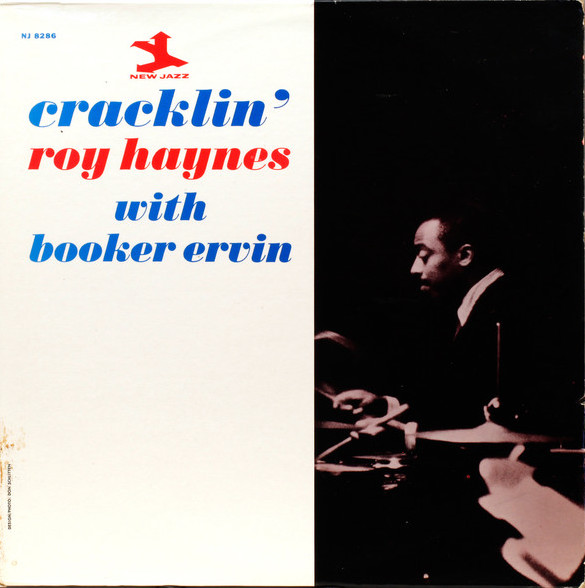

Cracklin’ is as good a title as any for an album by drummer Roy Haynes, also known as ‘Snap Crackle’.

Personnel

Roy Haynes (drums), Booker Ervin (tenor saxophone), Ronnie Matthews (piano), Larry Ridley (bass)

Recorded

on April 6, 1963 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as NJLP 8286 in 1963

Track listing

Side A:

Scoochie

Dorian

Sketch Of Melba

Side B:

Honeydew

Under Paris Skies

Bad News Blues

You can’t miss Snap Crackle. Let us pick a ‘few’ groundbreaking and/or iconic albums on which the currently 93-year old drummer appeared: Bud Powell’s

The Amazing Bud Powell, Sonny Rollins’s

The Sound Of Sonny, Thelonious Monk’s

Thelonious In Action and

Misterioso, Eric Dolphy’s

Outward Bound and

Out There, Oliver Nelson’s

Straight Ahead and

Blues And The Abstract Truth, Andrew Hill’s

Black Fire, John Coltrane’s

Impressions and

Newport ’63 and Jackie McLean’s

Destination Out. This series spans fifteen years (1949-63) of the seven decades in which Haynes has been active.

Haynes was part of Charlie Parker’s regular group from 1949 till 1952. A different time and place. Flyin’ with Bird, The One, in angst-ridden post-war USA, which saw The Russians marching. Uncle Sam, great Allied Force that had liberated Europe, had at the same time dropped The Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing thousands of innocent yellow-ish fellow human beings, and back home kept the black ‘citizen’ locked up in a cage. Astonishingly, lynchings were still not completely extinct below the Mason-Dixie line. Black men and women had to sit in the back of the bus. Job discrimination was commonplace, as were lower salaries. The elites feared a loss of the status quo and protected their privileges to the bitter end. Some said it was fear for and jealousy of abandon and sex that troubled them. That’s the old and worn paternalistic view that implies the only thing the black man and woman stand out with is swing. Instead, the elite felt discomfort with life as hollow men. The hollow man looks in the mirror and sees The Other, a free spirit! And suddenly is scared shitless.

Against the odds, Bird and his musical buddies, ibis birds, storm petrels and nightingales like Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, rare birds indeed, preached Beauty, Communion, Understanding, Empathy, through the unique art of spontaneous improvisation. They were musical masters with the kind of intuitive intellect that stuck a finger in the bloody wound of racism and said ‘Dear Lady, how do you do?’. Moreover, they were on a daring enterprise that the average American still knows nothing of. That’s probably because in the ensuing years, TV send him up to the couch, where he could watch Johnny Carson hide the miserable truths about life on the other side of the track. Was it any better in Europe? Yes, for a while Europe was keener in its appreciation of the (black) jazz message. And it takes better care of its professionals – white or black – that immerse themselves in the art of improvisation. But here too, few see the whole picture, here too Starbucks has won over more fans than Charlie Shavers. Rather silly. A flat cup of coffee may still give you a buzz. But jazz feeds the soul: it stimulates independence and interaction. One has to be his own man/woman and at the same time listen closely to the other. The most democratic of arts that crosses racial, age and gender boundaries and is not about division but inclusion and unity!

So Haynes flew business class with Bird and, stimulated by the innovations of Kenny Clarke, strayed away from the 4/4 beat on the hi-hat, going for a ‘ride’ cymbal accompaniment in sync with the Parker/Gillespie-intervals, with hectic life under the White Umbrella. (Parker, obviously, never hectic or nervous, instead revealing remarkable clarity and order at outrageous tempos) They acted upon their growing sense of melodic swing, Haynes creating many intriguing drum patterns particularly, a package that is or should be a benchmark for aspiring drummers to this day. As a logical consequence of his authority, Haynes recorded prolifically as a leader. His first album, Busman’s Holiday, was released in 1954 on Emarcy. His 1960 album on Impulse, Out Of The Afternoon, featuring Roland Kirk, Tommy Flanagan and Henry Grimes, is a perennial favorite of jazz fans around the globe. The sizzle and responsiveness of his playing on the 1968 Chick Corea classic, Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, is so beautiful it, well, is liable to bring tears. Late in life, Haynes made not one but two Grammy-winning albums: Fountain Of Youth (2004) and Whereas (2006).

Cracklin’ was released on New Jazz in 1963. It featured tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin, pianist Ronnie Matthews and bassist Larry Ridley. The date of the session is April 6, 1963. It is interesting to note that in that period, Haynes played with John Coltrane on the Newport Jazz Festival, on July 7 to be precise. While Cracklin’ smoothly stears along the coasts of hard bop, post bop and modal jazz, Haynes was cookin’ on another planet with Coltrane, replacing Elvin Jones, who was out for a snack on Alphabet Street. Both sessions rely on the Haynes specialty of snare rolls, Newport ’63 more heavily, spirited and sharp as a tack, an interesting change of vibe in contrast with the broader scope of Elvin Jones.

