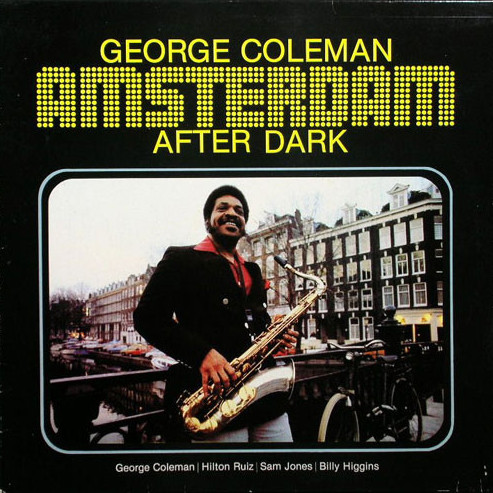

Leadership came late to George Coleman but he seized the opportunity with both hands.

Personnel

George Coleman (tenor saxophone), Hilton Ruiz (piano), Sam Jones (bas), Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded

on December 11 1978 at Sound Ideas Studio, New York City

Released

as SJP 129 in 1979

Track listing

Side A:

Amsterdam After Dark

New Arrival

Lo-Joe

Side B:

Autumn In New York

Apache Dance

Blondie’s Waltz

Amsterdam after dark, like many virus-ridden cities around the globe, has been looking pretty deserted these months. But it’s looking up these days as well, certainly by day, as life resumes a bit of its ‘normal’ course, at least for now, and people start roaming the streets again under the Spring sun. Well-deserved but our capital city looked stunningly beautiful without the crowd. One of the personal advantages in this general situation of misfortune has been that my fate – more precisely part of my work – has send me on the road, or better said,

on the canals, which unfolded themselves in front of me like a painting of Jacob van Campen or the meandering miracle lines of Parker’s

Ornitology. Even better still, Amsterdam seems to feel pretty swell. A short while ago it resembled a tiger in the zoo sauntering psychotically from one end to the other end of the cage, being gazed at enthusiastically by passersby but forgotten shortly after. Now it’s a sloth, idly hanging in a tree, scratching his armpits and taking a deep sigh of relief.

The beauty of nocturnal life in Holland’s capital city presumably was on the mind of tenor saxophonist George Coleman, who recorded his second LP as a leader, Amsterdam After Dark, in New York City – born New Amsterdam – but had been a respected guest of the Dutch scene in the late seventies. Like many of the great American modern jazz musicians such as Don Byas, Dexter Gordon, Johnny Griffin, Benny Bailey, you name ‘m, Coleman was enamored of The Netherlands, which at the time had a very extensive infrastructure of little towns and clubs and an appreciative jazz audience.

Amsterdam After Dark was recorded in 1978, your a-typical Flophouse review year, in fact a ‘first’ and most likely a ‘last’, but the exception had to be made for George Coleman, who should’ve recorded as a leader much earlier in his career, but rather inexplicably, considering his talent and reputation, enjoyed a belated debut release in 1977. The Timeless label from The Netherlands, responsible for Amsterdam After Dark, released ’77’s Meditation, a daring duet with the Spanish pianist Tete Montoliu, recorded while on tour in Europe.

