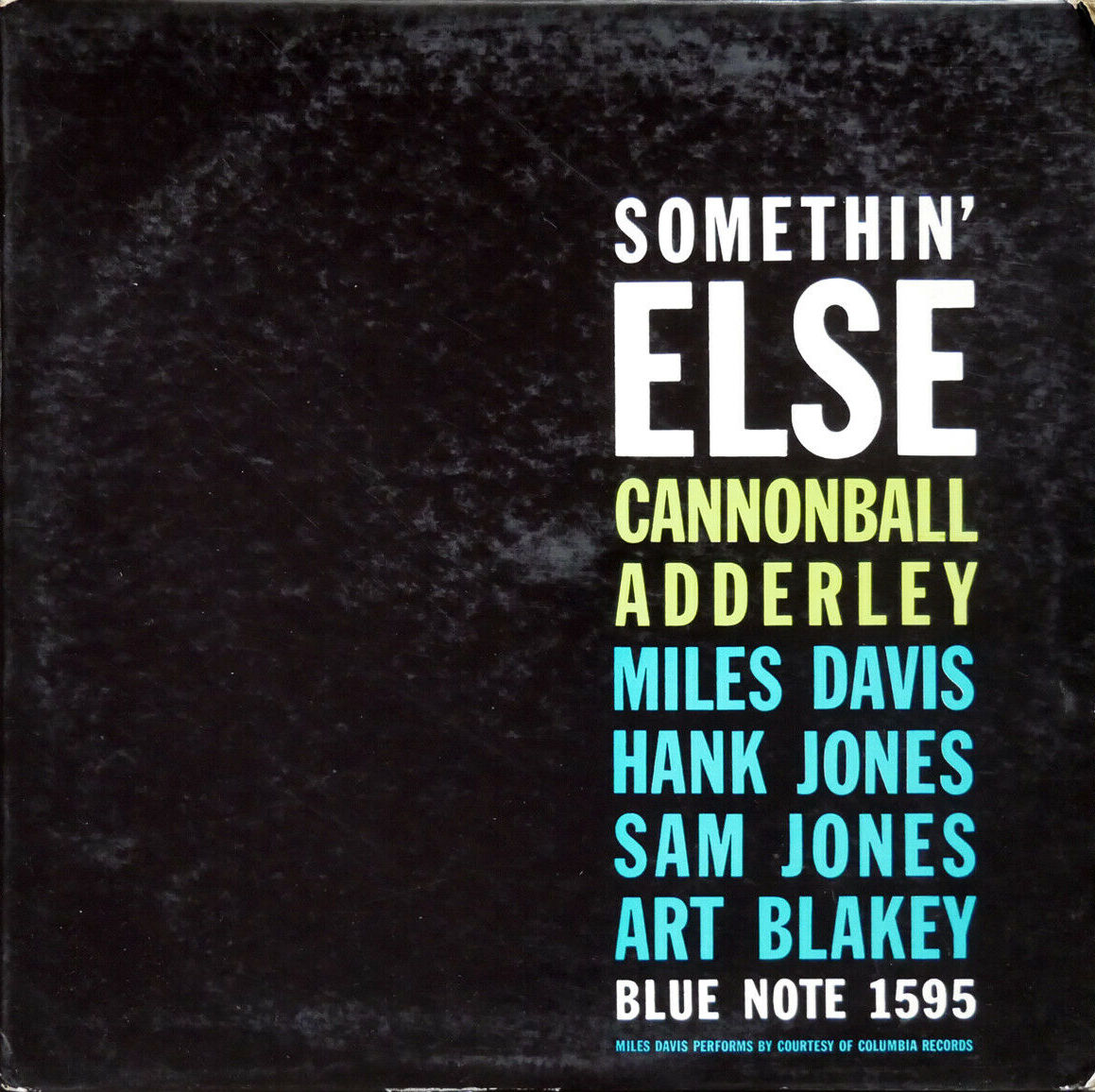

Can’t you hear those rustling autumn leaves?

Personnel

Cannonball Adderley (alto saxophone), Miles Davis (trumpet), Hank Jones (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Art Blakey (drums)

Recorded

on March 9, 1958 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 1595 in 1958

Track listing

Side A:

Autumn Leaves

Love For Sale

Side B:

Somethin’ Else

One For Daddy-O

Dancing In The Dark

Hyperbole may not be a strictly postmodern disease – as a matter of fact it all kind of started with the headlines in the Hearst papers in the 1930’s – but it is prevalent in the contemporary media-saturated society, excepting serious journalism. Perhaps I’m not entirely free from guilt. Most of us have our personal favorites that are in dire need of canonization. We live in a world of so-called ‘classic’ records. However, few records were instant classics in their lifetime. For instance and for various reasons, Duke Ellington’s Ellington At Newport (on the strength of the stellar 27 choruses of Paul Gonsalves during Diminuendo In Blue), Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz, Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder, Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters and Pat Metheny’s Still Life (Talking) are regarded as bonafide classics nowadays and though they were recognized as special back then, there was some lag time involved. Usually, as far as game-changing art goes, the dust needs to settle down. No doubt, it needed to settle down in Ornette Coleman’s case.

