Mike LeDonne’s love affair with the organ goes back to his childhood. “I love to make people dance. Well, at least make them feel like dancing.

For a hard-working jazz musician from New York that has just finished a tightly scheduled tour in The Netherlands and Germany, Mike LeDonne (62) looks remarkably sprightly. His prickly grey beard underlines clear brown eyes. The baritone voice signifies warmth, the smooth flow of his speech plenty of confidence. Aside from his acclaimed career as a pianist and organist, LeDonne runs the Disability Pride Parade, raising funds and creating awareness for the cause of the disabled in the USA. The benefit was inspired five years ago by Mary, LeDonne’s daughter, who is non-verbal and legally blind. LeDonne speaks about her candidly and affectionately.

LeDonne, modern-day piano master who worked with legends such as Milt Jackson, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Golson, Benny Goodman, Sonny Rollins and Dizzy Gillespie, sustains a career as both pianist and organist. LeDonne’s Groover Quartet – including the alternating line up of Eric Alexander, Vincent Herring, Peter Bernstein and Joe Farnsworth – has been enjoying a residency of 15 years at New York City’s club Smoke. A remarkable feat, considering the required differing approach of playing acoustic piano and the electric, tone-wheel-driven Hammond B3 organ.

LeDonne talks about the beginning of his fascination with the organ and funky music while hanging out endlessly at the music store of his father in Bridgeport, Connecticut, how Brother Jack McDuff inspired him to add the organ to his professional life, about heroes like Wild Bill Davis and Don Patterson and some of the organ jazz records that inspired LeDonne to fulfill his calling as premier jazz organist.

FM: “When did you start playing organ?”

MLD: “My father was a jazz musician and he owned a music store. He had a lot of classic jazz records and organ jazz records. I loved the sound of the organ. I listened to Tower Of Power, who had Chester Thompson on organ, Sly Stone and James Brown. Sly and James Brown played organ too, of course! I started out on the Farfisa organ when I was 10. I had a little band going. We did gigs. And we rehearsed in the basement of my father’s store. That’s how I got seriously hooked on making music. One summer a crowd of neighborhood kids were dancing in front of the window. That felt so good! It got me thinking, ‘this is what I wanna do, make people dance!’ As a matter of fact, that’s still how I feel. I love to make people dance. Well, at least make them ‘feel’ like dancing.”

FM: “You grew up in Bridgeport, Connecticut. What was it like?”

MLD: “It was an industrial town and benefited from the World War II industry. But in the fifties, urban renewal passed by Bridgeport. It had good neighborhoods, but pretty funky parts as well. I loved it. There were a lot of clubs and good r&b bands.”

FM: “Sounds like a good breeding ground for soul jazz.”

MLD: “I don’t like that term. It’s about the commercial side. It’s patronizing for all-round, hard-working musicians. All jazz is soul jazz. But I do understand what it tries to convey. It’s about music that comes from experience. In my case, instead of playing How High The Moon, I’ll play Natalie Cole’s This Will Be An Everlasting Love, because it is a great tune that I grew up with. At Smoke I’ll play Michael Jackson’s Rock With You. Our crowd is a mix of old and young. The youngsters know the tune and they go, ‘hey, I didn’t know jazz could be like this!’. I’ve instilled it with swing, of course. My music is underlined by the black American aesthetic. It’s hard to explain. A certain kind of soulfulness. I played with both Milt Jackson and Bobby Hutcherson. Two extremes of vibraphone playing, same aesthetic… It’s a kind of magic. It’s the feeling Miles Davis describes when he listened to Billy Eckstine’s band with Charlie Parker: ‘It gets all up inside your body’.”

FM: “The groove.”

MLD: “Yeah, groove causes energy, people are attracted to the rhythm. The hard rhythm is a first for me, either on piano or organ, then comes the melody, the solo’s, from there everything has to go up and up.”

FM: “The Groover Quartet – what’s in a name – has been playing at club Smoke for almost 15 years. Plenty of time to polish the pocket.”

MLD: “That’s right! We’re a bit like the Blue Note groups of lore that played together constantly, with the rhythm sections that swing like mad. What we’re doing is not going to re-invent the wheel, but playing together is almost like telepathy and people respond to that, I think.”

FM: “You first made a name for yourself on the piano, the organ came later on.”

