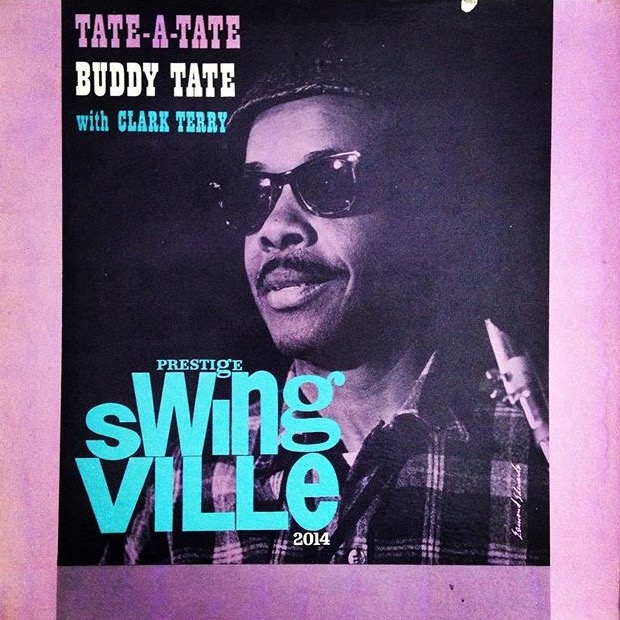

Nobuddy, well at least few from the swing era, nurtured such a long career as tenor saxophonist Buddy Tate. Tate-A-Tate, smokin’ cooperation with young lions and Clark Terry, is one of his finest efforts.

Personnel

Buddy Tate (tenor saxophone), Clark Terry (trumpet, flugelhorn A1), Tommy Flanagan (piano), Larry Gales (bass), Art Taylor (drums)

Recorded

on October 18, 1960 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as SVLP 2014 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Groundhog

Tate-A-Tate

Snatchin’ It Back

Side B

All Too Soon

Take The A-Train

#20 Ladbroke Square

Listening to Buddy Tate feels like watching a movie starring John Wayne. Wayne’s gruff, spitting, punch-you-in-the-gut cowboy characters hold no bars, they are a hybrid of horse sense gumption and primitive emotions shimmering under the surface, likely to explode any minute. His presence on the screen is lethal. Yet there’s something of the likeable teddy bear uncle in him as well. One of Wayne’s finest movies is True Grit and true grit – Wayne’s left lung was removed in 1964 but he managed to complete more than 175 movies in a career that spanned more than 50 years before succumbing to cancer in 1979 – was his middle name.

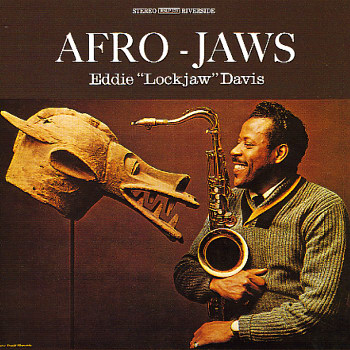

It is terminology well suited for Buddy Tate, perhaps not such a heavy smoker in a literal sense, but definitely figuratively speaking. And like Wayne, Tate enjoyed a long career. During his life most of the major innovations in jazz history had been developed. Born in Sherman, Texas, Tate played in the territory bands in the Southwest in the late 20s. He was the tenor saxophonist in the Count Basie band from 1939 to 1948, an impressive ten-year stint in the hardest swinging big band in the world, which partly coincided with the tenure of Lester Young. Tate was hired by Basie after the sudden death of Hershel Evans, one of Tate’s major influences alongside the father of jazz tenor, Coleman Hawkins. The following decades, Tate recorded prolifically with, among others, Buck Clayton and Illinois Jacquet. And who doesn’t fondly remember the exciting Very Saxy album with Coleman Hawkins, Arnett Cobb and Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis? Tate passed away in 2001.

Tate is a real blues man and a “tough tenor” as they say, an accessible player that blows honest stuff that comes deep from the gut, marked by smears and elongated mischievous utterings. The kind of player that devours a riff. He stands for entertaining stories and an architecture that is made up of sure-shot entrances, well-structured middle parts and sustained excitement to the end. In a sense, swing-based musicians like Tate are precursors to the soul jazz practitioners, playing music of the people for the people.

So by 1960, the year of his Tate-A-Tate record, Tate was already a veteran. Tate was part of a select club of swing players whose shop rarely closed down, not even during summer holidays. He had already enjoyed a 10-year residency at the Celebrity Club in Harlem, NYC and would continue to perform there until 1974. He also made a couple of solid records with a mixture of old pals and the new breed on Prestige, instigated cleverly by label boss Bob Weinstock and A&R man Esmond Edwards, who realized that jazz styles are by no means totally opposite entities but just different enough to put an edge to the results. The top-notch Tate’s Date with bop pianist Sadik Hakim preceded Tate-A-Tate, which featured trumpeter Clark Terry, his former colleague from the Basie band – Terry went with Ellington in the mid-40s – and the modernists Tommy Flanagan, Larry Gales and Art Taylor.

Tate-A-Tate – pun intended, don’t you love that good-old jazz word play? – is the kind of simultaneously relaxed and driving record that makes you all warm inside, as if cubicles of roasted marshmallows have just taken a rest at the bottom of your belly. It’s dedicated to fast, medium and slow-tempo blues. Tate and Terry do thorough workouts on two pieces from the Ellington book – swinging madly and gaily on (Billy Strayhorn’s) Take The A-Train. Tate reminds us of his delicious balladry on All Too Soon, all glowing coal on the BBQ and aromatic whiskey flavor.

It’s the little details of this spontaneous recording that reveal the greatness of old-school masters like Buddy Tate and Clark Terry. Tate’s sensuous vibrato and thunderous low-register honk put the dot on his perfectly developed sentences of the slow-medium blues tune #20 Ladbroke Square – a Tate composition. Terry’s wondrous out-of-time entrance of the frivolous blues line, Snatchin’ It Back, kick starts the kind of dynamic, ebullient solo the trumpeter had a patent on during his long and brilliant career – unbelievably, Terry played both trumpet and flugelhorn during the course of A-Train and the slow blues Groundhog, one in the left hand, other in the right hand. No use being a master if you don’t once in a while deliver the goods grandiosely, right.

Terry’s Tate-A-Tate builds on the pun of the title, a “jumpin’ blues” with solid breaks and lovely, interweaving tenor sax and trumpet lines. It’s a high-level conversation of smoky Tate and extravert Terry, underscored by rollicking rolls from Art Taylor, omnipresent drummer in the jazz scene of the late 50s and early 60s. The balanced but booming responses of Tate and Terry not only to pianist Tommy Flanagan’s elegant stories and sensible accompaniment but also to Taylor’s cracks from the hip constitute some of the biggest enjoyments of the thoroughly entertaining and sophisticated Tate-A-Tate session.

Listen below. Spotify wrongly credited the record to Tate & Claude Hopkins. Tate-A-Tate starts at number 8.