Cannonball Adderley’s Somethin’ Else is a classic record, one of those “100 must-hear records”. It also arguably is, like Ellington’s Newport and Morgan’s The Sidewinder, a classic on the strength of one tune, Autumn Leaves. In its time, it was regarded as exceptional. A.B. Spellman typified it as “near perfect”, a record with “not a wrong note nor throwaway song in its grooves.” That, regardless of the sublime highlight Autumn Leaves, is very true. One of the great things about Somethin’ Else, which paired Cannonball Adderley with Miles Davis, Hank Jones, Sam Jones and Art Blakey, is the consistent high quality of playing and a vibe all of its own. Hard to describe, easy to feel. Organic.

Big boost for Cannonball. The alto saxophonist from Tampa, Florida had joined Miles Davis in 1957, favoring the request of the Dark Prince over the invitation from Dizzy Gillespie. He had disbanded his quintet with Nat Adderley, who did not begrudge his big brother’s decision. After all, their stint in the roster of EmArcy had not been a financial pleasure. Cannonball was frustrated by EmArcy’s lack of support.

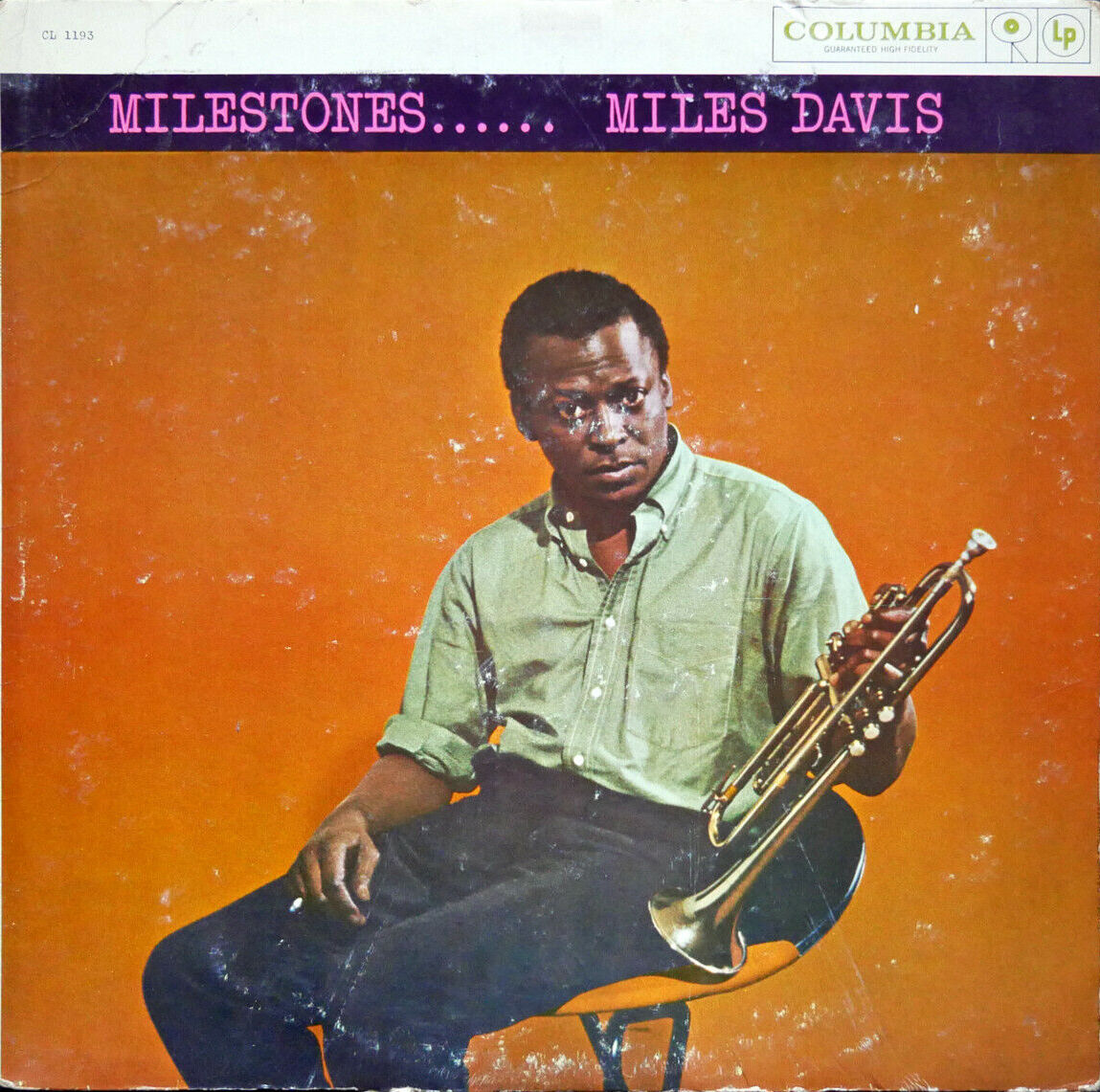

Not only was financial security and musical interaction with Miles Davis a boost, the pairing with John Coltrane, who had returned to Davis’ group after kicking the habit, proved influential for Cannonball. Following a series of performances that enabled Cannonball and Coltrane to perfect their ensembles and indulge in spirited battles, the band record the eponymous Milestones in February and March – March 4 saw Cannonball contributing to Dr. Jekyll and Sid’s Ahead. Afterwards, Cannonball hurried to Bell Sound Studio to fulfill his obligations to EmArcy and record Cannonball’s Sharpshooters. Busy day. Then came March 9 and Somethin’ Else. Busy week. This period eventually was a stepping stone to the Miles Davis masterpiece Kind Of Blue in 1959. And 1959 was the year that Cannonball signed with Riverside. His association with the emphatic label boss Orrin Keepnews reunited the Adderley brothers and gave the genial alto saxophonist the widespread recognition that he so well deserved.

So yeah, Somethin’ Else. Somethin’ else… Ain’t that the truth. Lovely vibe. It seems Cannonball was thoroughly affected by Miles Davis, maestro of economy and restraint, sideman on this date but omnipresent and the one that allegedly turned on Alfred Lion to the idea of recording Cannonball – “Is this what you wanted, Alfred?” is the raspy voice of Davis coming through the mic at the end of the title track. Davis had found a good mate in Hank Jones, Mr. Elegance, who hadn’t recorded with the trumpeter since a 1947 Aladdin session of Coleman Hawkins. And Blakey’s adjustment to Davis is sensitive, while not without steadily increased intensity. Balance and propulsion.

