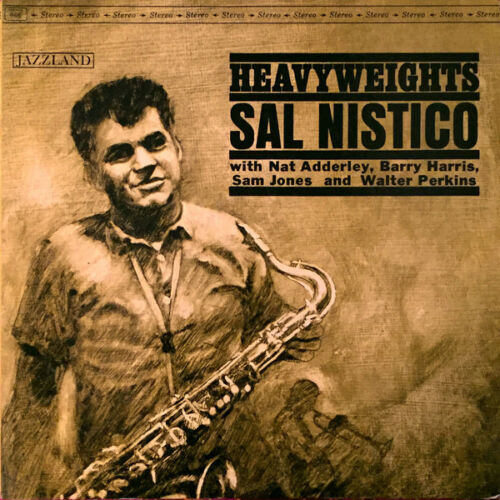

It may not have had widespread coverage, but Heavyweights was a thoroughly convincing declaration of independence by tenor saxophonist Sal Nistico.

Personnel

Sal Nistico (tenor saxophone), Nat Adderley (cornet), Barry Harris (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Walter Perkins (drums)

Recorded

on December 20, 1961 at Plaza Sound Studio, New York City

Released

as JLP 66 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Mamblue

Seconds, Anyone

My Old Flame

Shoutin’

Side B:

Just Friends

Au Privave

Heavyweights

During a conversation with fellow tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes in 1966, Sal Nistico said: “A lot of cats put down bebop, and they say it’s old and it’s dated, but that music’s not easy – It’s a challenge to play.”

The debut album of Nistico, 1962’s Heavyweights, made it sound easy, always a feat of accomplished players. When Heavyweights was recorded on December 20, 1961, Nistico, born in Syracuse, New York in 1941, had just left the Jazz Brothers Band of Chuck and Gap Mangione, which he had been part of since 1959. Nistico would come into prominence in Woody Herman’s Herd from 1962 to 1965. Nistico, who would furthermore play and record with Count Basie, Buddy Rich, Curtis Fuller, Dusko Goykovich, Hod ‘O Brien, Stan Tracey, Frank Strazzeri, Rein de Graaff and Chet Baker, enjoyed regular stints with Herman throughout his career, that came to an end with his passing in 1991 in Bern, Switzerland.

The strong line-up of Heavyweights furthermore consists of cornetist Nat Adderley, pianist Barry Harris, bassist Sam Jones and drummer Walter Perkins. The ensembles of Nistico and Adderley are fresh drops of water from the Spa source. Nistico is a hot, strong player, meanwhile keeping clarity of line, keeping the beat at a slightly laid-back pace, fiery and emotional yet convinced too of the power of understatement. Nat Adderley, very successful with the funky soul jazz work of the Cannonball Adderley Quintet in 1961, knows his bop, adding a delightful tad of sleaze to it with the muted sound of his cornet. Barry Harris, as always, is both magnificent as accompanist and soloist, contributing a number of masterful, Monk-ish statements.

Kickstarted by a fantastic mambo tune – Mamblue by Barry Harris – Heavyweights gracefully carries on the tradition of bebop, particularly Charlie Parker. The group performs Parker’s blues Au Privave, as well as My Old Flame and Just Friends, standards that are immortalized by Parker. Nistico’s Second’s, Anyone is a catchy bop line and Tommy Turrentine’s Shoutin’ a solid uptempo bebop performance. The unusual structure of the title tune, Heavyweights, penned by Frank Pullara, is reminiscent of Gerry Mulligan’s unique work. It’s a beautiful melody.

Straight-ahead excellence.