Photography: Ronaldus

Charming, talkative Peter Guidi guides us through his adventuresome career as flutist, saxophonist, bandleader and educator. “I teach my students the rudiments, thereafter it’s up to them. It’s essential to follow your heart and play what you believe in. Because the audience can hear that.”

Teach your children well, sang Stephen Stills. That’s exactly what Peter Guidi has been doing for thirty years now. Well,

more than well. The Scottish-Italian, Amsterdam-based Guidi, like one of his all-time heroes Cannonball Adderley, a likable, outgoing gentleman, displays boundless, devoted enthusiasm for nurturing young jazz talent. Don’t come around suggesting to Guidi the popular view that jazz is dead or bereft of a promising future. His slightly curled hair shakes back and forth, his eyes widen: “Are you kidding?! Not when you’re hearing all those youngsters in my orchestras. They play with their heart and soul. With joy and guts. Even with a not yet fully-developed technique they regularly catch me by surprise. Their purity is heart-warming. I send them on stage as early as possible, let them make a lot of flying hours. You can’t learn jazz from a book. You know what Einstein said, and he’s a pretty smart fellow:

‘The only true knowledge is experience, everything else is merely information’. Who’s gonna argue with that? Not only do I feel that jazz is alive, there is the bigger picture. Some of those boys and girls have become friends for life because they share a passion.”

“Jazz provides a great lesson in life. Especially during these times of ‘me, me, me…’ I-this, I-that, the faces in front of the computer screens… Without communication and interaction with other people, life isn’t worth much. Practicing technique to become the fastest gun in the West, alone in your room, makes no sense. Playing together does. Playing jazz involves mutual respect, listening skills, sharing. Furthermore, and this makes it so beautiful, it involves the growth of a personal voice. You have to tell your own story. But, again, within the framework of the group.“

“I’ve had parents come up to me and tell me that their son or daughter, whether he or she has pursued a career in music or not, has grown as a human being. They learn to work as a team and improvise. And life is all about improvisation. We don’t know what the heck is going to happen tomorrow! Some time ago, I encountered a lady who had been in my Jazz Juniors band. She has a very hectic, important job and told me that she always thinks about my lessons in stressful situations, that her motto had become: use your imagination, improvise! You know how good it felt to hear that? Wow!”

Guidi’s accomplishments in the Dutch jazz educational landscape are unmatched. He’s sort of a Dutch equivalent of educational legends in the classic age of jazz, like Captain Walter Dyett from DuSable High School in Chicago, who showed the way to Nat King Cole, Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin, Clifford Jordan, Richard Davis and many others. Guidi built up the Jazz Department of the Muziekschool Amsterdam from scratch in the mid eighties, running numerous prize-winning youth orchestras in the process and kickstarted the careers of countless major talents such as Joris Roelofs, Lars Dietrich, Ben van Gelder, Gidon Nunez Vas, Gideon Tazelaar and Daniel Keller. Guidi has always taught using an unbeatable method he calls ‘the three F’s’: Firm, Fair and Funny. Strict but sincere, with some humor thrown in to illustrate important points. “And never bullshit. Kids can smell bullshit a mile away! If you find yourself at a loss in an educational situation, just say so. Say, ‘well, I don’t really know, but I’ll get back to you with an answer next week.’ They accept that and like you for it because it is honest.”

An optimist at heart, Guidi nevertheless expresses worry about the prospects of contemporary students. “Long term engagements have become practically out of the question. Most young players play one-offs. And later when they’re not young talents anymore, a different reality sets in. The club wants you, but your next performance will be two years later! It’s heartbreaking because the amount of talent today is amazing. What’s my advice to young players? Follow your heart, follow your dreams, always. But at the same time, keep one foot on the ground. In the conservatory, everybody digs Coltrane and Chris Potter but outside few people even know who Louis Armstrong is, let alone Charlie Parker or Lee Morgan. So? The world is your oyster, you have many choices and opportunities. You can of course diversify and do commercial stuff to help you financially, but if you want to dedicate your time exclusively to jazz, then try to get a teaching job or go study something else as well. All of these young jazz students have the talent, dedication and creativity to become anything he or she wants to be. If they studied the equivalent amount of time with the same amount of effort and discipline they could become brain surgeons. That shows you how hard they work. But at the end of it medical students have a career ahead of them whereas jazz students don’t know where the next gig is coming from.”

