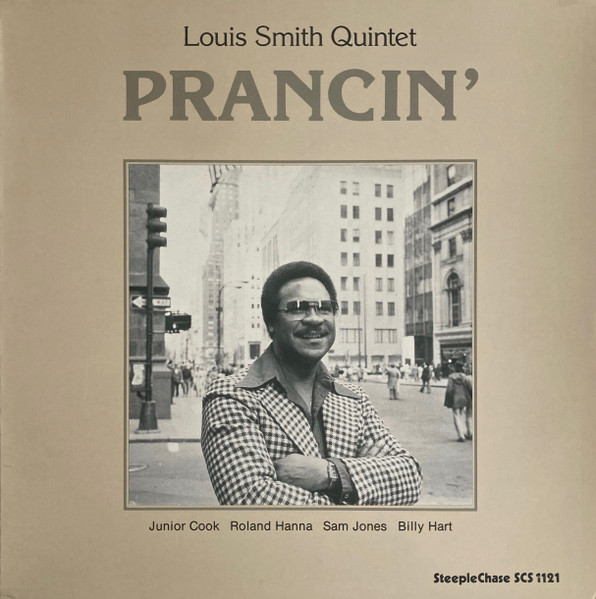

Mr. Smith goes to Copenhagen. As a matter of speaking.

Personnel

Louis Smith (trumpet, flugelhorn), Junior Cook (tenor saxophone), Roland Hanna (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Billy Hart (drums)

Recorded

on April 13, 1979 in New York

Released

as SCS 1121 in 1979

Track listing

Side A:

One For Nils

Chanson de Louise

Ryan’s Groove

Side B:

Prancin’

I Can’t Get Started

Fats

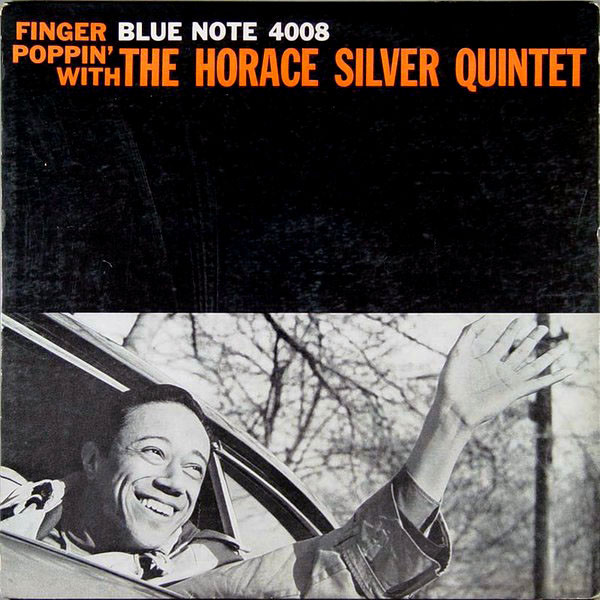

Memphis, Tennessee-born Smith was the nephew of Booker Little. Now there’s a hip trumpet blood lineage. While attending University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, young lion Smith shed wood with the likes of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and Sonny Stitt. Smith quit the scene after his Blue Note releases and focused on band directing at Booker T. Washington and University of Michigan and teaching at Ann Arbor public schools. After long radio silence, Smith reappeared on the Danish Steeplechase label of Nils Winther in the late 1970’s. Steeplechase was a safe haven for many stalwarts of mainstream jazz during the fusion and disco-infested years of torture. We’re talking Duke Jordan, Kenny Drew, Horace Parlan, Jimmy Knepper, Chet Baker, Walt Dickerson, Tete Montoliu, Hilton Ruiz and many more. It is still going strong as one of the to-go-to independent jazz labels. Quite a feat.

