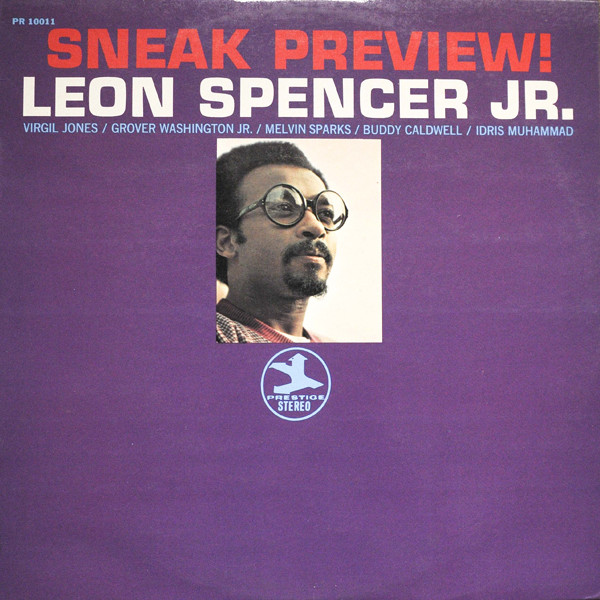

If you like your groove greasy as kidney stew and gritty as a walk with dinosaurs on a gravel path, Leon Spencer Jr.’s Sneak Preview is the way to go.

Personnel

Leon Spencer Jr. (organ), Grover Washington Jr. (tenor saxophone), Virgil Jones (trumpet), Melvin Sparks (guitar), Idris Muhammad (drums), Buddy Caldwell (conga)

Recorded

on December 7, 1970 at Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 10011 in 1971

Track listing

Side A:

The Slide

Someday My Prince Will Come

Message From The Meters

Side B:

First Gravy

5-10-15-20

Sneak Preview

The Slide will take you for a ride. Leon Spencer’s opening tune, just like his album on which it was presented early in 1971 on the Prestige label, Sneak Preview, is a vintage gritty Hammond B3 killer. Recorded at Rudy van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Van Gelder not only shaped modern jazz with his engineering for Blue Note and other labels, he was also a fundamental force in making organ jazz an viable musical experience and an accessible, marketable product, initially through his cooperation with Jimmy Smith in 1956. Managing to tame the monster machine’s belligerent tendencies and bringing to the fore crisp, clear lines while retaining the church-rooted feeling, sonority and indomitable oscillating sounds, Van Gelder set the standard for future engineers to follow. In the late sixties and early seventies, RVG was still at it, taking care of virtually all the Prestige funk jazz releases.

Such as Sneak Preview, the sound of molasses, chili in a bowl and ham-on-rye on master tape, which is transferred to the black gold that is still to be enjoyed here and now, in 2018, preferably on original wax, though the OJC reissue is doing a job well done, thank you. Forget the screen of your iPhone for a minute, put the disc on the turntable, kick yourself into gear and slide into the world of sensual, chubby thighs exposed at the stools of sleazy, sweaty bars, of hallelujahs shouted from tiny BBQ joints, of the unstoppable toes that wear out the streets of Baltimore, Harlem’s Lenox Avenue, the wooden floors of Lenny’s-On-The-Turnpike until nothing’s left but dusty remains not unlike the bones of long-gone Victorian maidens… Chill. Zen And The Art Of Turntable Maintenance.

Leon Spencer Jr. gets you to that place. Spencer’s discography is rather concise, but the level of excellence and deep groove is on par with contemporary colleagues like Lonnie Smith and Charles Earland. Spencer came into prominence a few years later. He was born in Houston, Texas in 1945, started out on piano and performed with his friend David “Fathead” Newman as a young man. Spencer studied engineering at Texas Southern University and the University Of Houston and subsequently toured with Army bands. Like many organists, he took up the organ after seeing Jimmy Smith and soon backed Peggy Lee and Lou Rawls. He made his debut in 1969 on guitarist Wilbert Longmire’s Revolution album on World Pacific while living in Los Angeles. Spencer played on guitarist Melvin Sparks’ Sparks and was featured on Lou Donaldson’s Pretty Things album on Blue Note in 1970, which made his reputation as a bonafide jazz funkateer. After Sneak Preview, Spencer would perform on another Donaldson album, Cosmos, another Sparks album, three Sonny Stitt albums and Rusty Bryant’s Fire Eater. As a leader, Spencer followed up Sneak Preview with Louisiana Slim, Bad Walking Woman and Where I’m Coming From.

Sneak Preview used the same line up as Sparks. And the group would work together on Stitt’s Turn It On as well. Some of the members had already cooperated here and there, like Muhammad, Virgil Jones, Melvin Sparks and Buddy Caldwell on Muhammad’s Black Rhythm Revolution on November 2, 1970, or Muhammad, Jones and Sparks on Rusty Bryant’s Soul Liberation on June 15, 1970. I’ve grown accustomed to your face… Standard Prestige procedure (and Blue Note, of course, for that matter): The more tight-knit a group of like-minded fellows and dames become, the smoother the session will develop. This group, consisting of Spencer, trumpeter Virgil Jones, tenor saxophonist Grover Washington Jr., guitarist Melvin Sparks, drummer Idris Muhammad and conga player Buddy Caldwell, has no trouble getting to the nitty-gritty before the lights go out. Idris Muhammad’s drive, as usual, is relentless. There really can be no end to the amazement for the listener of Muhammad’s snappy single snare strokes before-the-one and his firm accompaniment with bass pedal, hi-hat and cymbal. We hear Grover Washington before the saxophonist hit the big time with smooth jazz in the early seventies, and he’s keeping it real and rootsy. And small wonder that A&R man Bob Porter regularly called Virgil Jones for sessions like these, he’s virile, acute, excellent. Virgil Jones is a player who’s all but forgotten, undeservedly.

The group performs Spencer’s funky blues The Slide, shuffle groove First Gravy and the tacky, modal vamp Sneak Preview, Someday My Prince Will Come, the hit from The Presidents 5-10-15-20 and a funk groove from The Meters, Message From The Meters. The latter’s the highlight, a crazy funky affair with intense storytelling from Spencer. Spencer’s bass work (presumably a mix of left hand and a bit of feet) is striking, not only during Message, but also during the popsoul gem 5-10, weaving snappy lines in the middle register into the mix.

Leon Spencer passed away in 2012.

Listen to the full album on YouTube here