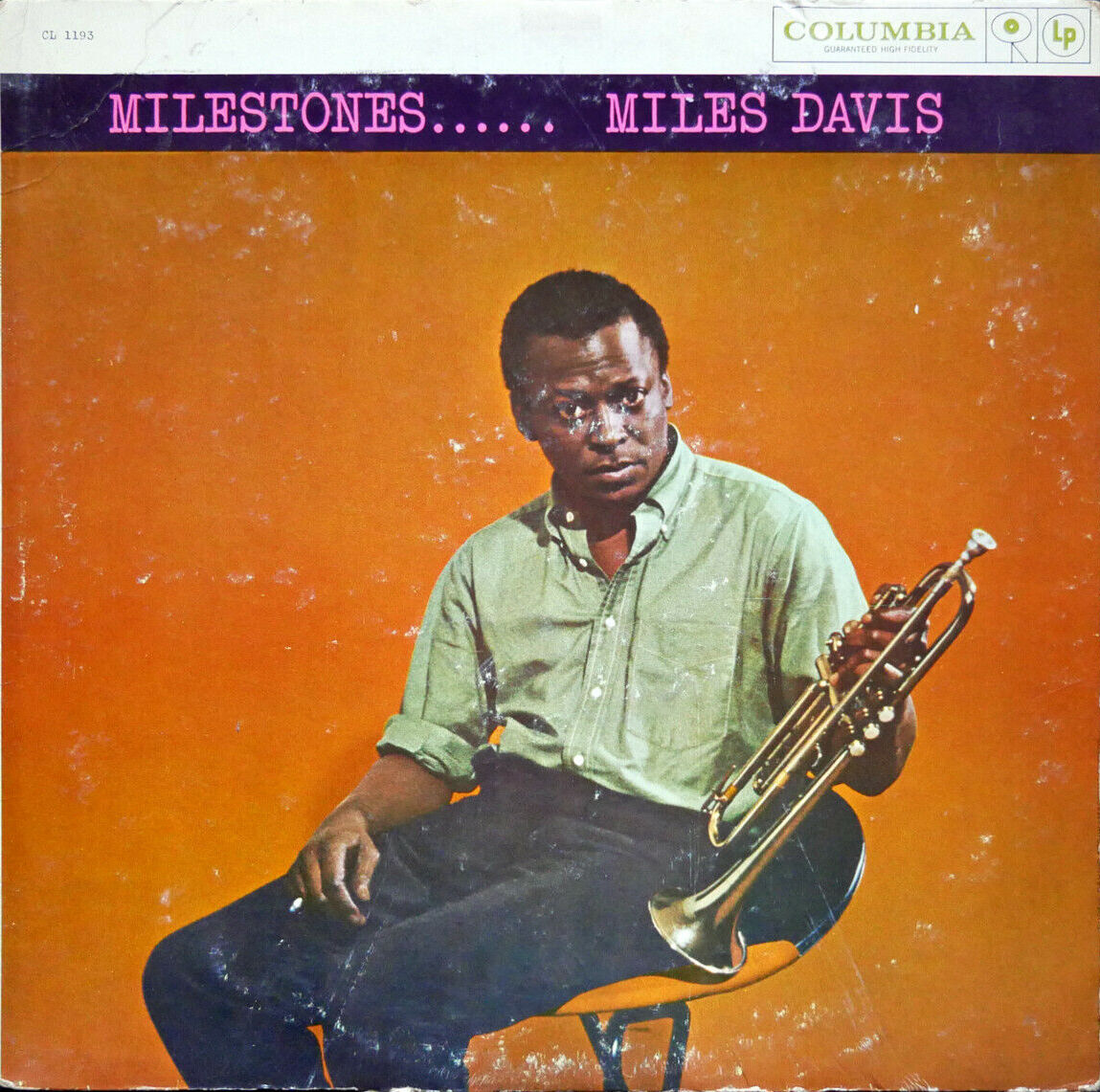

Obviously, Coleman is best known for his association with Miles Davis, who recruited the tenor saxophonist in 1963 as part of his stellar band of young lions – Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams. Coleman appeared on Seven Steps To Heaven and a series of stellar live albums, notably Four & More. Allegedly, Coleman was driven away by Tony Williams, who expressed the opinion that Coleman’s style lacked edge. I wonder then why did Williams agree with the inclusion of Coleman in the first place? By the way, Coleman later said that he wasn’t aware of Williams’ grudge and that it was the meager salary of the Miles Davis band that accounted for his notice. Fact is Coleman certainly was able to rip and roar around the Ring of Saturn but more than anything is a player of balance, substance and controlled fury and evidently couldn’t be bothered with the frenzied revolutionary musical spark of the late sixties, which probably accounts for his lack of exposure.

He’s one of those supreme musician’s musicians like Hank Mobley or Warne Marsh, which perhaps for the musicians concerned is more a curse than a blessing. He’s “Big G”, a passionate weight lifter, 85 years old and a staple of the New York City scene, a big influence on contemporary top guns like Eric Alexander and our own Ben van den Dungen. The Memphis-born saxophonist, childhood friend of the late Harold Mabern, Booker Little, Frank Strozier, Charles Lloyd and Hank Crawford, quite a bunch, recorded as recently as 2019, The Quartet, with Mabern, bassist Jon Webber and drummer Joe Farnsworth.

Coleman, who apprenticed with Ray Charles and B.B. King, came into prominence with Slide Hampton and Max Roach in the late 50’s. Apart from his work with Miles Davis, Coleman is admired for his contribution to Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage, which was recorded, by the way, with Miles Davis staples Ron Carter and, hmmm… Tony Williams. Coleman furthermore divided his time between cutting edge and roots music, appearing on records by organists Jimmy Smith, Reuben Wilson, Charles Earland, Don Patterson, Brother Jack McDuff, Shirley Scott and Brian Charette. That’s a lot of groove, buster.

There’s a good groove on Amsterdam After Dark, but it’s of a different nature. It’s layered. There’s the Latin-ish rhythm of the title track, a rhythm that goes back to the classic Blue Note sessions of the early 60s, in which the drummer on this record, Billy Higgins, was predominantly involved. Of course, the Latin influence has pervaded jazz from the start. Jelly Roll Morton stated that every jazz tune needed a Spanish tinge. There’s the Coltrane Quartet-drone of New Arrival, courtesy of Higgins and bassist Sam Jones. The melodies are fantastic and the organic mingling of melody and rhythm – breaks, stop-time, straight swing – of Coleman’s Apache Dance is particularly exciting. Pianist Hilton Ruiz, in top form, warms to the challenge.

Coleman’s Amsterdam After Dark tune is a crash course in storytelling but dangerous to try at home, a precisely articulated development from a gravely introduction, sly staccato stabs against the beat and whirling sentences that sustain momentum throughout, interspersed with pungent circular breathing. The introduction is notable. The sandpaper semi-tone, reflective of the intense and secretive whispers that lovers are prone to utter, makes you highly curious of things to come. Simple but effective and definitely a masterstroke.

Dutch young lion Gideon Tazelaar, 22-year old tenor saxophonist who resides in New York most of the time and is influenced by George Coleman, told me a little story recently during an interview for another publication that is so typical of the attitude and energy of the ‘old guard’. As it happens, Tazelaar was introduced to Coleman backstage at club Smoke and since then has followed weekly lessons at ‘Big G”s place, marathon sessions of playing, talking turkey and philosophizing. One day Tazelaar was gigging at a little place with his friend Felix Moseholm and the preceding afternoon had asked Coleman to join forces. Yeah why not. Coleman had to pass as a result of a pain in his back. However, when the lights had turned low downtown, the 85-year old saxophonist finally did turn up, cain in his right hand, case in his left hand. And, as per se, played as elegantly and balanced as ever. Taking care of business.

One of the big leaders in his own right.