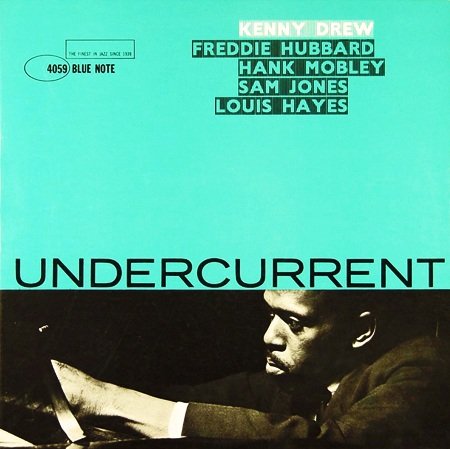

Kenny Drew’s Undercurrent isn’t called Undercurrent for nothing. The opener and title track is the pièce de résistance of the album in which every member of the band is on fire. Following it up with a set of excellent hard bop is quite an achievement.

Personnel

Kenny Drew (piano), Hank Mobley (tenor saxophone), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

Recorded

on December 11, 1960 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 4059 in 1961

Track listing

Side A:

Undercurrent

Funk-Cosity

Lion’s Den

Side B:

The Pot’s On

Groovin’ The Blues

Ballade

That hard bop was a development from bebop to more expressive playing of the down-home kind is true, but there was more to it. Near the end of the fifties, there were many different tastes. Pianist Kenny Drew, who played with Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins and Howard McGhee, among others, possessed his share of ‘funk’, but his touch was light as a feather, as opposed to the more common percussionist approach. Drew spun precise, logical but animated lines and was a fine accompanist, who worked extensively for Dinah Washington.

Drew’s blues tunes – Funk-Cosity and Groovin’ The Blues – are medium tempo groovers, distinctive for articulate, swinging Drew solo’s. The Pot’s On is a Horace Silver-type tune with an attractive old timey feeling. Lion’s Den (Obviously, Blue Note boss Alfred Lion’s pad) is a happy swinger that makes use of trademark hard bop interludes of suspended rhythm that boost the soloists considerably.

Ballade is a-typical for the period, eschewing double time or louder four/four-sections, instead opting for balanced, sweet and sour balladry. It’s charming.

Not only Kenny Drew, who wrote all six tunes, is in top form, Hank Mobley and Freddie Hubbard are spot-on as well. At the time, Hank Mobley, a young veteran of classic Art Blakey groups, had completed future classic albums Soul Station, Roll Call (including Hubbard) and Workout. Freddie Hubbard was a young, versatile lion who’d made a big impression on colleagues, recording his first two Blue Note albums in 1960 (Goin’ Up including Mobley) and appearing on dates of Tina Brooks and Eric Dolphy. He would appear on Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz ten days later on December 21 and join Art Blakey in 1961 for a stunning stretch of Blue Note and Riverside albums.

To complete the Blakey pedigree in this respect, Kenny Drew also played with the famed drummer and band leader, albeit for the shorter time of two months in 1957. However, Drew’s most renowned effort in that year is his work on John Coltrane’s imposing Blue Train album. Drew was part of many other sessions of the period, among them those of Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean and Kenny Dorham. Drew struck up a long association with Dexter Gordon onwards from the early fifties (Daddy Plays The Horn, Dexter Callin’, One Flight Up) and, like Gordon, became a longtime, widely acknowledged expatriate in Paris and, especially, Copenhagen. In a weird twist of fate Drew and Gordon even appeared in a Swedish, hippy-ish soft porn movie called Pornografi!

By then, about a decade had passed since Drew recorded the title track of this album. The partly modal theme includes the swirling arpeggios that aptly explain the sea-image title, which give an otherwise noteworthy composition even greater distinction. Best of all, the band is inspired almost beyond belief, with the essential inclusion of drummer Louis Hayes and bassist Sam Jones. Their experience as a rhythm tandem of many sessions of the day and Cannonball Adderley’s Quintet in particular stands them in good stead. They’re red hot, with a controlled intensity that would keep many a devil at bay. Louis Hayes’s temperature especially surpasses that of Lucifer with more than a few degrees!

The title tune is not only crisp and driving, it’s also full of immaculate solo work. Kenny Drew’s ideas keep flowing, his lines stretching over bars extensively. Mobley and Hubbard, triggered by Drew, Hayes and Jones, work up a sweat, and there are no parttime choruses. Mobley’s smoky sound and Hubbard’s buoyant style contrast pleasantly.

Undercurrent was Drew’s last album in the United States before he went to Paris in 1961 and settled in Copenhagen in 1963. Not a bad way to say goodbye to the American jazz life.