“What kind of jazz do I teach? Mostly hard bop! It has groove, blues, great chord sequences, instantly recognizable melodies, energy and integrity. My youngest students are nine, ten years old. They’re little jazz barometers, so to speak. I’ve been doing this a long time, I have a pretty good idea of their mindset. Often without any interference on my part, these kids request to play pieces like Work Song, Moanin’, Sister Sadie, Blues March, The Sidewinder, Song For My Father, Sugar! Tunes that are not too complex where you can improvise using pentatonics or a blues scale. Chronologically, bebop comes first of course, but in educational terms, it’s better to start with hard bop. And earlier some catchy blues like C-Jam Blues. It gives them security and convinces them to jump off the diving board. Not to be afraid of ‘wrong’ notes. Duke Ellington said: ‘There’s no such thing as a wrong note. If you play it long enough, it turns into a right note.’ The blues reflects that wise statement. ‘Wrong’ blue notes are ingrained. They are what make it sound blue.”

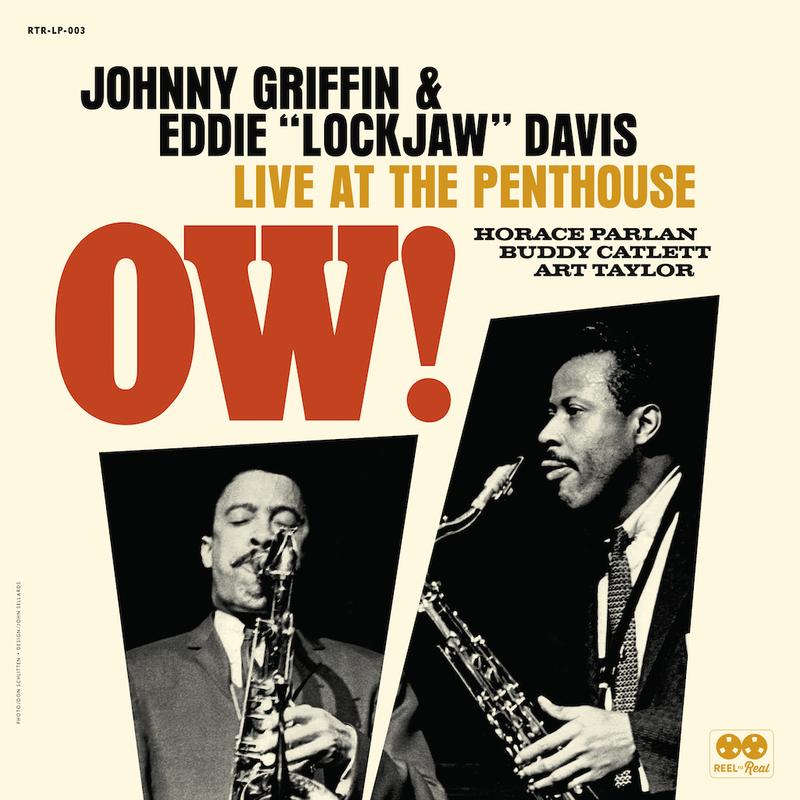

Before Guidi found his educational destiny in the capital of The Netherlands, the young man’s unorthodox path led him from Glasgow, to Jersey to Milan. As a kid in Glasgow he listened to Sinatra and opera in the Scottish-Italian household and was held spellbound by the slow-dragging bass voice of the legendary Voice Of America Jazz Hour radio presenter Willis Coniver. Soon playing clarinet for his beloved mother and whistling bebop tunes almost 24/7, on Jersey Guidi set his mind on obtaining a saxophone from the only music store on the island and, once he purchased it with the money earned working in his father’s restaurant, had the opportunity via the Jersey Jazz Club to jam with the likes of Johnny Griffin, Art Taylor, Ronnie Scott and flutist Harold McNair. At the age of eighteen he was the chauffeur of Ronnie Scott, who wanted to drive to the sole booking office on the island to bet on the horses as soon as he got off the airplane. A professional in Milan and London, the hard road of making a jazz living became apparent, the pleasures of living and breathing with legends like Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis, Sonny Stitt and Dexter Gordon as well. And then, Amsterdam. The liberal city which he loves like no other town in the world and has been calling his home for over three decades. “Opportunity knocked. I was asked for a teaching job in the Muziekschool Amsterdam. I had a lot of experience as a musician playing at major festivals and also in small jazz clubs some no more than holes in the ground. That experience allowed me to pass on some practical knowledge. I learned a lot too because you can’t really learn how to teach except by doing it.”

