FLOPHOUSE FAVORITES 2016: Heaven abides, a year without ‘epic’ hypes. Let’s just go about our business and check out the real deal of the past, and present. In Cannonball’s words: ‘I mean soul, you know what I mean, soul.’ Read all about Flophouse Magazine’s favorite releases of 2016 below:

Cannonball Adderley, One For Daddy-O – Jazz At The Concertgebouw (Dutch Jazz Archive Series)

The Dutch Jazz Archive has been releasing the

Jazz At The Concertgebouw series since 2007. From the mid-fifties to the early sixties, the concerts presented the first opportunity for Dutch jazz fans to see and hear legends of jazz perform in person. Over the years, the Concertgebouw concerts have acquired a near-mythic status, much like the Kralingen Pop Festival gained a reputation as the Dutch equivalent of Woodstock for the babyboom hippies. Among other CD’s, the Dutch Jazz Archive released Concertgebouw performances by Chet Baker, The Miles Davis Quintet featuring John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers featuring Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter, Count Basie, J.J. Johnson, Gerry Mulligan and Lee Konitz/Zoot Sims. The latest addition highlights Cannonball Adderley, who played at Amsterdam’s prime concert hall on November 19, 1960. 1960 was a pivotal year for Adderley. The heavy-set, amiable alto saxophonist, who had made such an indelible impression upon his arrival in New York City in 1955, had really gotten his act together now, having signed with Orrin Keepnews’ Riverside label, which released the highly succesful and influential live album

The Cannonball Adderley Quintet In San Francisco at the tail end of 1959. Adderley brings the quintet with him, minus pianist Bobby Timmons, who’d returned to Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and was replaced by the English pianist Victor Feldman. Feldman’s

Exodus is performed, as well as

This Here,

One For Daddy-O and

Bohemia After Dark. Feldman makes his simultaneously sophisticated and bluesy mark in the Bobby Timmons chart hit,

This Here, Nat Adderley is ebullient and the rhythm section of Louis Hayes and Sam Jones makes abundantly clear why it was regarded as one of the hardest swinging outfits around. Cannonball is in top form, tackling the tunes like a lion grabbing the neck of a lion cub. Added to these four tunes is a guest performance of Cannonball Adderley with the local crew of pianist Pim Jacobs, guitarist Wim Overgaauw, bassist Ruud Jacobs and drummer Cees See at Theater Bellevue in Amsterdam on June 3, 1966. It was recorded for Dutch radio broadcast. The group, albeit in excellent command of the material, is a bit timid in contrast with Cannonball, who fires on all cylinders, occasionally flying off the rails with great zest. While jubilant, it seems Cannonball also had to drive out some demons that particular day in the nation’s capital.

One For Daddy-O – Jazz At The Concertgebouw comes with insightful liner notes by journalist Bert Vuijsje.

Find One For Daddy-O – Jazz At The Concertgebouw here.

Tom Harrell, Something Gold, Something Blue (HighNote)

At the age of 70, trumpet and flugelhorn player Tom Harrell is not about to slow down. Harrell, a supreme lyrical player and sophisticated composer, started out his professional career with Stan Kenton and Woody Herman in the late sixties and early seventies, had extended performance and recording stints with Horace Silver (1973-77) and Phil Woods (1983-89) and cooperated with numerous greats of jazz like Bill Evans, Dizzy Gillespie, Lee Konitz and Art Farmer. Since the late eighties, Harrell has broadened his horizon by writing for large ensembles, big bands and orchestra, both jazz and classical, including his own Chamber Ensemble. His work has been recorded by luminaries as Ron Carter, Kenny Barron, Hank Jones and Charlie Haden. For over ten years, Harrell has kept a quintet going, occasionally switching sidemen. For his latest release,

Something Gold, Something Blue, the line-up consists of drummer Jonathan Blake, bass player Ugonna Okegwo, fellow trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and guitarist Charles Altura. Forefronting his trademark, marshmellow sound, a sound that embraces you like a blanket on a cold winter’s day, Harrell’s set switches from the intelligent, lithe groove of

View, the world music of

Delta Of The Nile, modal tendencies of

Trances to the ethereal

Travelin’, which showcases Harrell’s gift for exploring every corner of a melody. An enigmatic, intriguing performer on stage, Harrell’s time in the studio is also still well spent.

Find Something Gold, Something Blue here.

