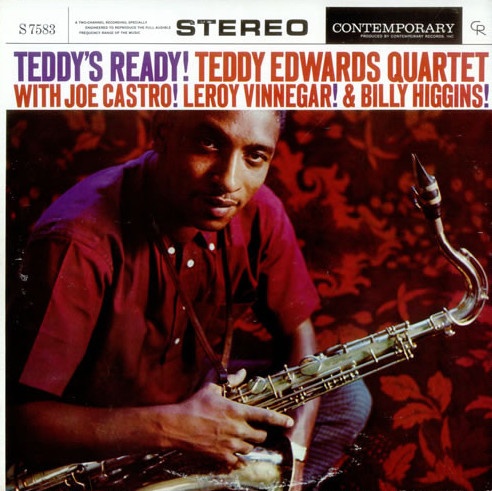

And we’re ready for Teddy. By 1960, tenor saxophonist and bebop pioneer Teddy Edwards had settled firmly into his role as prime straightforward player and delivered the excellent Teddy’s Ready for the Contemporary label on the West Coast.

Personnel

Teddy Edwards (tenor saxophone), Joe Castro (piano), Leroy Vinegar (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded

on August 17, 1960 at Contemporary Studio, Los Angeles

Released

as Contemporary 3583 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Blues In G

Scrapple From The Apple

What’s New

You Name It

Side B:

Take The “A” Train

The Sermon

Higgins’ Hideaway

The West Coast, Los Angeles to be precise, is where the Jackson, Mississippi-born Edwards had settled in the mid-40s. Edwards made his mark with the 1947 The Duel recordings with Dexter Gordon. Like Gordon, who also lived west at that time, and Hampton Hawes, Howard McGhee, Elmo Hope, Edwards stood out as the edgy, hard-driving player among the cool Californian musicians. Around 1960, Edwards was on a hot streak. Preceding Teddy’s Ready, which was recorded on August 17, 1960, Edwards released It’s About Time, a killer session with the greasy Les McCann trio, and Sunset Eyes, a fine date that boasts the title track, the Edwards composition that became somewhat of an instant standard. Both albums were released on Pacific Jazz. Subsequent recordings were Together Again, a reunion with bop mate, trumpeter Howard McGhee and Good Gravy, released in 1961, which also comes highly recommended.

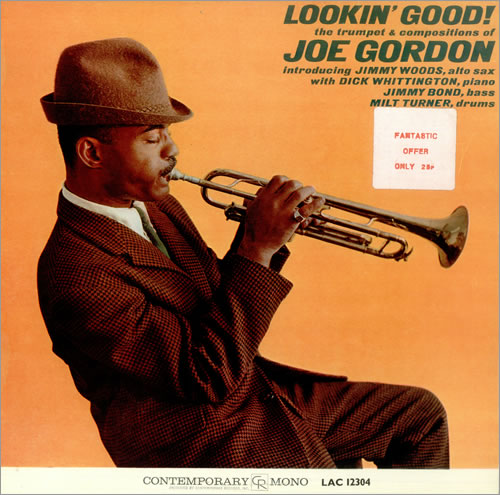

Teddy’s Ready (Together Again and Good Gravy as well) was released on Contemporary. So in comes engineer Roy DuNann, lesser-known than Rudy van Gelder but equally revered by diehard classic jazz fans, with a crisp and clear sound canvas, punchy overall group sound, and precisely audible details. A kind of lightweight vibe that totally brings out the group’s swing, the way a master stylist makes prettier a pretty girl, not with theatrics but with subtle shadings of the beaut’s personality. This group is swinging subtly but driving. It consists of: Billy Higgins, equally at home in hard bop and – he was part of Ornette Coleman’s group – free jazz surroundings, Leroy Vinegar, in-demand all-rounder with an uncanny ability to walk and Joe Castro, relatively unknown, talented West Coast-based pianist who also made the sought-after Groove Funk Soul album on Atlantic with this Teddy Edwards group.

