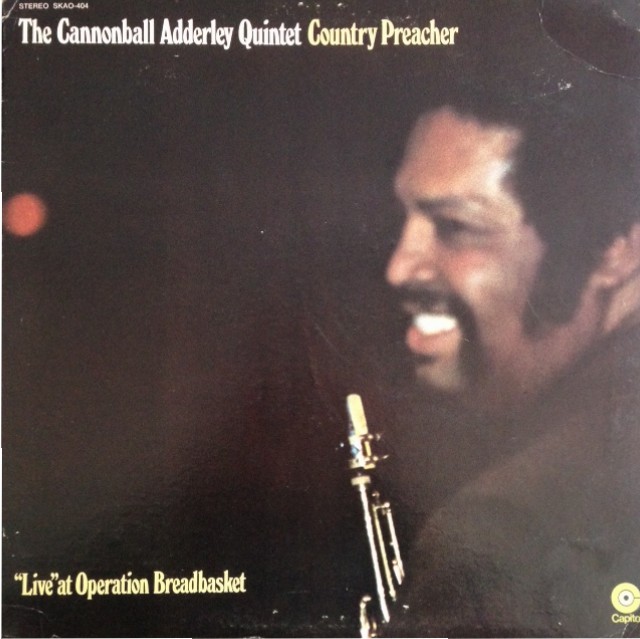

The hefty stew of boiling groovy thickness and powerful prayer meeting that is The Cannonball Adderley Quintet’s Country Preacher – Live At Operation Breadbasket is the climax in their book of epic live performances it began a decade earlier with In San Francisco and At The Lighthouse.

Personnel

Cannonball Adderley (alto saxophone, soprano saxophone), Nat Adderley (cornet, vocals), Joe Zawinul (electric piano), Walter Booker (bass), Roy McCurdy (drums)

Recorded

in October, 1969 in Chicago

Released

as Capitol 404 in 1970

Track listing

Side A:

Walk Tall

Country Preacher

Hummin’

Oh Babe

Side B:

Afro-Spanish Omelet

a.Umbakwen

b.Soli Tomba

c.Oiga

d.Marabi

The Scene

The fundamental premise of Operation Breadbasket was equal economic opportunity for the black community. Founded by Leon Sullivan in Philadelphia in 1962 and further developed by Martin Luther King in Atlanta, it negotiated jobs for people in the ghetto and strived to correct the perverse fact that industries sold product in black neighbourhoods but seldom offered decent positions besides menial labor. Boycotting companies was but one of the strategies of the persuasive core of black ministry. King appointed Jesse Jackson as leader of the Chicago department, which fell under the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. (SCLC) Chicago Breadbasket was a success, winning many new jobs. It also became a cultural event, inspired by the weekly Saturday sermons by Reverend Jesse Jackson. Jackson became the national director of Operation Breadbasket in 1967.

It was tangible. There was something in the air tonight. Cannonball, his voice a bit hoarse from a cold, his stomach presumably still digesting a copious meal, is up for the task. The band, simultaneously charged and relaxed, sits at the knees of the Reverend Jesse Jackson, who has provided a focused and fiery sermon, and subsequently is basking in the pleasure of hearing another exciting performance at an Operation Breadbasket meeting, in church in Chicago, and surely the most sizzling to date. The heat is on.

The Reverend, or the Country Preacher (the second tune of the album, Joe Zawinul’s Country Preacher, is dedicated to Jackson), was in full bloom in 1969, as can be heard on the quintet’s album on the Capitol label. Walk Tall is preceded by a spirited bit of sermonizing from Jackson, who can’t help spouting some painful, redeeming truths during his introduction of the band: ‘The most important thing of all is that, not matter how dreary the situation is, and how difficult it may be, that the storm really doesn’t matter until the storm begins to get you down, so I advice to you, the message The Cannonball Adderley Quintet brings to us, is that it’s rough and tough in this getto, a lot of funny stuff going down, but you gotta walk tall!, walk TALL!!, WALK TALL!!!’ Whereupon McCurdy, Booker and Zawinul put down a lurid boogaloo-ish groove, acted upon by the roaring unison brass and reed of Nat and Cannonball Adderley, a perfectly attuned imagination of the cathartic mirror Jackson held forth to the evening’s audience. The eloquent Cannonball, who also puts in a few strong-willed words, and the ambitious orator Jesse Jackson are a challenging match.