Liebman, Ineke, Laghina, Cavalli & Pinheiro, Is Seeing Believing? (Challenge)

Saxophist and flautist Dave Liebman, the musical equivalent of Sesame Street’s cookie monster, has done about everything from being part of the Miles Davis group in the early seventies to writing chamber music. Liebman has also been an expert educational writer and organiser. Among other endeavors, he founded the International Association Of Schools Of Jazz, stressing educational cooperation without borders. It’s this responsive spirit that’s at the heart of

Is Seeing Believing, a collaboration between the five IASS colleagues Liebman, veteran Dutch drummer Eric Ineke (a longtime Liebman associate who also played on, among others,

Lieb Plays The Beatles and

Lieb Plays Blues à la Trane), pianist Mário Laghina, bassist Massimo Cavalli and guitarist Ricardo Pinheiro. An international cast that cooks a varied brew. Excepting a robust interpretation of

Old Folks, marked by the vibes of John Coltrane’s Impulse output, courtesy of Liebman’s freewheeling, uplifting phrases and Ineke’s lush, pulled-and-pushed rhythm, and the Post Bop-meets-Gypsy-meets-Dixie-meets-Prog Pinheiro tune

Ditto, the repertoire is soft-hued, introspective, a gentle but stirring lake of intricate, fine-tuned jazz. A conversation between Liebman’s sensual soprano and Pinheiro’s spicy acoustic guitar is the centre of the warm-blooded piece of folk jazz,

Coração Vagabundo. On the other tunes, Pinheiro plays electric guitar, employing a prickly, Jim Hall-ish sound, and daring to turn into eccentric pathways during his concise stories. Like in the sprightly take of

Skylark, wherein Liebman and Pinheiro improvise simultaneously. With the wisdom of the elder master, Liebman’s tenor work is spirited without excessive frills. The highlight is the title track, a composition of slow-moving voicings that meander on the sensitive, resonant sound carpet of Ineke, which nicely lets the personalities of the soloists ring through. Pianist Mário Laghina’s embrace of the melody is enamouring, sometimes following the steps of Liebman, sometimes going against the grain teasingly. Part of an album of moving and intelligently crafted modern jazz.

Find Is Seeing Believing? here.

Woody Shaw & Louis Hayes, The Tour Volume One (HighNote)

Nowadays, trumpeter Woody Shaw is revered as the last great trumpet innovator. Following a low ebb at the turn of the decade, Shaw was at a creative peak in the mid-seventies. On a collision course with fusion and free jazz, the virtuoso Shaw candidly expressed the need to restore faith in straightforward, acoustic jazz, a need that equally passionate classic (hard) boppers such as Cedar Walton, Jimmy Heath, Joe Henderson, Barry Harris and Bobby Hutcherson undoubtly agreed with:

“I blame the musicians for nearly killing the music. I mean, some of the rubbish they call jazz in The States is not jazz.” And about the new group he founded with Louis Hayes in 1976:

“We said: ‘Wait a minute – we gotta change this a little bit. By no means is jazz dead – that’s essentially why Louis Hayes and I formed this band.” Boy, did Shaw deliver on his promise! In the past, High Note released a series of live recordings by Woody Shaw. This year, the label released

The Tour Volume 1, a live recording of his group in Stuttgart, Germany on March 22, 1976. It’s a cutting edge set that shouldn’t be missed. According to the famed jazz producer, writer and co-founder of Mosaic, Michael Cuscuna, who visited countless Woody Shaw shows in the seventies, the trumpeter was a constant crackerjack. Indeed, all the assets that make Shaw such a unique jazz artist are in check: his dark, rich tone, clean attack, facility in all registers, surprising effects and suave modulation through keys. And on the experimental side, the use of the (Coltrane-influenced) pentatonic scale and wider intervals. The kind of stuff that was difficult to pull off with the three-valved trumpet. The group’s no-holds-barred attitude shines through on all cuts: avant-leaning, burnin’ originals by Shaw, (

The Moontrane) Matthews, (

Ichi-Ban) and Larry Young (

Obsequious), a boiled-over bossa of Walter Booker/Cedar Walton (

Book’s Bossa) and a greasy semi-ballad of Peggy Stern (

Sun Bath). The ever-hard swinging Louis Hayes is relentless, Junior Cook holds his own with a bluesy, big-toned sound and ‘Trane-tinged, edgy phrasing and Ronnie Matthews contributes deft, ringing statements. The somewhat slower

Invitation, a Bronislaw Kaper composition, is a gas. Shaw is fluent like a slithering snake in the grass and his technical prowess isn’t executed for virtuosity’s sake, but instead facilitates a beautifully constructed, quietly thunderous storyline. A cat who was truly revealing the full potential of the trumpet.