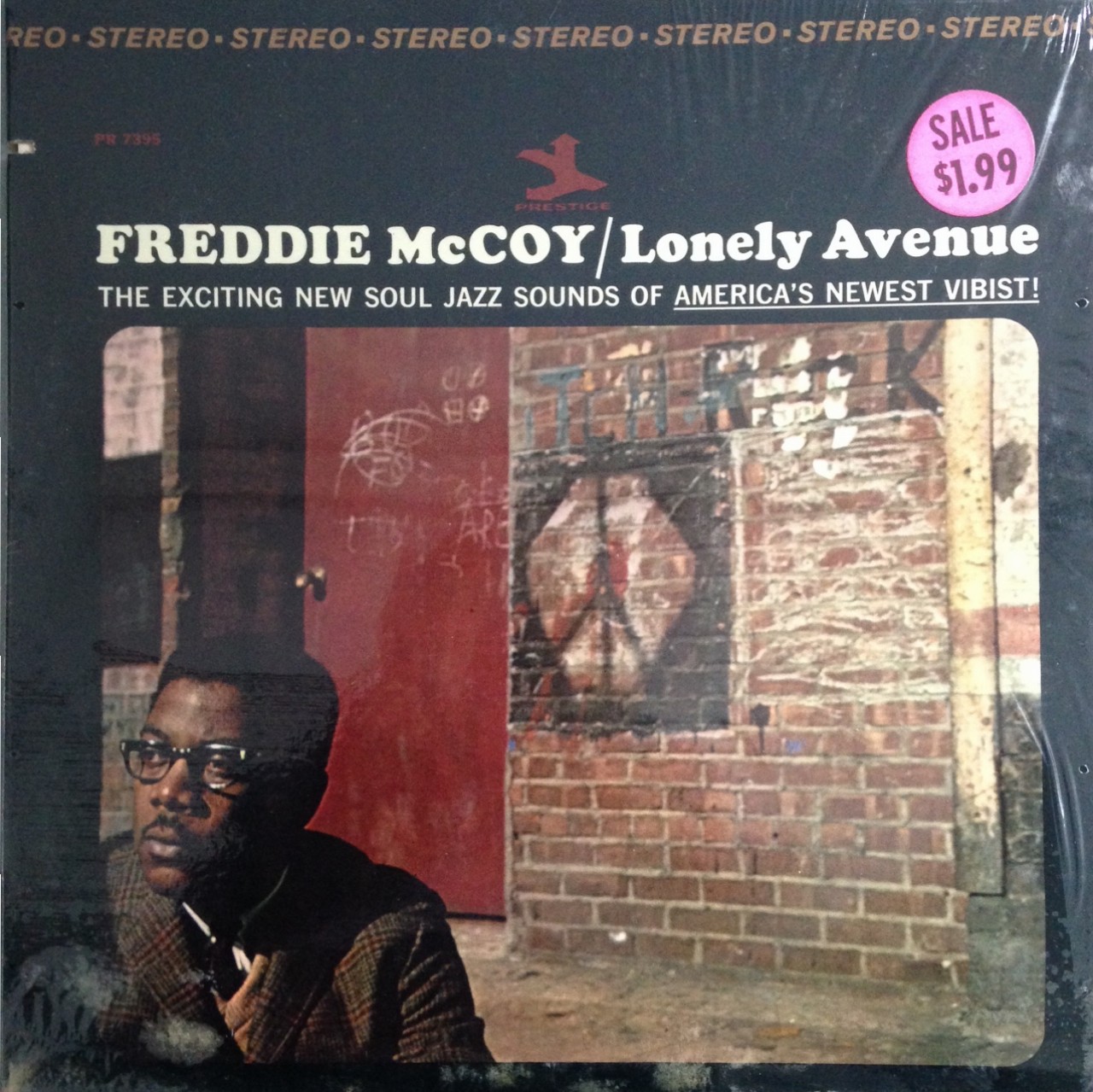

The Haynes snare is a superhero, Cracklin’ the blockbuster movie. In the winter, the drummer uses up the firecrackers of the stock that was left from New Year’s Eve and on summer camp Haynes is the leader that produces a light from stone and wood. From the word go, the light sets Scoochie in motion, a composition by Booker Ervin. Ervin thrives on the hard swing of Haynes. Haynes responds to the growing fire of “Book”, dancing through it like a dervish. Booker Ervin is a stimulating presence on any session, Cracklin’ is no exception. Generally, Ervin has been compared with John Coltrane. This doesn’t make much sense. There are shades of Coltrane in Ervin, but Ervin’s style, albeit thoroughly modern and obviously not without a certain amount of harmonic prowess, is less complex and has an emotional directness that reminds us of the Tough Tenors from Texas. Ervin was born in Denison, Texas in 1935. His indelible blues wail lands in your gut like a saucy and hefty kidney stew.

Then there’s pianist Ronnie Matthews, adding nimble lines that parade through downtown Dorian like supple jumping horses. Dorian is a tune by Matthews. It might refer to a lady, it might refer to a scale, either way it makes use of a ‘Trane-ish drone kept up vigorously by Haynes. Haynes also makes something special of the lovely melody by Hubert Gireaud, Under Paris Skies. His beat behind the piano solo of Matthews is ‘jungle’ at its most sizzling and groovy. His breaks on one of the album’s blues tunes, Ronnie Matthews’s Honeydew, are the drum equivalent of the soul shout ‘sock it to me!’

The message is loud and clear.