with a sassy and hardboiled Creole Girl, yeah, it’s a Happy Strut, playing the numbers 4-1-44 in a back alley, scoring some love potion Poindexter calls Muddy Dust, ending at momma’s place and devouring the one-of-a-kind mix of crawfish, alligator tails and spices and herbs and whatnot, Gumbo Filet. Can’t be beat. Poindexter calls the children home on alto and soprano, Booker Ervin wails, typically, like he’s a bluesman on the corner, as greasy a modernist as they came.

A good idea, this, working from a very personal experience, and played out joyfully and with swinging grit.

Listen to Gumbo on YouTube.