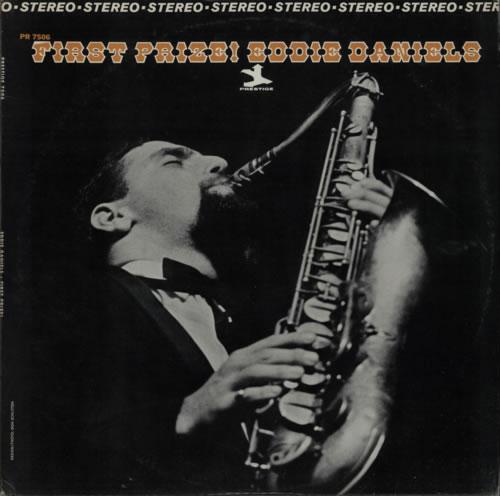

Eddie Daniels is a jazz saxophonist who turned into a master of classical music. Or no, Eddie Daniels is a concierto clarinetist who played modern jazz with the best of his generation. Well, yes on both counts but not exactly… At any rate, his 1967 recording debut as a leader on Prestige, First Prize, is a monster album.

Personnel

Eddie Daniels (tenor saxophone, clarinet), Roland Hanna (piano), Richard Davis (bass), Mel Lewis (drums)

Recorded

on September 8 & 12, 1966 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7506 in 1967

Track listing

Side A:

Felicidad

That Waltz

Falling In Love With Love

Love’s Long Journey

Side B:

Time Marches On

The Spanish Flee

The Rocker

How Deep Is The Ocean

Born in Brooklyn, New York City in 1941, Eddie Daniels started on alto at the age of 9, then studied clarinet on Juillard at 13. Daniels also mastered the tenor, soprano and baritone saxophone, as well as the flute. His first professional job was on tenor saxophone with clarinetist Tony Scott at the Half Note in the fall of 1965. Daniels filled a sax chair in the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra in the late sixties and early seventies, but it was on clarinet that Daniels first gained recognition as part of that highly acclaimed group, winning Downbeat Magazine’s New Star On Clarinet competition in 1966. Daniels developed into a virtuoso of both jazz and classical music, a rare accomplishment. Accolades from a certain duo of renowned ‘Leonards’ comprise ample proof of Daniel’s reputation:

Leonard Feather: ‘It is a rare event in jazz where one man can all but reinvent an instrument bringing it to a new stage of revolution.’

Leonard Bernstein: ‘Eddie Daniels combines elegance and virtuosity in a way that makes me remember Arthur Rubinstein. He is a thoroughly well-bred demon.’

Daniels was a sought-after player who was part of, subsequently, the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra from 1966-72 and the Bobby Rosengarden Orchestra, the house band of the Dick Cavett Show, from 1972-78. Onwards from the eighties, Daniels concentrated more and more on his clarinet work in classical music. His jazz discography includes side dates on Dave Pike’s The Doors Of Perception, Freddie Hubbard’s live album The Hub Of Hubbard, Don Patterson’s The Return Of Don Patterson, Yusef Lateef’s Ten Years Hence and George Benson’s Benson & Farrell. As a leader, Daniels followed up First Prize with the Japanese Columbia album This Is New. Further albums include A Flower For All Seasons, his 1973 cooperation on Choice with guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, with whom Daniels would build a life-long association, 1988’s Memos From Paradise and 2013’s Duke At The Roadhouse.

In 1966, Daniels also won The International Competion For Modern Jazz on saxophone in Vienna, Austria. Hence, presumably, the title of his debut album. On First Prize, Daniels is supported by the rather unbeatable rhythm crew of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Mel Lewis, Richard Davis and Roland Hanna. Daniels is quite impossible to beat himself. A strong, alternately breathy and piercing tenor sound, which occasionally goes up to the alto register, facilitates an exuberant, flexible style that brings to mind Sonny Rollins and, to a lesser extent, John Coltrane. Clearly in utter control of the tenor, clearly laboring with love, Daniels playfully juggles with tender swing-era whispers and behind-the-beat slurs, perfect legato sections and ferocious forward motion flights and sheets of sound.

Latin-type tunes, like Felicidad and The Spanish Flee, start tenderly and breathy and end up squeezed out like blocks of oak wood in a shredder. It’s overwhelming, not so much because Daniels is showing his fists, but instead is in perfect command of his ferocity. The section in Felicidad in which the tumbling notes of Daniels ricochet off Hanna’s percussive chords is particularly enamouring. Just as well, Daniels relishes standards like Falling In Love With Love, developing a striking contrast between a partly slurred, rubato theme and a hi-octane bebop solo. Hanna chimes in with chubby, Silver-type chords and flowing right hand lines that reveal a definite liking for Bud Powell. The brush work of Mel Lewis carries the tune, it’s steady, holding in check toying Mr. Daniels, while simultaneously providing an almost ethereal sound carpet, like a lake of gentle gulves that roll upon the shore. Throughout the album, the rhythm trio is obviously having fun on a very high musical level.

On clarinet, Daniels is ambidextrous and imposing. Time Marches On employs a classical (overdubbed) theme, seguing into a gentle bossa tune. The Rocker reveals Daniels’ ability to bebop on the instrument, as he fills the uptempo burner with notes that bounce to and fro, much like pinballs that race through the limetless little halls and creviches of an Escher drawing. The organic, wooden sound of the clarinet and the lyrical and muscular lines of Eddie Daniels bring added depth to an album that was already very impressive as a modern tenor sax job. An overwhelming debut.

First Prize is not on Spotify or YouTube. however, Daniels’ version of John Coltrane’s Giant Steps from his second album, This Is New, (listen here) gives a good impression of his mastery of the tenor saxophone. Also on YouTube are a number of instructions that Eddie Daniels gave a couple of years ago as an endorser for Backun. Hear Eddie talk about the blues here, speed and agility here and his dexterity on reed, clarinet and woodwind here. Confident, witty, flexible, just like his music. A handsome man to boot, could’ve been George “Rosemary’s Nephew” Clooney’s older brother.