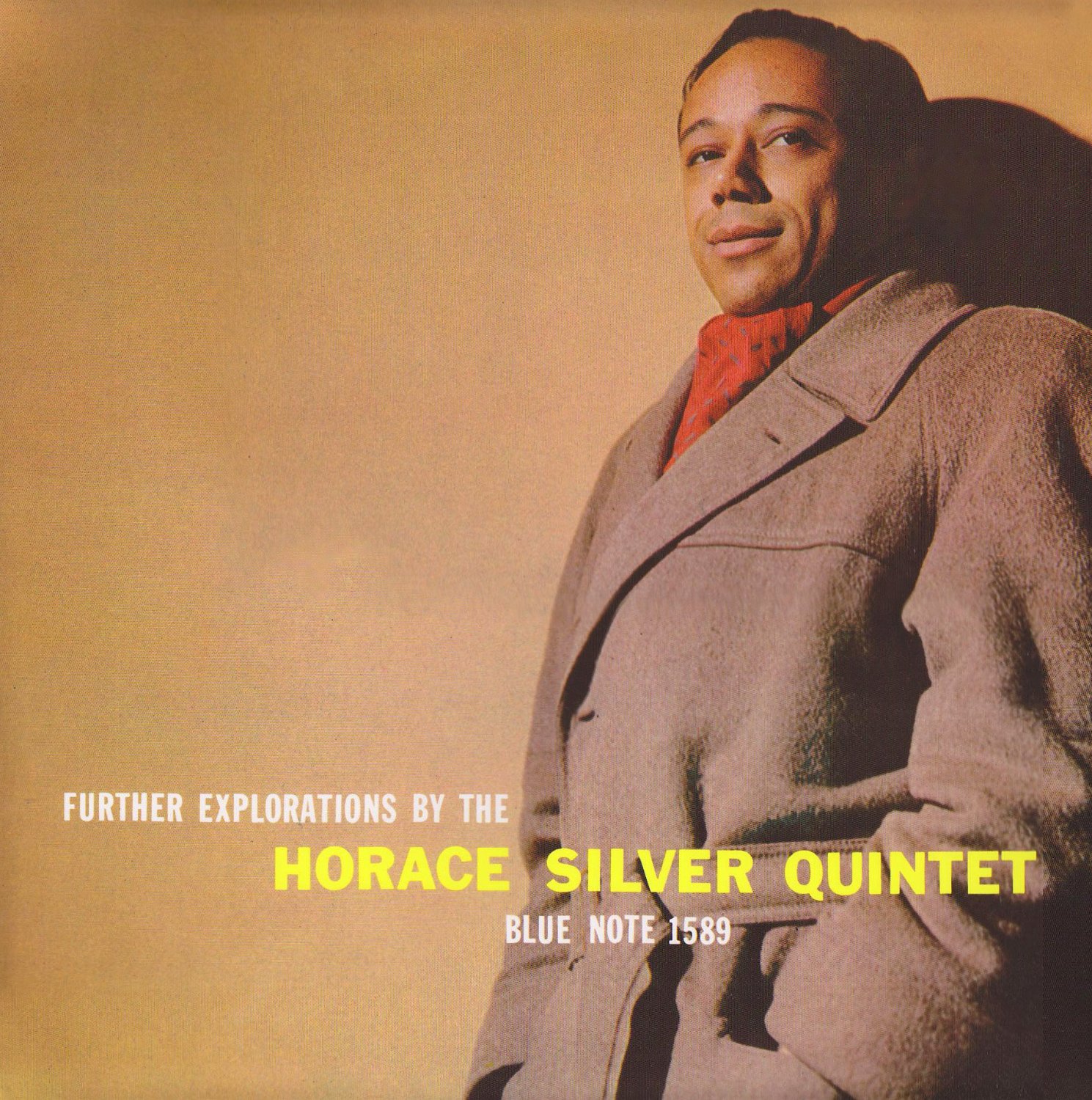

Further Explorations, pianist Horace Silver’s sixth release on Blue Note, is a revealing album in his catalogue. Silver branches out beyond his idiom, further developing tunes with Latin rhythm, the minor key and unusual bar lenghts. Carefully crafted but uncluttered, the album doesn’t stress the down-home feeling Horace Silver incorporated into modern jazz. But Silver’s innovative writing and supreme piano concept make it an extremely rewarding listening experience.

Personnel

Horace Silver (piano), Clifford Jordan (tenor saxophone), Art Farmer (trumpet), Teddy Kotick (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

Recorded

on January 13 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 1589 in 1958

Track listing

Side A:

The Outlaw

Melancholy Mood

Pyramid

Side B:

Moon Rays

Safari

Ill Wind

The album sits between Stylings Of Silver, which had the same line-up except Hank Mobley instead of Clifford Jordan, and the albums Silver made with his longstanding group from 1959 to 1964, consisting of Blue Mitchell, Junior Cook, Gene Taylor and Roy Brooks. The ensemble playing of the group on Further Explorations is outstanding. Art Farmer contributes elegant solos and his sound is crystalline. Clifford Jordan’s playing, albeit a bit guarded at times, is excellent.

The first two cuts make it clear that although Further Explorations is an appropriate title, More Stylings Of Silver would be on the money as well. The Outlaw has unusual bar lenghts, a Latin beat alternating with 4/4 time and labyrinthine stop-time sections, yet moves along swiftly in the manner of early Silver gems such as Room 608. (from Horace Silver And The Jazz Messengers) It’s intricate, but at the same time would still be a credible juke box tune.

The second composition, the ballad Melancholy Mood, is a change of mood indeed. It’s a ballad that starts as a warm-hearted duet between Silver and Teddy Kotick, (one of Charlie Parker’s favorite bass players) who plays bowed bass on the Thelonious Monkish-theme. Louis Hayes chimes in with smooth, elevating brushwork. Silver’s solo is a gem, mixing long stretches of brooding minor chords and notes with sensuous phrases and repeated funky licks.

Both Pyramid and Moon Rays have perplexing, yet swinging themes. Pyramid is a mix of a catchy melody, Latin tinges and stop-time choruses, wherein Art Farmer finds his way with lyrical, long flowing lines. Moon Rays is the eleven-minute long centre-piece of the album. As counts for all tunes, the melody, again partly Latin, is exasperatingly beautiful. The manner in which Silver’s occasional old-timey lines travel in twisted ways again proofs the influence of Thelonious Monk. The parts of Clifford Jordan and Art Farmer are proficient, but somehow fail to get on the magic bus of Silver’s inventive tune.

Jordan and Farmer are much better on Safari, a re-visit of the trio take Silver did with Art Blakey and Gene Ramey on his Blue Note debut Introducing The Horace Silver Trio in 1952. At breakneck speed, Clifford Jordan finally has gotten the real hot blues. Arlen and Koehler’s Ill Wind, the only non-Silver composition on the album, refers to Things Ain’t What They Used To Be with a couple of notes that Silver also uses in his interesting solo. Ill Wind is not the distinctive melody you’d dream up as an ending to the carefully prepared, wonderful set of Silver inventions that comprise Further Explorations.