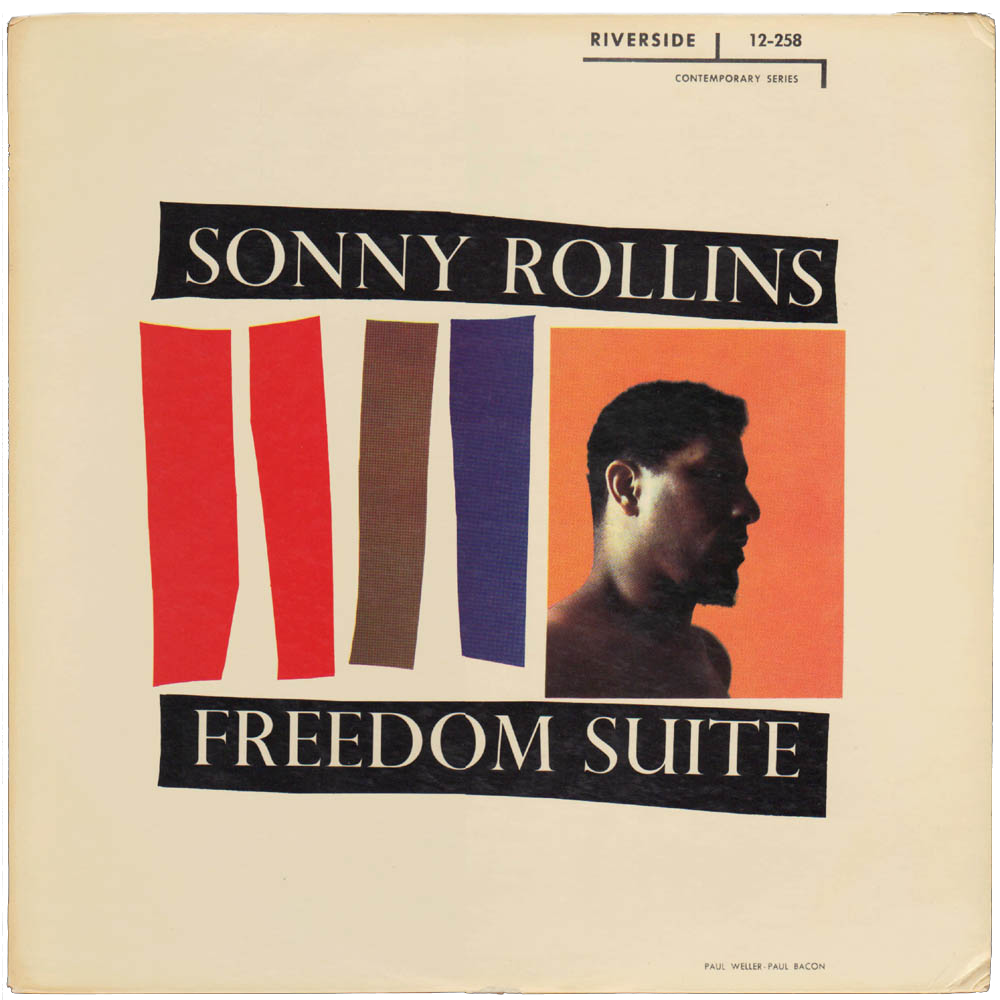

The title track of Sonny Rollins’ provocative 1958 album Freedom Suite takes up the whole of side A. Does anybody ever care to continue listening to side B’s set of Broadway and pop reworkings in one sweep? I would guess not. Notwithstanding the merits of those intriguing pop interpretations, the Freedom Suite is just too overwhelming. It begs to be relistened once the needle is off.

Personnel

Sonny Rollins (tenor saxophone), Oscar Pettiford (bass), Max Roach (drums)

Recorded

on February 11 & April 4, 1958 at WOR Recording Studio, NYC

Released

as RLP 12-258 in 1958

Track listing

Side A

The Freedom Suite

Side B

Someday I’ll Find You

Will You Still Be Mine

Till There Was You

Shadow Waltz

Nowadays, the place of Freedom Suite in the pantheon of influential musical statements of black consciousness is safe and secured. Back then, it was a bold stroke from a successful, innovative jazz artist who allegedly had trouble finding a decent apartment in New York City due to white racism. The message is hard to overlook. In the original sleeve notes, a statement from Sonny Rollins is included:

“America is deeply rooted in Negro culture: its colloquialisms, its humor, its music. How ironic that the Negro, who more than any other people can claim America’s culture as its own, is being persecuted and repressed, that the Negro, who has exemplified the humanities in his very existence, is being rewarded with inhumanity.”

