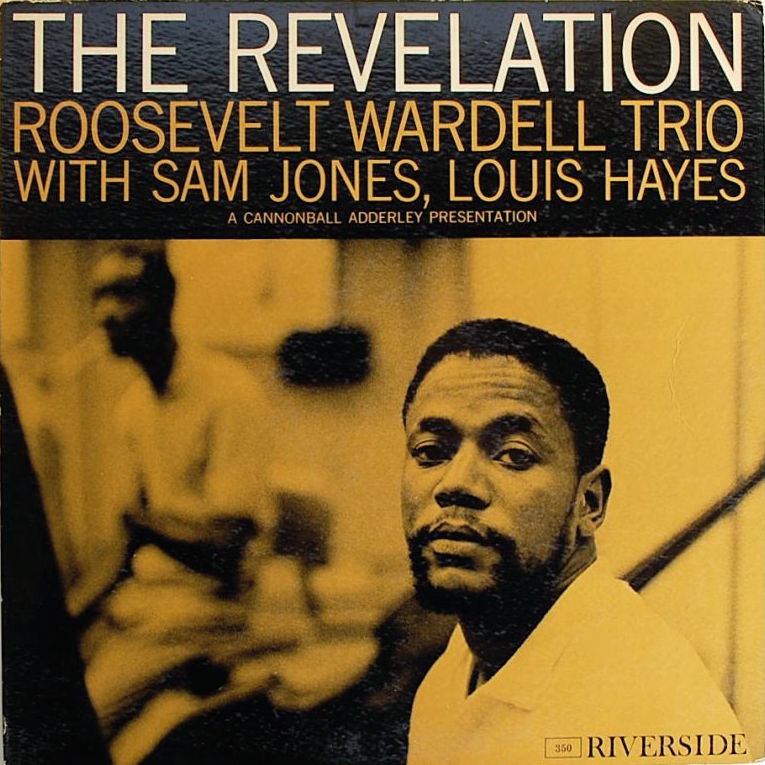

It really comes close to a revelation, the obscure Roosevelt Wardell’s only album as a leader, The Revelation. The work of a very original pianist which has been neglected for much too long.

Personnel

Roosevelt Wardell (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

Recorded

on October 5, 1960 at United Recording Studios, Los Angeles

Released

as RLP 350 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Like Someone In Love

Lazarus

Autumn In New York

Max The Maximum

Side B:

Elijah Is Here

Willow Weep For Me

Cherokee

The Revelation

The mystery remains. Info on the net close to nada. With the liner notes from Chris Albertson to go on, the following story is revealed: While Baltimore-born Roosevelt Wardell (1933 –1999) was playing jazz piano from an early age, he initially pursued a career as an r&b pianist and singer, accompanying others as well as recording a couple of singles as a leader. Wardell spent the first part of the fifties in the Army. As early as 1953, alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, while in the Army at Fort Knox, saw him play in Louisville, Kentucky, and occasionally thereafter. Said Cannonball: “He was more than adequate even then (…) and I sympathized with him as I did with all those who were basically jazzmen but were forced to play that way to make a living.” Cannonball got Wardell a place in the Army Band. Once out of service in 1955, Wardell subsequently played with Bull Moose Jackson, Max Roach and Joe Turner in 1957 and occasionally sat in with Cannonball’s group.

In 1960, Wardell played with Dexter Gordon in the on-stage band of the (in-)famous play The Connection. The Cannonball Adderley Quintet was in L.A. as well. (the Wardell date of October 5 preceded the quintet’s At The Lighthouse gig and album recording session of October 16) Adderley, who by then was not only recording artist but also A&R man for Orrin Keepnews and Bill Grauer’s Riverside label, responsible for a series of ‘Cannonball Adderley Presentation’-albums, seized the opportunity to record Roosevelt Wardell at United Recording Studio, engineered by Wally Heider. For the occasion, Roosevelt Wardell picked Cannonball’s tight-knit rhythm section of bassist Sam Jones and drummer Louis Hayes, a now legendary team that proved perfectly suitable for this job of blues-infested bop.

Mr. Wardell’s not the type of kid that lurks in the background. No fly on the wall. More like a stinging bee. Quite the attack! Like one of his greatest influences, Bud Powell, his touch is relentless. While the keys threaten to jump off the balcony, he continues to bring clarity of line, dashing off one dazzling run after the other. The pianist’s not to be overshadowed by the rumble of the crowd at the bar and loves to entertain as well, following up jolly tremolos with mean, stuttering blues riffs. Perhaps a residu from his chitlin’ circuit days. Yet, for all his swagger, Wardell’s modern jazz conception is a textbook example of intelligence and finesse.

Reminiscent of the diverse lot of Bud Powell, Carl Perkins, Ray Bryant, perhaps influenced by the orchestral brilliance of Art Tatum, Wardell nonetheless resides in a universe totally his own. While the pianist’s tasteful, muscular takes on a ballad – the Vernon Duke tune Autumn In New York – and a blues – Willow Weep For Me – satisfy the customer, the bop-inflected tunes are most arresting. The romantic opening cadenzas of Like Someone In Love are followed by a whirlwind of phrases that together comprise a staggering wall of sound, accompanied by meaty, stride-like bass lines. Cherokee’s percussive, chant-like beginning by the trio is very cool, the speedy, powerful story of Wardell leaves nothing to be desired. The Revelation, a tune written by his childhood friend Yusef Salim, is fast-paced badaaas bop.

Roosevelt Wardell wrote some nifty, blues and gospel-drenched tunes, based on familiar changes. Three were featured on The Revelation. Max The Maximum’s a funky little tune, a fast-paced chord progression interspersed with a tacky stop-time section. The notes that Wardell plays in the loping, mid-tempo Elijah Is Here tumble over one another like chipmunks over a little heap of chestnuts. Roosevelt Wardell could be likened to the original cats of modern literature, those singular personalities and stylists like Frederick Exley or Maarten Biesheuvel, whose deceptively messy, long and winding paragraphs always somehow land on their feet. Looks easy, isn’t. Wardell’s tale of Lazarus is high drama, a Speedy Gonzalez-exercise of I Got Rhythm-changes, the total sum of his solo seemingly consisting of one long, furious line. A kind of invention of a new genre perhaps best labeled as BEBOP ROCK.

The comments of Roosevelt Wardell comprise the anti-thesis of drama. About the session, the pianist level-headedly remarked: “Nice, very nice.” Too bad that Wardell disappeared into obscurity soon after and The Revelation remained the only album release the characteristic pianist commented on.

(The album is on Spotify on a twofer including Evans Bradshaw, scroll down for Roosevelt Wardell)