Smith recorded no less than twelve albums for Steeplechase from 1978 to 2004, though he remarkably succeeded to stay under the radar of the jazz universe until the end of his life in 2016. Dutch pianist and concert organizer Rein de Graaff, always on the hunt for unsung heroes, invited Smith to perform during De Graaff’s famed Stoomcursus Bebop lectures and concerts in The Netherlands. As he recounted recently, De Graaff also played with Smith in Detroit in the famed Baker’s Keyboard Lounge, “before an all-black audience.” De Graaff: “He was a very sweet man. The Steeplechase albums are good in general, but his Blue Note period is the real deal. Back then he was in his mid-twenties and on top of his game.”

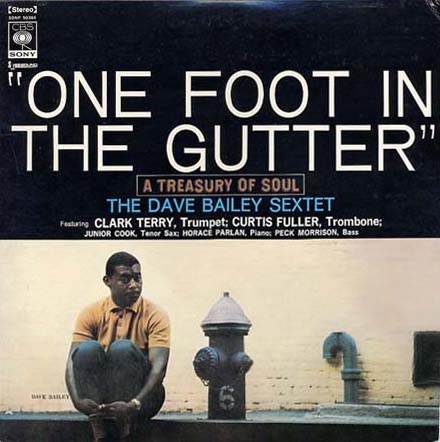

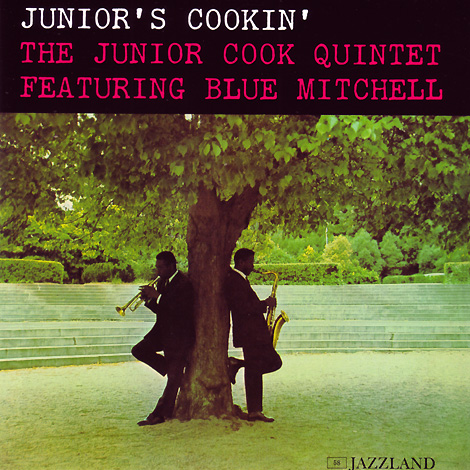

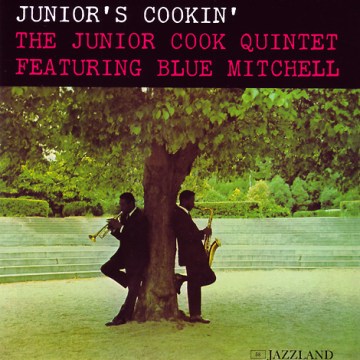

Louis Smith didn’t have to travel to Denmark to record for the Danish-based label. It was Greenwich Grooving Time in NYC and the trumpeter was in the good company of tenor saxophonist Junior Cook (a Steeplechase recording artist in his own right), pianist Roland Hanna, bassist Sam Jones and drummer Billy Hart. They play a solid set of hard bop, mid-and up-tempo swingers that feature the flexible style and bright sounds of Smith and the typically half-lazy phrasing of the great Junior Cook, who found a nice spot in the jazz realm between the legendary stylings of Hank Mobley and Dexter Gordon.

The thing that hooked me though is Smith’s balladry on flugelhorn. He added a ballad or two on every one of his twelve Steeplechase records. Smith’s lovely buttery soft lyricism is all over his Chanson de Louise. Furthermore, Smith builds a beautiful seven-minute solo during I Can’t Get Started, the Gershwin/Duke standard that suffers from silly lyrics (“I’ve flown around the world in a plane/I’ve settled revolutions in Spain/The North Pole I have charted/But I can’t get started with you…”) but boast a beautiful melody and attractive chord changes. It has always been a perennial favorite of jazz musicians and singers.

The importance of the American Songbook for jazz – and how well jazz musicians recreated Tin Pan Alley in their own image – cannot be overestimated. Smith runs away with I Can’t Get Started here, a man of sorrow and resilience and more than a couple of emotional nuances in between. A gem, no less. Pleasurable result of browsing through the Steeplechase catalogue of records by what back then were acclaimed or unsung middle-aged jazz men.

Listen on YouTube to Prancin’, Chanson de Louise and I Can’t Get Started.