The image of Sonny Rollins on the front cover might be explained as the visual companion to his written words. Rollins, half-naked, cast in shadows, with a hurt, yet defiant countenance, looks purported to resemble a slave. It connects with the parts of the suite that bear an eerie resemblance to chain gang songs.

First and foremost, Sonny Rollins lets the music speak for itself. The Freedom Suite (the title track) combines the harmonic daring and fervent drive of Rollins and the controlled fire and melodic finesse of his companions Max Roach and Oscar Pettiford. It’s built on three movements of similar, short melodies and fascinates from start to finish. In the opening melody, a tacky, jingle-like cluster of phrases that show Rollins’ affinity with the playful, quixotic themes of Charlie Parker, Rollins takes seven minutes to explore every angle of the melody. Pushing or pulling the beat, veering between registers by way of an assertive flurry of arpeggio’s, Rollins glues together heartfelt sweeps and humorous asides. Oscar Pettiford sternly pushes along the loping rhythm. Max Roach concentrates almost as much on melody as Rollins; constantly favouring snare and toms above cymbals, Roach ferociously mirrors the instant gems Rollins cooks up. It’s a spontaneous, exciting group performance.

After a pause, the trio sets in the rollicking theme that sounds like a chain gang or slave boat song. Paradoxically, it also has the giddy-up bounce of a cowboy song. Via a couple of a capella Rollins phrases, it segues into a beautiful ballad. It’s not a blues, but blues feeling is at its core. The husky delivery of Rollins is supported succinctly by Roach and Pettiford. They take plenty of room, as in the first movement, to display their excellent solo qualities. Roach and Rollins shared a lot of experience, having collaborated in the Max Roach/Clifford Brown quintet and on a couple of Rollins albums, among them the landmark album Saxophone Colossus.

After another chain gang bounce intermezzo, Rollins thrusts himself headlong into a short melody at breakneck speed. It’s the Sonny Rollins of Live At The Village Vanguard 1 & 2, elaborating on bebop principles with fresh, harmonic elan. The near-anarchic Rollins is in top form, beginning and ending phrases where you least expect them to. The piano-less endeavor has clearly worked in Rollins’ favour. Freedom Suite possesses a rugged beauty. Before Freedom Suite, Rollins had recorded succesfully with piano-less trio’s on Way Out West and the beforementioned Village Vanguard albums. He would continue displaying his fascination for the format with The Bridge in 1961.

Rollins is admired for his knack of finding and transforming often obscure Broadway, Tin Pan Alley and pop melodies. The interpretations on Freedom Suite have that typical Sonny Rollins sound of surprise, but lack the bliss of renditions such as There’s No Business Like Show Business (from Worktime) The production doesn’t work in his favor as well. The sound of the rhythm section is pretty flat and dry – listening to Max Roach cardboard box sound, one feels inclined to assume that it must’ve been Riverside’s objective to re-create the demo sound of a live gig at Minton’s Playhouse in the late fourties.

Of these reworkings, Will You Still Be Mine is the most interesting. The intricate rhythm work of Roach and Pettiford intensifies the mood of Rollins, who reacts with an extravagant climax. The call and response between Rollins and Roach on Someday I’ll Find You is an attractive asset to a pretty melody. Till There Was You – also recorded by The Beatles in 1962 – is a sax-bass duet for the biggest part. Rollins succesfully avoids its corny character. The only time Sonny Rollins doesn’t seem up for his task is on Shadow Waltz. He sounds detached, unable to get under the skin of the melody.

Sonny’s statements in the sleeve notes ring through. Both daily life (housing, employment) and law (the victory of Brown vs Board Of Education backfired) still put blacks in disadvantage around 1958. Racism persisted around the country. A disproportionate number of poor blacks had died in the Korean war. But being a musician, being the continuously inventive Sonny Rollins, the music of Freedom Suite is what speaks most eloquently. Rollins doggedly met the challenge of the experimental title track and showed what jazz is all about.