It was a great idea to contrast Davis’s handling of some of the melodies – muted lyricism – with the ebullient and unrestrained variations of Cannonball – delicious side streets and blues-drenched note-bending. How everyone is focused on the big picture, all nuance, delicacy and seemingly casual, lightly spicy swing, is marvelous. This is the overriding asset of the title track, which boasts swell interplay between Davis and Cannonball, the Nat Adderley 12-bar blues One For Daddy-O and the ballad Dancing In The Dark, which puts the leader in the limelight.

Autumn Leaves is every jazz musician’s wet dream. Everybody had a hard year. Everybody had a good time. Everybody had a wet dream. Everybody saw the sunshine. And everybody with an ounce of feeling in his gut feels the autumn leaves falling. This tune is the essence of the feeling that you want to present as a gift to the listener. You want the invited to succumb to a dream state and these guys are the combined epitome of transmogrification. They make sure that you softly land on a cloud. No, not even land. You are weightless, float in space.

Autumn Leaves hadn’t been interpreted in this way before and the idea of weightlessness is likely what was intuitively brought in by Miles Davis, who at the time was inspired by Ahmad Jamal, harbinger of seemingly ephemeral but meaningful harmonies. A five-note piano-bass intro is the bedrock for a dramatic Spanish-tinged brass and reed introduction, starting point for the plaintive melody by Miles Davis, underscored by Blakey’s subtle brushes. You feel satin cloth. Hear mice nibble. Then there’s Cannonball’s sermon, a merging of sleaze and clarity. Wonderfully dynamic. Of many colors, in the slipstream of Davis. Blakey switches to snappy sticks, till the return of Davis, who makes his mark with an extreme minimum of notes, one magenta, one pigeon grey, one slightly left from crimson. Hank Jones is last in line, and Mr. Elegance also prefigures the recurrent five-note figure with a stately a-capella bit. Lastly, the tune ends on a steadily slower tempo, Jones jingling modestly, Davis putting in a few cautious notes. Briefly, you savor the mystery of nature, are at peace with mortality… the autumn leaves gently fall on moss, fungi, kipple.

You don’t want it to end.