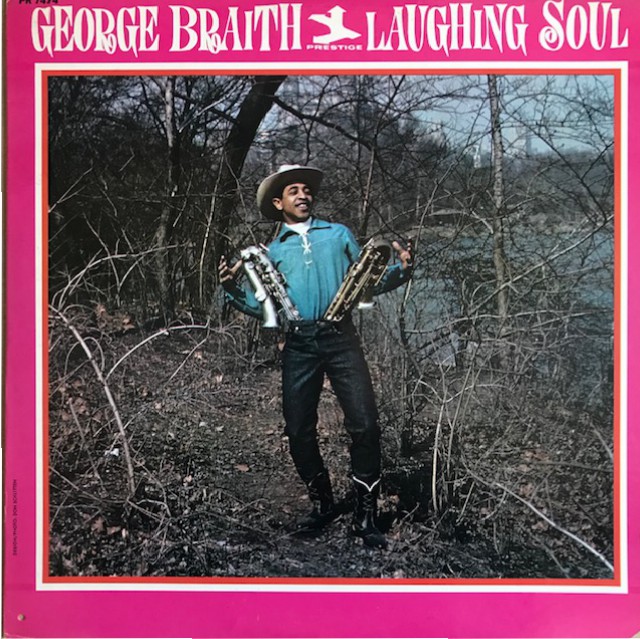

From Blue Note to Prestige: the short career of the enigmatic George Braith.

Personnel

George Braith (alto & soprano saxophone), Big John Patton (organ), Grant Green (guitar), Eddie Diehl (rhythm guitar), Victor Sproles (bass), Ben Dixon (drums), Richard Landrum (congas)

Recorded

on March 1, 1966 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PRLP 7474 in 1966

Track listing

Side A:

Hot Sauce

Chop Sticks

Chunky Cheeks

Crenshaw West

Please Let Me Do It

Side B:

Coolodge

With Malice Toward None

Little Flame

Cantelope Woman

In case you may need the accompanying soundtrack to your longing for Spring, dearie blossoms, bouncy squirrels, happy faces in the crowd instead of cold, gusty winds and dark and dreary skies, go to George Braith’s Laughing Soul. Coming season’s perfect pick. It’s juicy, uplifting and applies a variety of contagious rhythms that transforms the most wanted stuffed shirt into Jennifer Lopez’s lean and lanky nephew.

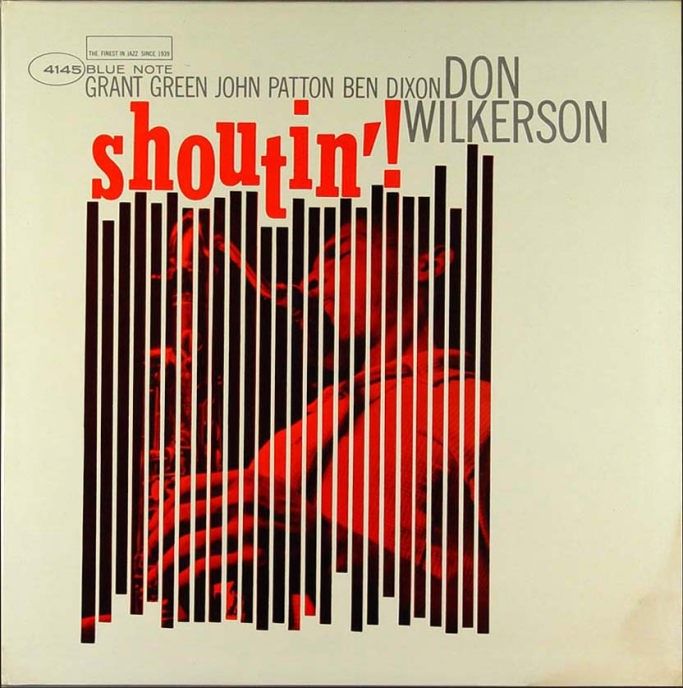

Long life, short recording career. Braith, 83 years old, born in New York City from West-Indian parents, was a sight to see and hear from the start, playing two horns at once just like Roland Kirk. Inventor of instruments like the Braithophone, which was constructed from a straight alto and soprano saxophone, Braith was featured on organist John Patton’s Blue John in 1963 on Blue Note and subsequently recorded two albums as a leader for label boss Alfred Lion: Soul Stream and Extension, featuring ace guitarist Grant Green.

Braith switched to Prestige in 1966. (The only other short burst of recording activity was in 2006/2007, when Braith released two albums on Excellence) Precursing the progressive oddity Musart, it’s Laughing Soul that hits bull’s eye, presenting concise, to-the-point and catchy tunes with the help of a rhythm section that defined soul jazz in the early/mid 1960’s: Grant Green, organist John Patton and drummer Ben Dixon. The band is completed by bassist Victor Sproles Jr., the rhythm guitar of Eddie Diehl and conga of Richard Landrum. The liner notes by the uncompromising Christopher Peters refer to Braith’s stint with Blue Note: “… a few record dates on which his ability to play two or three horns simultaneously became more important then what he played or what he expressed. Something or someone put the perspective out of whack; the means became the end.” Christopher evidently felt no need to branch out and look for another job.

Seriously, all tunes are killer, no filler. Vibrant and upbeat, six compositions are by Braith, two by Dixon, one by Tom McIntosh, the beautiful moody ballad With Malice Toward None. Carribean rhythm is omnipresent, notably pervading the Dixon classic Cantalope Woman, a woman whose main interest probably was the act of strollin’ on a tropical island. Typically unpretentious but nifty, unusual bar length is one of many charms of Dixon’s Latin blues. Braith’s r&b-drenched Please Let Me Do It is a sassy melody that features biting licks by Grant Green. This Gibson’s on fire.

Braith’s tight-knit band sounds joyful and inspired. It hardly matters that the leader isn’t a very strong soloist. There’s Green and Patton for compensation. Furthermore, Patton is uncommonly versatile as accompanist, adding spot-on touches to the repertoire with a variety of sounds like the flute-tone of Cantelope Woman and the churchy organ of Coolodge, an intriguing tune that seals a surprising bond between classical, vertical lines and groove and grease.

From the opening potential jukebox favorite Hot Sauce, hot little numbers as Chop Sticks and Chunky Cheeks (the art of song titles shouldn’t be underestimated) to chitlin’ circuit contender Cantelope Woman, Laughing Soul is a merry affair, bubbling with life, and definitely George Braith’s finest effort.

Laughing Soul is on out-of-print vinyl and released on CD in Japan. Only three tunes are on YouTube. Here’s Crenshaw West.