Perhaps the DIY attitude necessary to find your way on an outpost like Jersey during the winter season accounts for Guidi’s level-headed, entrepreneurial spirit. “Yes. And also the typical immigrant attitude of my family. Be your own boss, like my father said. Well, I became my own boss once I moved to Milan. I played in soul bands. I still love soul music. I did South-American stuff with real Argentine and Brazilian bands playing extended stints in top Saint Moritz hotels. The only down side with the Argentine band was wearing a poncho, spurs, one of those belts with coins on it. That might look cool when you play guitar, but sax? I looked and felt like a complete idiot! But with those earnings I bought a soprano saxophone. There was no Real Book or Aebersold method back then you understand! No Jazz Conservatory. You had to learn by playing on stage. If you wanted to learn Cherokee, you had to ask somebody to write down the chord changes for you. And trust your ears.”

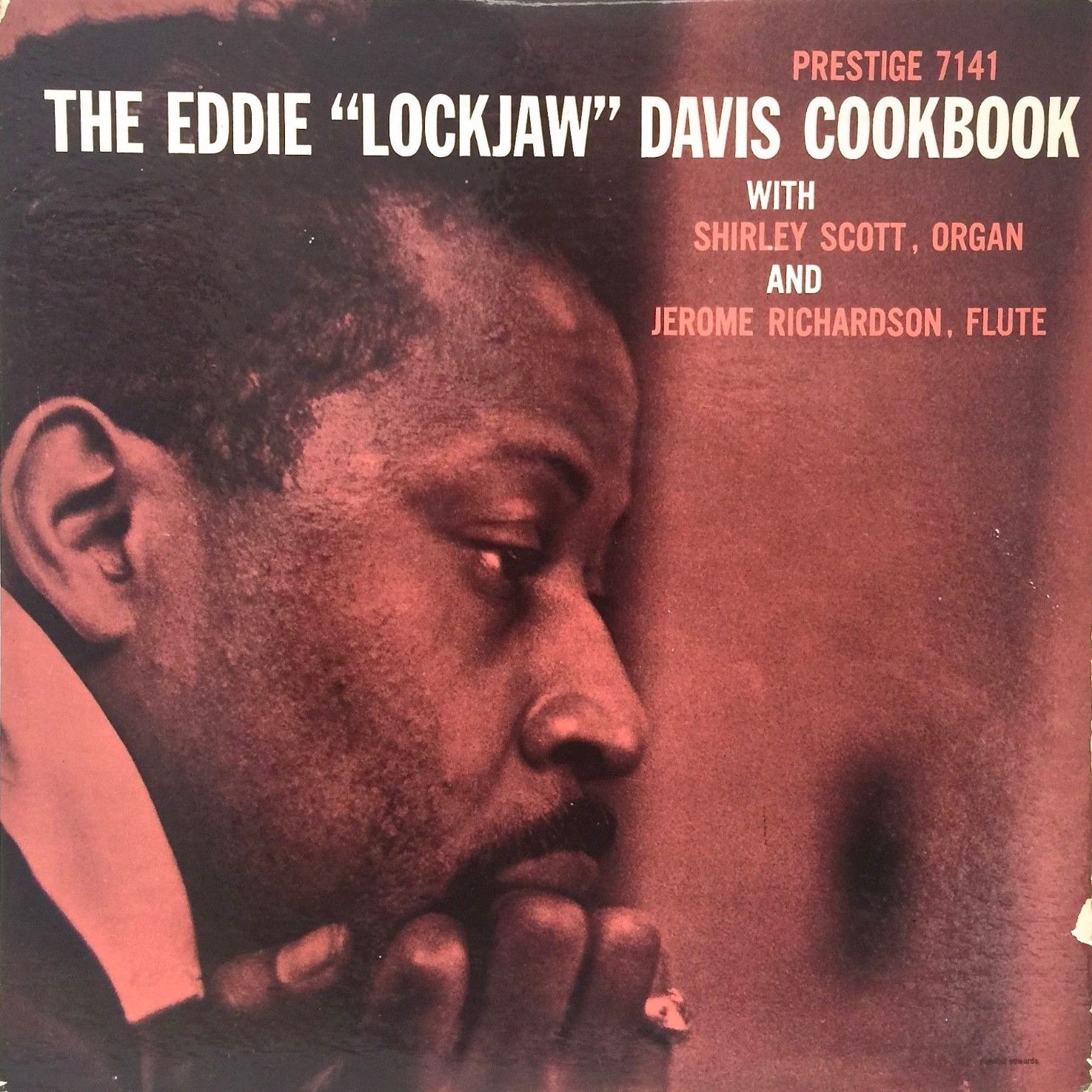

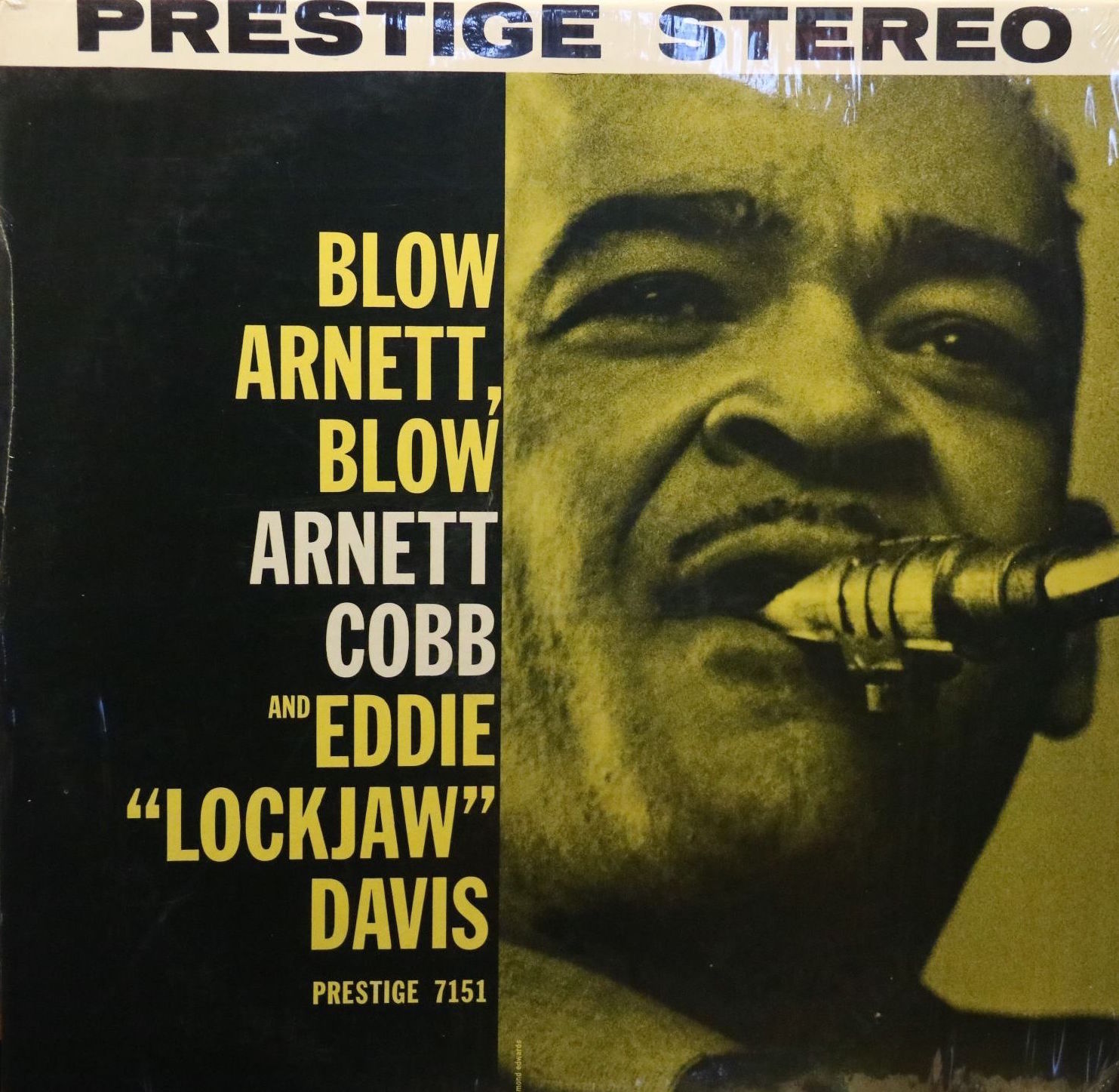

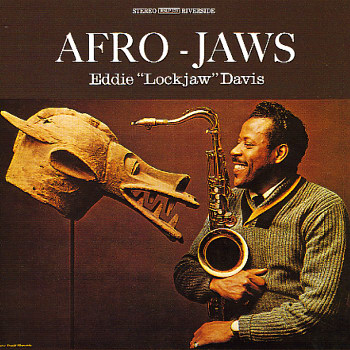

“Milan was great. That was my conservatory. The two best clubs were Capolinea and Due. I started out as a jack-of-all-trades. As well as playing I arranged replacements when somebody skipped a gig, translated contracts. Soon, I became a translator for many of those incoming legends who played at Capolinea. It was a great opportunity to be around those guys. Dexter Gordon, Buddy Rich, Tony Scott, Elvin Jones, Sonny Stitt, Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison, Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis… A great saxophonist, ‘Lockjaw’. Inimitable phrasing, powerful stories. Fantastic balladeer. When ‘Lockjaw’ Davis had a few drinks he played slow. Not as slow as Ben Webster when he was drunk, but medium slow. On the other hand, Sonny Stitt… He played Koko loaded. Really fast! And spot on! Reportedly, when asked how he managed to play when drunk, Stitt replied, ‘I practice drunk’! Some attribute that quote to Zoot Sims, but no matter who said it