MLD: “Brother Jack McDuff is the reason that I play organ at all. I had stopped playing organ in college. I had become your typical idiot college kid immersed in ‘complex’ piano stuff. Then I moved to New York. My friend Jim Snidero, the saxophonist, played with McDuff. He took me to a gig and told McDuff that I played organ. So Jack asked me to sit in. Oh my God! I hadn’t played organ in five years. On drums was the legendary organ jazz drummer, Joe Dukes. I played a blues and McDuff liked it. He said that I was a good organ player and urged me to pursue a career as an organist. You better listen to the man! So I went and bought a new organ. That was the beginning of my career in organ jazz.”

FM: “What’s your secret? I mean, the piano and organ require a very different touch and approach.”

MLD: “I’ve been doing it for so long, it just feel natural. There is a difference, of course. You don’t control the sound with your fingers on the organ, the power is built-in. The piano requires subtle muscle control and needs power. My touch is pretty percussive on the piano and I love to belt out the bass lines on the organ pedals. But at the same time the walking figures on the organ keyboard have to be relaxed to stay in tempo. I probably play incorrectly, because I’m self-taught on the rather complicated organ. You need about four brains to play it!”

FM: “There is such a lot of different stuff going on in your style, on recordings but live especially. The orchestral sweep of Wild Bill Davis, the bebop approach of Jimmy Smith and Don Patterson. And you go from whispers to clusters of crazy notes that make me think of what they infamously called Coltrane’s sheets of sound.”

MLD: “I love the whole history of styles. I’m fond of the orchestral approach of Wild Bill Davis, I love to shout! The other guy I have to give it up to as someone who inspired me to explore is Lonnie Smith. He covers all bases. That made me think, why not? Why get stuck in one bag? I think my life with my daughter also has something to do with that. I come from a humbler place. I serve the music and love to give the audience the whole gamut. It’s not easy, I can tell you that! It has taken a lot of practice and experience. You have to be fully committed if you want to, for instance, incorporate that full drawbar orchestral stuff into your playing. There’s no place to hide.”

FM: “Who are some of your other influences besides Jimmy Smith?”

MLD: “You mentioned Don Patterson. He’s the guy that Jimmy Smith said was the greatest new organist he’d heard. His run of Prestige records is fantastic. It’s a shame that those records aren’t properly re-issued. Patterson had a great understanding with drummer Billy James. That was a unique combination. Patterson is underrated, he really was an innovator. He did things like crossing over the left hand while the right played the melody. The left might be switching chords around or even flutter a chord, a weird effect. I love that stuff. It’s churchy in a way, it has that black American aesthetic I mentioned earlier.”

“I love Melvin Rhyne. He probably was the greatest bebop organ player of all time. He was Milt Jackson’s favorite organist. And Milt didn’t like the organ! Rhyne doesn’t wham you in the head. He’s a horn-like player, stays in the middle register. His sound is dry. He’s all about substance. A big influence on me. I love Charles Earland. I heard his records on the radio but that was nothing compared to Earland live. I became a complete devotee. I once saw Brother Jack McDuff, Jimmy McGriff and Charles Earland on the same bill. McDuff and McGriff were in their prime and they were swinging their butts of, believe me. But I have to say, the swing of Earland was of another level. He belted out that bass line. My bass line is primarily influenced by Charles Earland. I like that heavy, in-the-pocket line.”

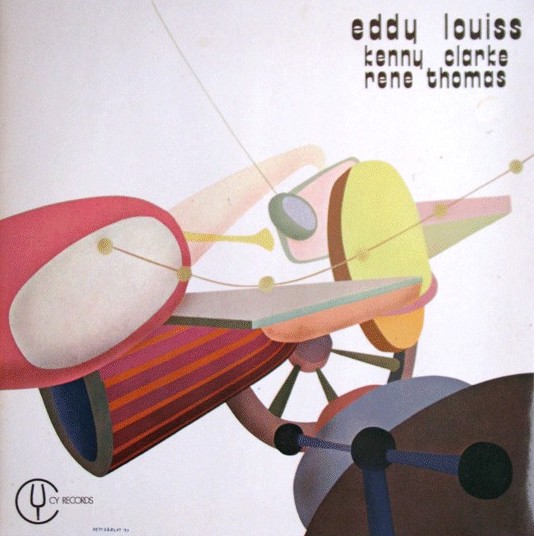

FM: “What are your favorite organ jazz records?”

