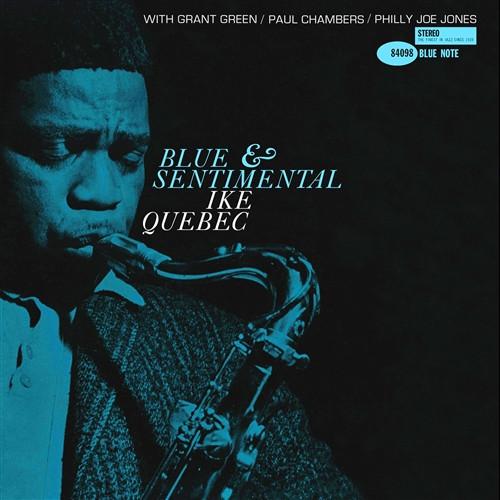

Ike Quebec’s resonant, breathy tone, deep as if coming from a velvet cave, is plainly irresistable. It’s in full bloom on Blue & Sentimental, one of Quebec’s 1961 comeback albums on Blue Note, a set of moving ballads and gutsy blues performances.

Personnel

Ike Quebec (tenor saxophone, piano A2, A4), Grant Green (guitar), Sonny Clark (piano B3), Paul Chambers (bass), Sam Jones (bass B3) Philly Joe Jones (drums), Louis Hayes (drums B3)

Recorded

on December 16 & 23, 1961 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 4098 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Blue And Sentimental

Minor Impulse

Don’t Take Your Love From Me

Blues For Charlie

Like

Count Every Star

Quebec was a veteran of the swing era who recorded with Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins, Hot Lips Page, Trummy Young, Ella Fitzgerald and Cab Calloway. In the late forties, Quebec recorded for Blue Note while also serving as an arranger and talent scout, stimulating the careers of Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell in the process. Both the decline of big bands and the struggle with a drug addiction kept Quebec under the radar in the fifties. At the end of the decade, Alfred Lion issued a series of Ike Quebec singles for the jukebox market, checking out if Quebec would gain audience attention after years of low visibility. The singles were well-received. Subsequently, the albums that Blue Note released in 1961 and ‘62, Heavy Soul, It Might As Well Be Spring, (with organist Freddie Roach) Blue & Sentimental and Bossa Nova Soul Samba (the latter with Kenny Burrell) were good sellers. Easy Living was released posthumously in 1987. Quebec’s comeback was cut short by lung cancer. He passed away in 1963.

Ike Quebec’s style is accesible but not plain, his sound imposing but not theatrical. A lusty mix of elegant phrasing and a tone with a slight vibrato that switches suavely from breathy whispers to solid honks. Ben Webster-ish, containing that same blend of tenderness and hot swing, with a whiff of romance borrowed from Coleman Hawkins. Do you ever put on Blue & Sentimental on a bright sunny morning? Of course not. It’s a full-blooded after-midnight album. Can’t you see yourself sunk into a battered old chesterfield chair with a 10 year-old single malt and Hajenius cigar in hand? Smoke billows upwards to the ceiling. Ponderings of the incompatible natures of Venus and Mars billow upwards to the ceiling as well, as Quebec delivers an achingly romantic version of Don’t Take Your Love From Me. The demons of a grinding working day and a general mood of nausea are driven out by the lithe, jumpin’ blues of Minor Impulse. Can’t you see? Well, I can. Battered Old Chesterfield is my middle name.

