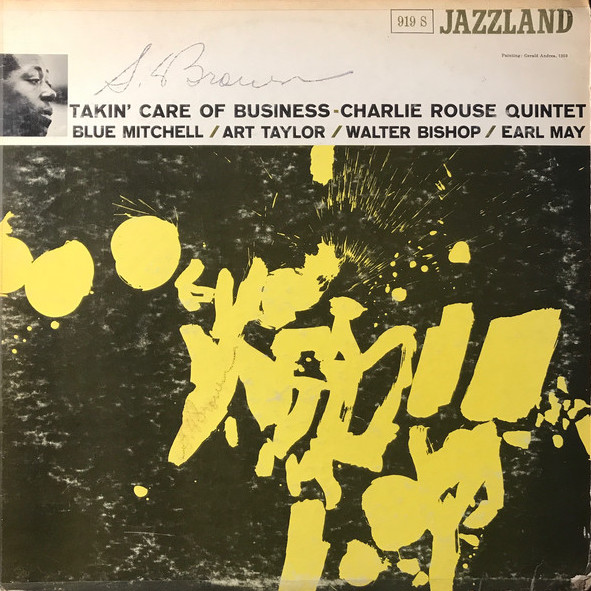

Monk’s long-running sideman takes care of business on his own.

Personnel

Charlie Rouse (tenor saxophone), Blue Mitchell (trumpet), Walter Bishop Jr. (piano), Earl May (bass), Art Taylor (drums)

Recorded

on May 11, 1959 at Plaza Sound Studios, New York City

Released

as JLP-19 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Blue Farouq

“204”

Upptankt

Side B:

Weirdo

Pretty Strange

They Didn’t Believe Me

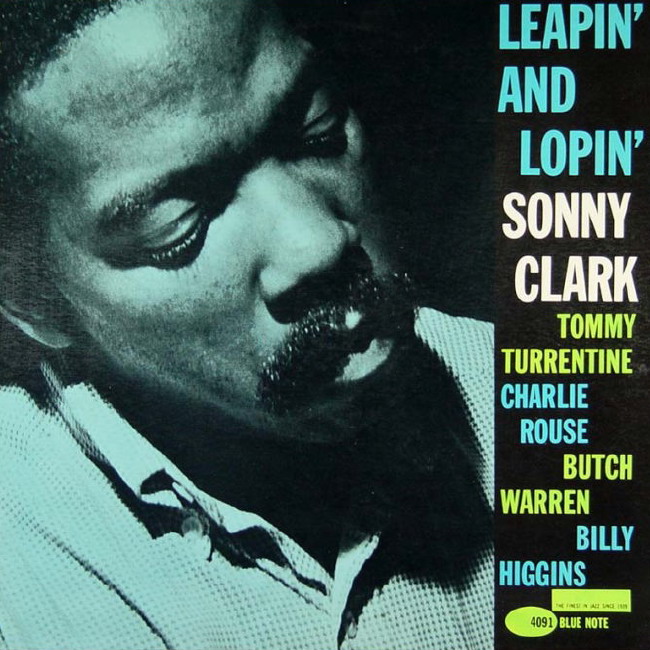

Aten-year stint in the group of Thelonious Monk ain’t chicken feed. This was the accomplishment of tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse and it speaks volumes about his skills, artistry and personality. Rouse was asked to join Monk at the start of 1959, the successor to the stint of Johnny Griffin and two short engagements of Sonny Rollins and former Monk associate John Coltrane. That’s a lot of tenor madness and a hell of a challenge. Nobody would’ve argued that Rouse is in the league of Coltrane and Rollins, nor would it have been easy to match the fire of The Little Giant. Indeed, for a lot of people, Charlie Rouse was a surprise pick, not least for a slew of young lions soliciting for the job, Wayne Shorter among them.

Rouse was already a veteran of sorts with a great track record, who had played in the bands of Billy Eckstine, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and Tadd Dameron and was a prolific sideman in the 50s. Preceding the Monk period, Rouse co-led the sophisticated group The Jazz Modes with French horn player Julius Watkins. After a nervous start, he got off well with The High Priest. It is said that Monk was particularly enamored by the genial, relaxed Rouse, which surely was, apart from his abilities, one of the reasons they gelled so well for such a long time. Rouse quickly adjusted to Monk’s focus on melodic improvisation.

Rouse’s contribution on Monk’s 5 By 5 record, sharing the frontline with Thad Jones, is especially spicy and belies the rigorous opinion that Rouse’s solo’s better be casually accepted, criticism ventured from his start with Monk and the kind that inclines to become myth and survive for numerous decades. It would be interesting as well to take a listen to Rouse the balladeer, predominantly his lush interpretation of When Sunny Gets Blue on We Paid Our Dues on Epic from 1961, a record that is equally divided between the groups of Rouse and Seldon Powell.

Takin’ Care Of Business may not be the most inspired of titles. Who didn’t take care of it? However, it’s a strong effort from a top-notch group that further includes trumpeter Blue Mitchell, pianist Walter Bishop Jr., bassist Earl May and drummer Art Taylor. Mitchell contributed Blue Farouq, a hip blues line that also is featured on organist Melvin Rhyne’s Organ-izing and Junior Cook’s Junior’s Cookin’. Interestingly, “204” in fact is Randy Weston’s wonderful waltz Hi-Fly, the initial version with a slightly differing melody. Rouse’s Upptankt (meaning what?) and Kenny Drew’s Weirdo provide the saucy bop contrast to the jaunty take on Jerome Kern composition They Didn’t Believe Me and Randy Weston ballad Pretty Strange – which indeed is pretty strange, certainly not your usual melody with a sequence that is somehow unresolved, moving in front of the bedroom window like a thin fog and rather intriguing in its own weird way.

Solid mainstream from a punchy band, Rouse flowing and with sustained, logical ideas and slightly edgy tones opposite Blue Mitchell’s sinuous, exuberant lines and Walter Bishop Jr.’s charged bop style. Turn-of-that-decade quintet stuff that merits plenty of attention.