it’s a great story either way. Another priceless memory is seeing Gerry Mulligan perform. At the end of the night after the club closed he played with Tony Scott, both playing baritone, in the restaurant of the Capolinea jazz club. The drummer played brushes on an overturned spaghetti pan! Can you believe it?! Two in the morning and they played an unforgettable version of Body & Soul. I was soaking in all these great things that were happening to me. I translated for the Club and got paid with experience, so to speak.”

“Playing with Jimmy McGriff was exciting as well. Not only because McGriff is one of the great soul jazz organists, and a very sophisticated one at that, but also because it showed me how real jazz is – how it can communicate to an audience. I was in New York with Frank Grasso, to play and gain experience. We ended up in New Jersey at a small club. It was kind of a sleazy joint. There were some dangerous-looking people outside. But when I mentioned this to the owner he said not to worry and showed me a shotgun he kept under the bar.Welcome to America! McGriff liked us and invited us for a gig in Hartford, Connecticut. I said, ‘wow, that’s fantastic. I love your music. But… on one condition.’ ‘And that is?’, asked McGriff. I said: ‘That I don’t have to carry your Hammond B3 organ around!’ McGriff laughed. The reason was I almost got killed once carrying a Hammond organ up the stairs of the Pipers Club in Rome. McGriff’s van was like a bordello. A flophouse! Portable bar, lace all over, velvet, red wine-coloured curtains. The gig was great. Vintage soul jazz. The all-black crowd of army veterans and their families was having a wonderful time, shaking and dancing to our music.”

Guidi, a well-set man who walks slightly bent forward like an archeologist on Roman grounds and whose ironic and naughty grin brings to mind the elder Michael Caine, always stresses the value of entertainment in jazz. That’s why he’s such a big fan of Cannonball Adderley. “Ah, those live albums like Cannonball Adderley Quintet In San Francisco and At The Lighthouse. The