Find The Tour Volume One here.

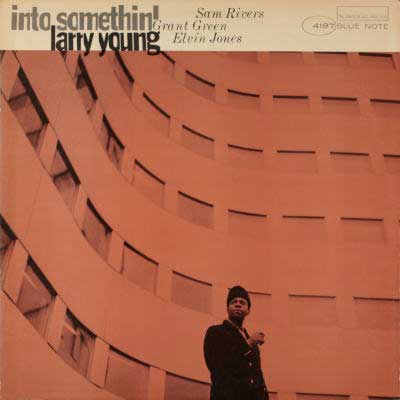

Larry Young, In Paris: The ORTF Recordings (Resonance)

Woody Shaw is present as well on the outstanding 2016 release by Resonance Records,

Larry Young – In Paris: The ORTF Recordings. It features sessions that were recorded for radio broadcasting during Young’s periodical 1964/65 sojourns in Paris. Larry Young took Hammond organ jazz beyond its churchy soul jazz roots and the bop ethos of Jimmy Smith, adding whole tone scales and the intervallic inventions of John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner to a clean, crisp sound and restrained, resonant phrasing. The result was a fresh and amazingly free-flowing kind of organ jazz. The organist, well-known for his role on Miles Davis’

Bitches Brew, returned to the USA at the end of 1965, where he released his acclaimed masterpiece

Unity. In Paris, Young was also joined by tenor saxophonist Nathan Davis and drummer Billy Brooks as well as an international parade of players, including tenor saxophonist Jean-Claude Forenbach. At a purposeful crossroads in his career, Young’s style alternates between the layered, wayward runs of

Trane Of Thought and ferocious, pentatonic variations on melodies of Wayne Shorter’s

Black Nile. The 19-year old Woody Shaw is a jubilant asset to tunes such as his original composition

Zoltan (that would be featured on

Unity), nicely contrasting with Nathan Davis’ earthy, edgy tenor.

In Paris, which was released on both CD and limited edition vinyl, is the kind of release of unearthed classic jazz material that makes your heart skip a bee: the sound quality is excellent, the package is top-notch and includes previously unreleased photographs and a vast collection of insightful, meticulous liner notes by, among others, Nathan Davis, organist Lonnie Smith, Woody Shaw III, Larry Young III and Resonance producer Zev Feldman. A rare treat for classic jazz fans and a mouth-watering dish for Hammond B3 geeks.

Find In Paris: The ORTF Recordings here.

Willie Jones III, Groundwork (WJ3)

Afusion of tradition and innovation, keeping it fresh, energetic,

real. The versatile drummer Willie Jones III, who worked with Horace Silver, Hank Jones, Herbie Hancock, Roy Hargrove and Arturo Sandoval, reserves his self-owned independent label, WJ3, for his hardest boppin’ efforts.

Groundwork, the seventh album of Jones on WJ3, is dedicated to his mentor, Cedar Walton, who passed away in 2013, and other deceased colleagues Ralph Penland, Mulgrew Miller and Dwayne Burno. It has the vibe of both the mid-sixties hard bop Blue Note albums and the early seventies catalogue of Muse and Mainstream, created by a mutually responsive outfit that includes veteran bassist Buster Williams (former Walton associate) and the outstanding pianist Eric Reed, who deceptively easily marries intricate modalities with lively blues bits. Post bop gems like the moody Cedar Walton tune

Hindsight and the uptempo cooker

Gitcha Shout On are alternated with a frolic Buster Williams blues,

Toku Do, and Latin-flavored tunes like Ralph Penland’s

Jamar and Reed’s

New Boundary. Repertoire that’s uplifted also by the pristine, quicksilver phrases of vibe player Warren Wolf and lively blowing of trumpeter Eddie Henderson and saxophonist Stacy Dillard. The propulsive drumming of Jones, just a pulse away from both Billy Higgins and Joe Chambers, is crucial to the proceedings, favoring sympatico support over solo time.

Dear Blue, a melancholy ballad written by the Dutch saxophonist Floriaan Wempe, ignites strong emotions. Stacy Dillard creeps into the crevices of the crepuscular melody, evoking memories of Chet Baker singing ballads later in life. Do you hear that pin drop?

Find Groundwork here.