It is a match that raises questions too. Ever since the killing of Martin Luther King, Jesse Jackson, candidate for the Democratic presidential campaign in 1984 and 1988, has been a popular but controversial figure, perhaps never more so than immediately after that horrible event in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968. Although evidence was feeble, Jackson has always maintained the claim that he’d held the dying King in his arms, hence the blood on his turtleneck sweater. The turtleneck sweater controversy was born. A day after the murder of Reverend King, prime national spearhead of the black cause, Jackson appeared in a television show, wearing the bloody sweater and telling his story. King’s wife and close King associates, especially Ralph Abernathy, the former leader of the SCLC, were shocked and a schism in the SCLC and black power movement was a fact. The survivors and successors of the cause are fighting to this day, a shameful page in the story of black unity. Naturally, let there be no mistake, nothing should be taken away from Cannonball Adderley, who participated in the musical and socio-cultural event with the zest and goodwill we’ve come to associate with the amiable alto saxophonist. One keeps wondering though if Cannonball realized that, by embracing Jesse Jackson, the coldshouldering of Abernathy-and-friends was a logical consequence?

He definitely was conscious of his musical heritage. Prime ambassador for jazz, Cannonball had always been introducing the group’s music in humorous and insightful fashions, the initial introductions ten years earlier on the Live In San Francisco album functioning as a catalyst for soul jazz, or jazz for Chuck Chitlin & Big Mary (Bobby Timmons’ funky This Here the tune that got feet tappin’). In 1969, Cannonball again is the perfect host, elaborating concisely on the content of the compositions and the value of black music. As he succinctly and matter-of-factly explains during his introduction of the roaring 12-bar blues Oh Baby, ‘a soulful excursion into the past, the present AND the future of our music.’ It oozes pride for a truly American art form, a music born out of enslavement, degradation and misery, with a cast of legends that were unfortunately still unknown to most Americans. Perhaps he is not saying it very loud like James Brown, or anguished like Nina “Mississippi Goddamn” Simone, but the message is clear.

However, for the message to be clear, one has to think a bit further. Cannonball talks about black music. Assumingly, Cannonball, a streetwise, genial and intelligent personality, was of the opinion that black music is potentially inclusive, that at least a number of white men/women were able to play black music. One member of his group, Joe Zawinul, comes from Austria. Past member Victor Feldman was praised by Cannonball for his blues-infested skills. Cannonball’s cooperation with Bill Evans for the album Know What I Mean was one of his most gratifying experiences, not to say a major artistic achievement. In Evans’ case, surely Cannonball felt that something very distinctive was added to the music that had its origins in New Orleans. I’m guessing that Cannonball wouldn’t dispute the idea that whites had a distinct role in the development of jazz from the beginning. But he realized that the black experience intensifies the music, and that once you take away the core of jazz – the blues – you’re left with lifeless notes and tones. It was 1969, jazz had suffered blows, rock and pop reigned supreme, obviously Cannonball wanted to keep jazz real, fresh and energetic. Good job too!

By the way, not only the gig, all funk, sleaze, slow drag, tough swing and sparkling Afro-Jazz, is a wonderful exercise in rhythm, even these speeches by Cannonball move with a smooth, danceable beat. This way they have a penchant of seguing into the tracks, of which Spanish Omelet, an Afro-Cuban ‘suite’, is the longest by far, taking up most of side B. Structure-wise, it may not be so interesting, as it’s low on coherent motives, yet it’s the expressive force that somehow makes five parts a whole, from the lilting melancholy of Nat Adderley’s flamenco-ish Umbakwen, the singing, bended notes of bassist Walter Booker’s a capella Soli Tomba, Joe Zawinul’s hard modal funk of Oiga to the uplifting swingbop of Cannonball’s showstopper Marabi. Spanish Omelet is home cookin’, lively chatter in Erotic City, the brooding presence of hard-boiled Romeo, who stands on the corner, unfazed, bleeding from his elbow… It’s this kind of soul fusion (Adderley would delve deeper into bonafide fusion with 1971’s The Black Messiah and 1974’s Pyramid) that reduces the languid Bitches Brew by Miles Davis, recorded a couple of months before Country Preacher, to background music for spliff smokers.

Good news. The rest is just as sizzling. Jammin’ on one chord has seldom been brought to the fore so successfully as during Nat Adderley’s Hummin’. A slow groove built up by very heavy percussion and bass, Nat Adderley plays with the sureness of a customer who ends a bar row and subsequently has couples dancing with his tipsy singsong, spitting, coughing, growling, while Cannonball, on soprano, is like a fellow working the cottage doors with sandpaper, sweat on his back and brows, a couple of hours away from a refreshing bottle of beer. Oh Baby finds Nat Adderley in the limelight again, takin’ care of business singing the blues with a lurid sense of self-mockery.

Zawinul’s Country Preacher, a slow soul tune, is an exercise in tension and release, and the audience goes berserk, not unlike the responses Otis Redding, Solomon Burke, Sam & Dave, Ike & Tina or Aretha Franklin brought about. That’s the piece of land these fellows had staked out for themselves in jazz country. Country Preacher: Live At Operation Breadbasket is expressive, eloquent soul power. It’s pleasantly un-programmatic, possesses a let’s play in the sunshine-ish innocence, yet it’s solid as a rock. It doesn’t come any sleazier and real. A serious party.