atmosphere is so positive that you wanna be there! Cannonball is pure promotion for jazz! A great ambassador and communicator. I always tell my students to pick any one of Cannonball’s albums, especially from the late fifties and early sixties. If those don’t lure you to a jazz club, I don’t know what will! In this respect, I should also mention albums like Art Blakey And The Jazz Messengers’ Live At The Café Bohemia and Live At The Jazz Corner Of The World. And Free For All, also from Blakey. Not a live recording but the bible of hard bop! What controlled power, everyone in the band is cooking. Tubbs In New York, from the English tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes, is another cooker.”

“We shouldn’t forget that jazz always has had one foot in art, one foot in entertainment. That was made obvious by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Gene Ammons, Erroll Garner… too many to mention. Cannonball scored an enormous hit single with Jive Samba. A jukebox favorite for jazz fans, particularly in the black community. The message is that you don’t have to compromise, but always recognize that you are playing for an audience. The audience is smart, you know. People listen with their hearts. So if you want to touch them it helps to say something on stage. Even if it’s just a couple of words: communicate with the audience. Not everybody has the natural flair of Cannonball, but at least take notice of the audience. I don’t appreciate artists who don’t seem to care about the spectators and are playing just for themselves. Cecil Taylor did that. I respect a lot of free players for their excellence and vision, but at least try to explain something to the bewildered public. I saw Cecil Taylor empty a piazza at an open air jazz festival in Italy within ten minutes! I’d rather hear the indomitable Dexter Gordon telling the lyrics to What’s New to the audience before playing the theme. He did that with many tunes, he knew all the words to the songs. Chords are the roots of the plant, melody is the flower. But the lyrics constitute the perfume.”

