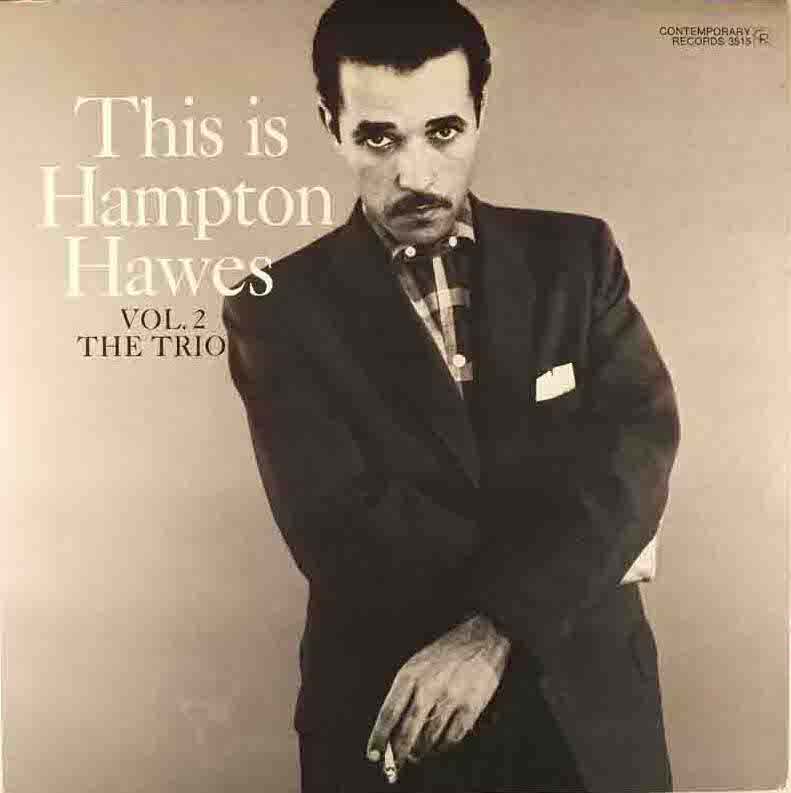

This, indeed, is Hampton Hawes. The coolest smokin’ cover. Immaculate, intense bebop. The pianist in full flight, a few years before the life of the addicted Hawes would take a tragic turn.

Personnel

Hampton Hawes (piano), Red Mitchell (bass), Chuck Thompson (drums)

Recorded

on December 3, 1955 and January 25, 1956 at Contemporary Studio, Los Angeles and June 28, 1955 at Los Angeles Police Academy, Chavez Ravine

Released

as C3515 in 1956

Track listing

Side A:

You And The Night And The Music

Stella By Starlight

Blues For Jacque

Yesterdays

Side B:

Steeplechase

Round About Midnight

Just Squeeze Me

Autumn In New York

Now here’s a pianist that warrants more copy than is usually dedicated to him. On par with likeminded players from the generation that followed Bud Powell, Hampton’s jail sentence from 1959 to 1963 was an obstacle to the road to recognition. The

vintage years of hard bop went by him, by and large. To name a few, Sonny Clark burnt bright, didn’t fade away, becoming one of the legends of jazz music after he tragically overdosed. Horace Silver

set the vintage years

in motion, delivering one catchy, clever tune after another. Red Garland’s claim to fame involved his stint with the First Great Miles Davis Quintet.

That is not to say that the playing of Hawes hasn’t find its way to jazz fans around the globe and to many contemporary musicians somehow. Neo-boppers, as expected. On the other side of the spectrum, there are fans like Matthew Shipp. And Ethan Iverson. Here’s what the eclectic pianist with the unwavering curiosity in and broad knowledge of the tradition and anything musically challenging has to say about Hawes: ‘Even though Hampton Hawes had a strong and urgent touch, there was always air around his lines. He seemed to breathe his bluesy bebop into the piano. Along with many others, Hawes took Bud Powell and Charlie Parker and blended it with the pastel colors found in California, although Hawes’ unpretentious virtuosity and perfect jazz beat stood out among his West Coast brethren.’

It is also not to say that Hawes isn’t, on some level, ‘famous’. Or, was. On the contrary. Hawes was born in Los Angeles in 1920 to a father that was a minister and a mother that was a church pianist of the Presbyterian Church. Like so many beboppers, he was seriously addicted to heroin. In 1958, undercover Feds arrested Hawes, white supremacy everywhere, the jazz musician a ‘degenerate evil to society’, who refused to snitch on fellow users and dealers. Hawes got an unbelievable 10-year sentence. In between his trial and sentence, the pianist recorded The Sermon, a telling reflection of the man’s fear, desperation, and what seemed idle hope of better days. Regardless, during his third year in jail, seeing the new President in office, the good looking, emphatic John F. Kennedy, Hawes decided to request for a pardon. Lo and behold, as one of very few, a mere 43 that year, he was released by JFK in 1963.

Mr. Hawes subsequently reaped what he sowed, playing to admiring crowds in Europe and Asia, deepening his modern jazz conception on, for instance, superb Enja albums, and delving into electronic (Fender Rhodes) playing in the process. His biography Raise Up Off Me, published in 1974, is classic jazz literature, perhaps best likened to Art Pepper’s Straight Life. Hawes passed away untimely in 1977.

Hawes’ series of Contemporary albums in the mid-and late fifties are among the period’s finest bop and hard bop releases, not least the All Night Session Volume 1-3 live LP’s. Hawes began the series in 1955 with his debut The Trio Volume 1. His second album This Is Hampton Hawes, recorded in December 1955 and January 1956, is subtitled The Trio Volume 2. Same trio – Hawes, bassist Red Mitchell, drummer Chuck Thompson – same procedures: a remarkably fresh, original take on standards, ballads, blues and a few self-penned compositions. The latter’s list consists of You And The Night And The Music, Stella By Starlight, Yesterdays, Autumn In New York, Monk’s Round About Midnight, Parker’s Steeplechase, Duke Ellington’s Just Squeeze Me and the Hawes composition, Blues For Jacque.

Like the masters of bop, Charlie Parker and Bud Powell, often Hawes is pure energy, dashing off streams of notes that dart this way, that way, seldom ending up in a rot, instead tied together in bundles that reveal the quickest harmonic mind. Long, spirited sentences. Immaculate pace. The gospel, so prevalent in his youth, is definitely under the surface of a style that is carried out with a decisive touch, the touch of a carpenter with a passion for the craft. Bits of bebop’s mid-and post-war angst, the cultish, dedicated stress on beauty and sophistication as the antidote to the black man’s struggle still shining through. But never, like the less talented players, panicky. As Iverson says: air. In a sense, Hawes might be called one of few players who played the Bud Powell stuff that, because of his mental problems, Bud Powell himself wasn’t able to anymore in the post bop era.

The piano as a horn. Hawes blows, his refreshing breeze and gusty winds are still fresh after all these years.