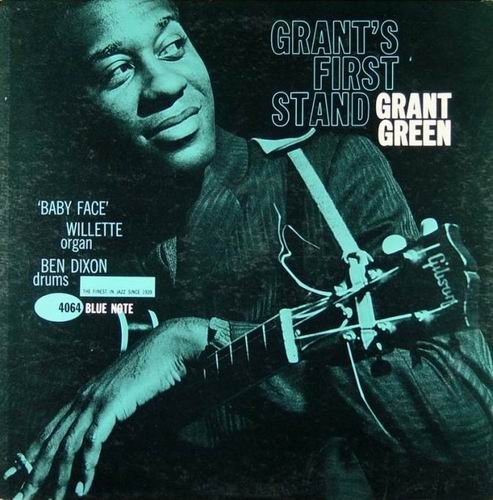

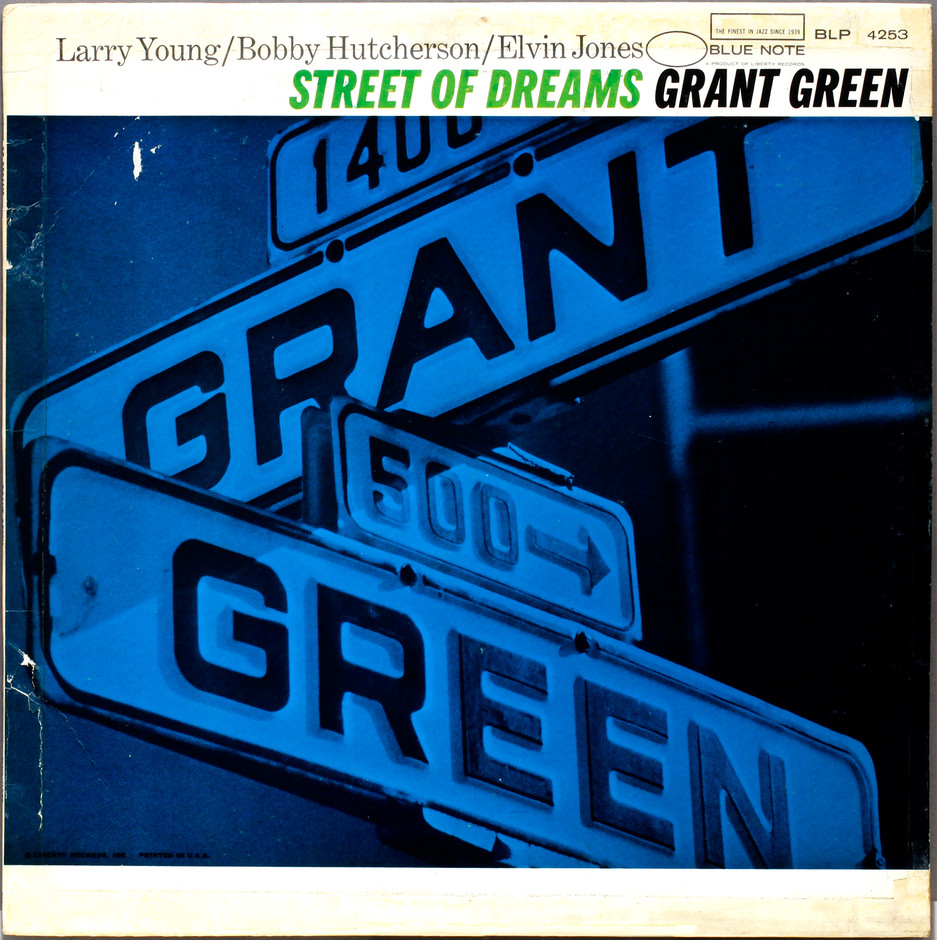

As far as ballads go, they rarely come as smoky as Blue & Sentimental. Quebec’s husky tenor carries the tune, with just the right punch to add steam. Guitarist Grant Green, finishing his first – prolific – year at Blue Note headquarters, is a perfect companion to Quebec’s warm-blooded blowing. Just slightly dragging the beat with his fat-toned, sustained Gibson licks and spicy excursions into bluesland, Green’s balladry is delightful. On the faster tunes, Green’s propulsive lines sparkle. Chambers and Philly Joe Jones also comprise an outstanding match with the veteran tenorist. No need to introduce Mr. PC. From his magnificent, allround package, Chambers chooses tasteful, chubby, blues-drenched notes for the ballads and fat-bottomed, lively walkin’ bass lines for the uptempo tunes. Philly Joe Jones provides sensitive and sprightly support, presenting a bonafide Papa Jo Jones beat in Quebec’s original tune, the lurid cooker Like.

The album ends with Count Every Star, a take from the December 23 session including Green, Sonny Clark, Sam Jones and Louis Hayes. Excellent stuff, but one wonders why Alfred Lion thought the inclusion necessary. The CD re-issue (also available on Spotify) reveals a spirited uptempo take of Cole Porter’s That Old Black Magic. Another sparse, piano-less gem that shows the fine rapport between the underrated master of the tenor saxophone and his illustrious supporting crew.