BROTHERHOOD OF MAN –

Way back when, during that period when most jazz musicians eventually gravitated towards New York, musicians from the same origins usually had a special rapport. Everyone more or less felt comfortable in the presence of a fellow Native from Detroit, Chicago, Baltimore or St. Louis, sharing the same memories and peculiar cultural sensibilities of their hometown or place where they had grown up. One of the textbook examples of this sensibility is the Philadelphia connection of the Jazz Messengers line-up that Benny Golson arranged for Art Blakey, consisting of the Philly cats of Golson himself, Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons and Jimmy Merritt.

If citizenship is a bond, and to a lesser extent still is, imagine how close brothers and/or sisters that pursue careers always have been. In jazz, there are myriad examples of family ties, arguably more than in any other form of art. To a child, making music has always been more accessible than painting, sculpturing, cinema, photography. Households most of the time (and the church without exception) included a couple of instruments. And it was common practice for parents to direct their youngsters to the available bands – marching bands and the like.

Before the advent of the contraceptive pill, families were larger than today and thus held the promise of a bigger amount of interfamilial musicianship. Nonetheless the postmodern era spawned a number of sterling sibling configurations. Over the course of last week, a series of names popped into my head now and then, and some I found in books or liner notes I had coincidentally been reading. See below:

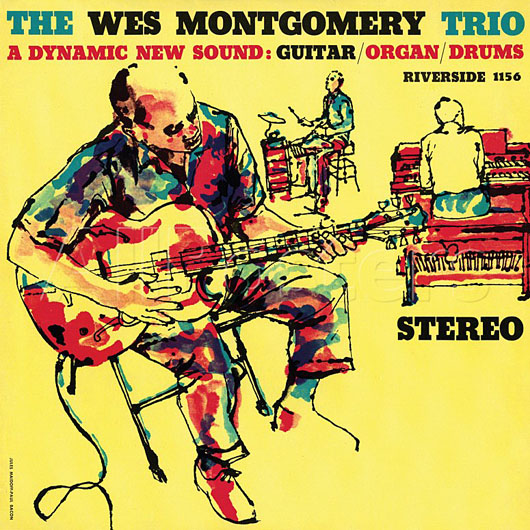

Hank, Thad and Elvin Jones. Wes, Monk and Buddy Montgomery. Conte and Pete Candoli. Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey. Cannonball and Nat Adderley. Bud and Richie Powell. Chuck and Gap Mangione. Lester and Lee Young. Jimmy, Percy and Albert Heath. Art and Addison Farmer. Johnny and Baby Dodds. Cecil and Ron Bridgewater. Michael and Randy Brecker. Kenny and Bill Barron. Ben and Gideon van Gelder. Wayne and Alan Shorter. Fletcher and Horace Henderson. George and Julia Lee. Kevin, Robin and Duane Eubanks. Roy and Joe Eldridge. Budd and Keg Johnson. I undoubtedly omitted a legion and I’m sad to say failed to bring in more than one woman into the equation. Help me out here.

To make matters more complicated and amusing, one need only point out the dynasty of father Ellis Marsalis and sons Wynton, Branford and Delfeayo. Indeed, the parent and sibling theme allows another round of pure jazz tidbit pleasure one may not perhaps view as pastime paradise but at any rate effectively kills time. There’s Albert and Gene Ammons. Jimmy and Doug Raney. You get the drift… Have fun!