Who needs another horn? Not me. Not Teddy. It is, in fact, a blessing that Edwards carries Teddy’s Ready (and Good Gravy) on his own. No distractors, just Teddy Edwards, flying on the wings of the trio’s nightingale, focusing on the smoky story to tell. The voluptuous, slightly husky sound of Edwards is the tenor sax tone equivalent of the Montechristo #2 cigar, contraband from Cuba, fired up with a rusty Zip lighter. There is a minimum of strain between his lips, facial muscles, breathing, and the sound that emanates from his horn. Like every serious jazz musician, Edwards must’ve worked hard, I mean, hard, at ending up with a personal tone yet, like every great jazz musician, the completely natural flow suggests it was a cinch. Why do we rarely hear tones like these, these days? Perhaps because jazz has changed along the lines that the world has changed? It’s flophouse vs zero tolerance, Bull Durham vs e-cigs. Obviously, more to the point, the classic saxophonists acquired certain techniques that enabled them to override the buzz of the crowd in the dingy jazz club, which carried no amplification.

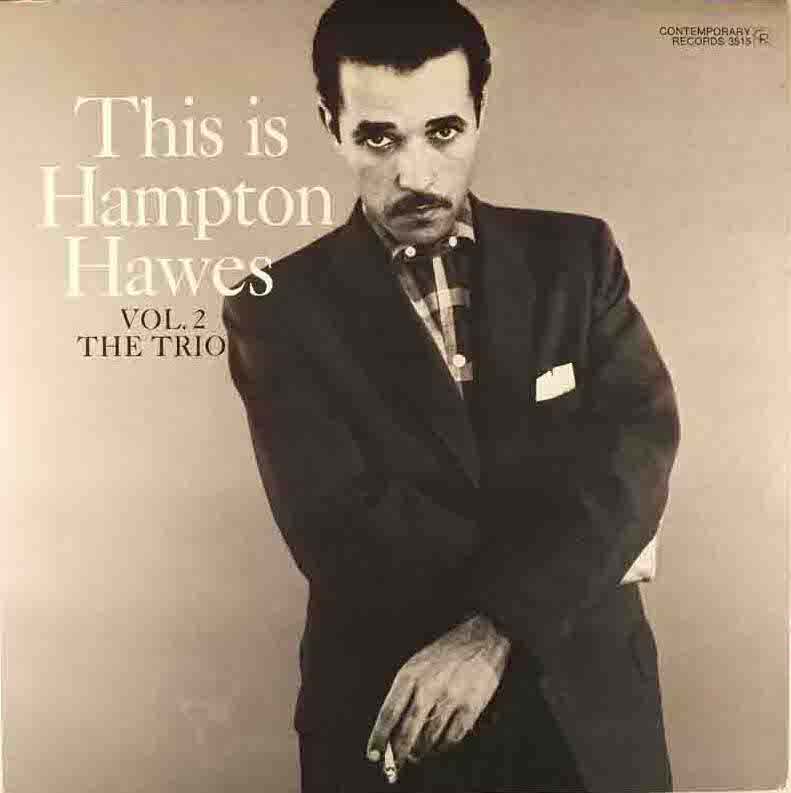