MLD: “Let me think, there are a lot of them. The Prestige records of Don Patterson are high on the list. Wild Bill Davis and Johnny Hodges did tons of great stuff. And the way Davis plays on Blues For New Orleans from Duke Ellington’s New Orleans Suite record is fantastic. He was also a great accompanist of singers. That blues record with Ella Fitzgerald (These Are The Blues, FM) is great. Man, Wild Bill Davis was such a deep artist. Much more than just a good-time big band guy.”

“There’s Jimmy Smith of course. The record that hooked me as a kid was Live At The Village Gate. To me, I Got A Woman and The Champ sounded like they came from a James Brown record! The sounds he got out of the organ intrigued me. I spent hours figuring them out.”

FM: “You played with the late Grady Tate, who was featured on many of Jimmy Smith’s albums.”

MLD: “Yes. Fantastic drummer. By the way, I also had a steady gig with saxophonist Percy France.”

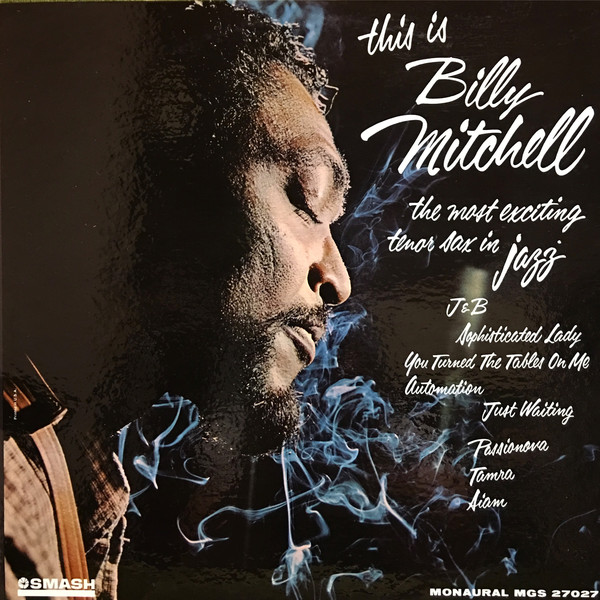

FM: From the Home Cookin’ album.

MLD: “That’s the one.”

FM: “Really? Jazz fans have always wondered what happened to him after his sole performance on that album.”

MLD: “A great player, not just a groover. He was a hip harmonist and great bebop player. I played with him many times in New York. He had a stroke of ridiculous bad luck. France suffered from cancer but recovered. Then, in a twisted turn of events, he got hit by a car and passed away.”

FM: That’s very tragic.”

MLD: “Yes, it is.”

Mike LeDonne

One of the most talented pianists and organists of his generation, Mike LeDonne (62) has worked with a who’s who of legends and contemporary class acts as Eric Alexander, Peter Bernstein, Ron Carter, Doc Cheatham, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie, George Coleman, Benny Golson, Benny Goodman, Tom Harrell, Bobby Hutcherson, Milt Jackson, Hank Jones, Sonny Rollins, Stanley Turrentine and Cedar Walton. He’s on more than 100 albums as a sideman and has recorded prolifically as a leader since 1988. The Groover Quartet documents LeDonne’s lifelong fascination with the Hammond organ. LeDonne has teached at Juilliard School Of Music and is one of the founders of the Jazz For Teen program in Newark, New Jersey.

Selected discography:

As a leader:

‘Bout Time (Criss Cross 1988)

To Each His Own (Double Time 1998)

Smokin’ Out Loud (Savant 2004)

The Groover (with The Groover Quartet – Savant 2009)

From The Heart (with The Groover Quartet – Savant 2018)

As a sideman:

Milt Jackson, Sa Va Bella (Qwest 1997)

Benny Golson, Remembering Clifford (Milestone 1998)

Gary Smulyan, The Real Deal (Reservoir 2002)

Jim Snidero, Tippin’ (Savant 2007)

Cory Weeds, Condition Blue: The Music Of Jackie McLean (Cellar Live 2014)

Go to the website of Mike LeDonne here.

Read about Disability Pride Parade here.