“In addition to Cannonball’s charm, I’ve always loved his style. He’s a joyful player. You get the idea Cannonball was happy where he was. The flowers are blooming in the fields, bubbles are in the air. A whole different ball game than John Coltrane, whom I greatly revere as well. Two different sides of spirituality’s coin. Coltrane was always searching, never happy where he was. My favorite Coltrane albums? That’s easy. There are two albums that say, ‘here I am’. One is Giant Steps, with its harmonic daring and power. The other is Crescent where tracks like Crescent and Wise One define an arrival point for the deeply spiritual Coltrane. And the concise Bessie’s Blues is a gas. There’s nothing simpler than that blues theme. The essence of the blues. Just triads. But what he does with them… So pure, so simple, yet so deeply involved. Coltrane keeps ‘singing’ throughout. That’s something his imitators usually miss. They pick up on his harmonic theory and technique but they lack that spiritual cry. Really, do you know a more sincere quartet than Coltrane’s famous group with McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones? They’re so pure, like kids.”

Typical of Peter Guidi’s life story that an a-typical jazz instrument like the flute turned out to become his main jazz instrument. Guidi’s an incomparable flute historian that can tell you all about pioneers like the classical flutist Gazzeloni and the Cuban Alberto Socarras, who was one of the first to be recorded playing flute with a jazz band. Generally speaking the foundation of the modern jazz flute started with players such as Frank Wess in the Count Basie Orchestra and developed through the wonderful works of Sam Most, Eric Dolphy, Roland Kirk, James Moody, Herbie Mann and many others. “After hearing James Moody with the Dizzy Gillespie band, I wanted a flute. I love its lyrical, mystical quality. Aristotle already commented on the flute: ‘The flute is not an instrument that has a good moral effect. It’s too exciting.’ It only came into prominence once microphones came into the picture, providing the necessary volume to hold its own against reed and brass. Regardless of its relatively short jazz history, there have been, and are, so many fine players. The general public has likely heard of Herbie Mann. Although he did a lot of great bossa-nova material, I prefer players like Sam Most. Back then, you were either for Mann or Most. It’s like the Stones and Beatles. Fans of Herbie Mann would shout, ‘Mann Is The Most!’. Fans of Sam Most would reciprocate: ‘Most Is The Man!’”

Lest we forget, Guidi is a monster flutist himself who polished an excellent bop and mainstream jazz style while experimenting expertly with both the quarter tone flute and bass flute, vocalising, multiphonics, microtones and other modern techniques. Both as a leader and as a guest soloist, Guidi performed prolifically. “Not anymore, alas. The flute still stands beside my desk, I write a lot of compositions and I am planning a new CD release. But I don’t have a quartet anymore. Hey, until last year I led eight student ensembles and big bands, you understand? Busy! I must admit though, that I really miss performing in a quartet situation. But today there are so few places left to play.”

“So, anyway. What was your question? Haha!”

Peter Guidi

Peter Guidi (Glasgow, 1949) teaches at the jazz department of the Amsterdamse Muziekschool, where he is head of the jazz department. He is the bandleader of numerous youth orchestras such as Jazz Kidz, Jazz Juniors, Jazz Focus Big Band and Jazzmania Big Band, all of which have won a total of eighty-seven Dutch and international prizes. Mr. Guidi, associated with countless educational projects beside the Amsterdamse Muziekschool, was knighted as Ridder In De Orde Van Oranje-Nassau for his outstanding contributions to the Dutch jazz community in 2010. An acclaimed saxophonist and flutist, Guidi has performed and recorded prolifically, both in The Netherlands and at international festivals such as Umbria Jazz, Jazz Jamboree Warsaw and North Sea Jazz Festival. Peter Guidi lives in Amsterdam. His Jubilee Big Band will celebrate the 30th Anniversary of the Muziekschool’s jazz department, the 25th Anniversary of the Jazzmania Big Band and the 20th Anniversary of the Jazzfocus Big Band with a performance at North Sea Jazz Festival on July 8, 2017.

Selected discography:

A Weaver Of Dreams (Timeless, 1993)

Forbidden Flute (BMCD, 1999)

Beautiful Friendship (Timeless, 2000)

The Jazzmania Big Band – Further Impressions (with Benny Bailey, BMCD, 2004)

Jazz Focus Big Band – Focused, (JF, 2007)

Go to Peter Guidi’s website here.

Photography above: Ronaldus

Photography homepage: Ferry Knijn Fotografie