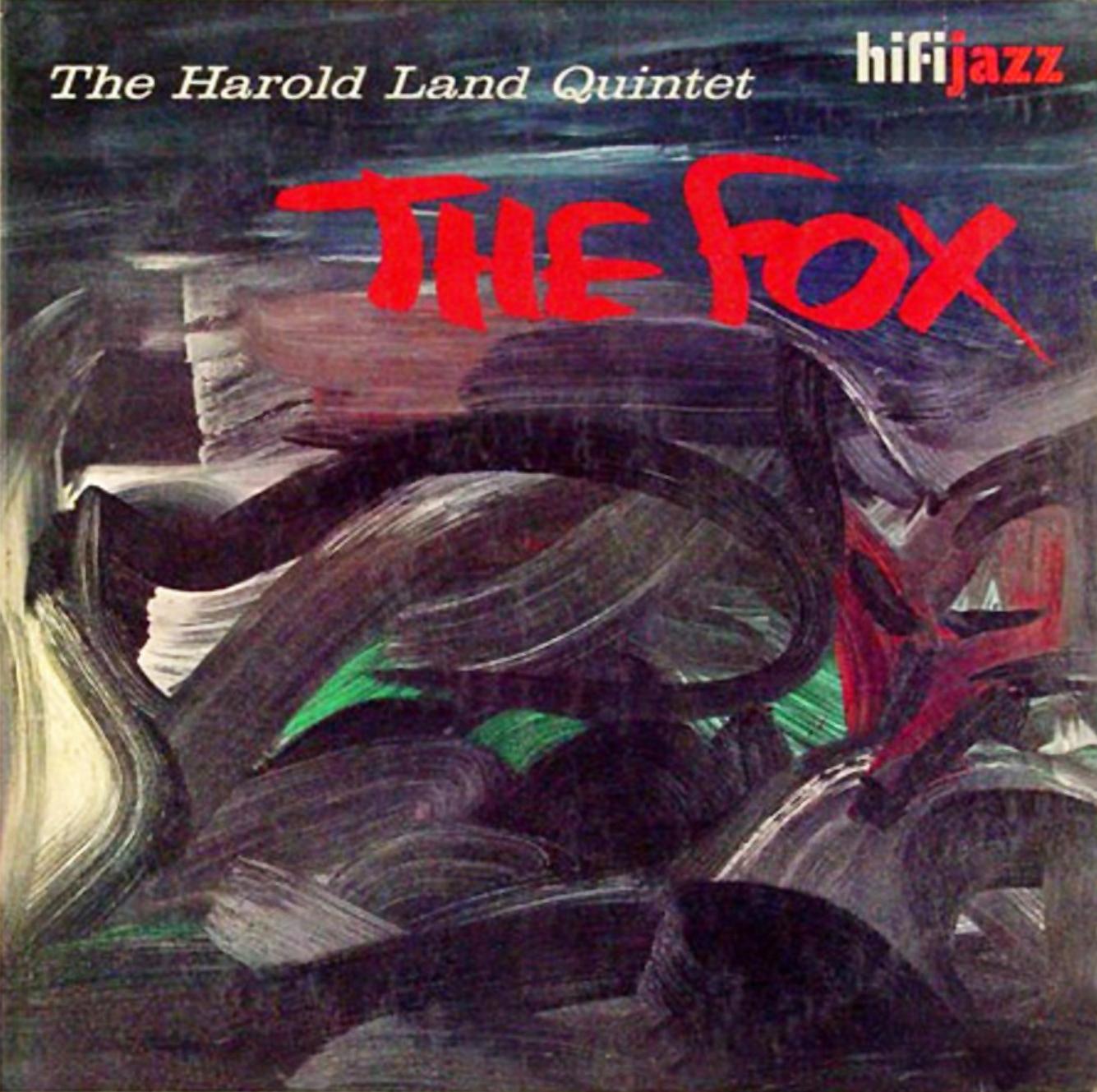

Edwards, the bop innovator, who has faultless timing, contagious pace and a relaxed fury that is apple pie for the ear, is a bluesman at heart. The blues oozes out of him during excellent renditions of his catchy, stop-time composition You Name It and the sumptuous, mid-tempo blues line of Hampton Hawes, The Sermon. That song conjures up the imagery of gin mills and moonshine passed on at Saturday night fish fries, miles and miles of cotton fields, the suffering and cathartic wailing of the black chain gang, and what surely was a reality to Edwards still in 1960, degrading redneck remarks that fill the heart with anger one does not really want to unleash except through blowing clean and hard.

His melancholic reading of What’s New suggests that Edwards knew by heart the lyrics to that song about a meeting of former lovers. Another Bull Durham vs e-cigs situation and a lesson for contemporary players: know your lyrics. And in the first place, get down those ‘standards’ anyway before exploring new vistas. Solid ground. So much for Prof. Durham’s class. Now get outta here and blow!