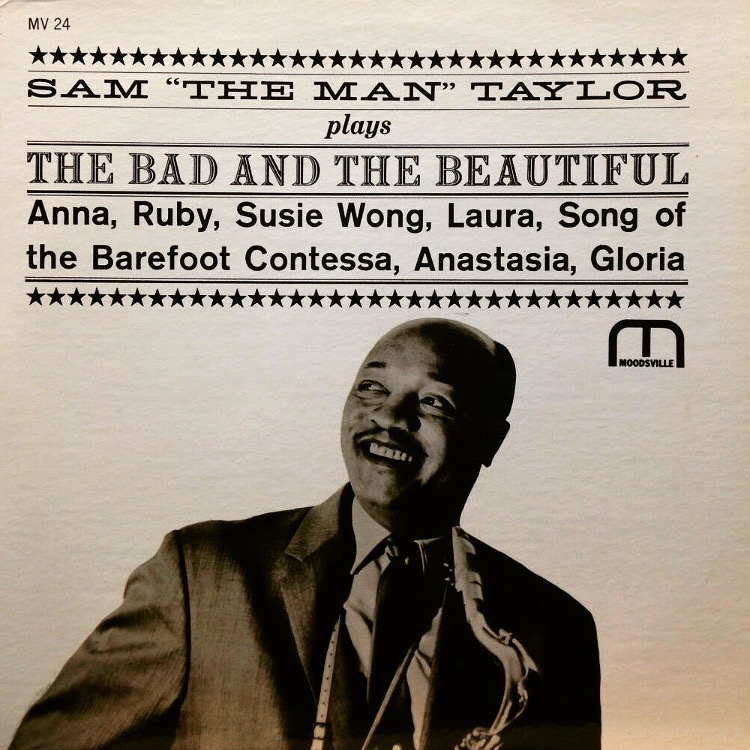

Sam “The Man” Taylor’s serenades to various dames are of the gutsy variety.

Personnel

Sam Taylor (tenor saxophone), Wally Richardson (guitar), Lloyd G. Mayers (piano), Art Davis (bass), Ed Shaughnessy (drums)

Recorded

on February 20, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as MV-24 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

The Bad And The Beautiful

Anna

Ruby

Suzy Wong

Side B:

Gloria

Laura

Anastacia

Song Of The Barefoot Contessa

You’ve heard him without perhaps knowing his name. Sam “The Man” Taylor was omnipresent in the rhythm and blues field, contributing lurid tenor sax to countless songs by artists on the Atlantic and Savoy labels, among those myriad Ruth Brown hits and Big Joe Turner’s Shake, Rattle & Roll, where “The Man”’s husky backing complemented the luscious lyrics “I’m like a one-eyed cat peepin’ in a seafood store / Well I can look at you till you ain’t no child no more” …

Lexington, Tennessee-born Taylor was the kind of musician that took different turns on the roundabout of black music. He played in the bands of Lucky Millinder, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles and Buddy (not Budd) Johnson. From the mid-50s to the mid-60s, Taylor recorded a string of both commercial and jazz records, the former bearing titles as Rockin Sax & Rollin’ Organ, Blue Mist, More Blue Mist and, hell why not, Mist Of The Orient. The latter included Jazz For Commuters, a satisfying swing record with Thad and Hank Jones, Budd (not Buddy) Johnson and Milt Hinton. In a fortunate and curious turn of events, Taylor became very popular in Japan in the 70s, recording albums like Hit Melodies From Shi Retoko To Nagasaki. Sayonara, Sam.

Prestige/Moodsville, in the guise of the clever A&R man Esmond Edwards, coupled Taylor with guitarist Wally Richardson, pianist Lloyd G. Mayers, bassist Art Davis and drummer Ed Shaughnessy. The result was The Bad And The Beautiful, an accessible record of show tunes that center around the luscious sax playing of Taylor, whose in-your-face strong sound, distinctive note-bending wails and meticulously calculated honk sequences are thoroughly entertaining. Good-old fashioned arpeggios link his breathy introductions to restrained climaxes.

Some may argue that Taylor’s style is built on gimmicks. I feel Taylor’s trick bag is the essence of his “people’s art”. It’s his characteristic bag and I think it would benefit the playing of many serious contemporary saxophonists if they’d pull some witty tricks out of it. There’s nothing in his playing, which strives for the middle ground between Ben Webster and Coleman Hawkins, that reeks of cheap sensationalism. Besides, “The Man” has some awfully nasty, bouncing licks to offer.

The Bad And The Beautiful contains a number of excellent ballads, notably the meaty Gloria and the blues-inflected Ruby. Anna swings Caribbean-style, The Barefoot Contessa bounces merrily. Nothing wrong with a “commercial” record that features a smooth and killer jazz band, suave and to-the-point guitar lines and, best of all, a couple of sublimely timed descending bass figures by the great Art Davis that silence The Bad and overwhelm The Beautiful.

Sam Taylor passed away in 1990.