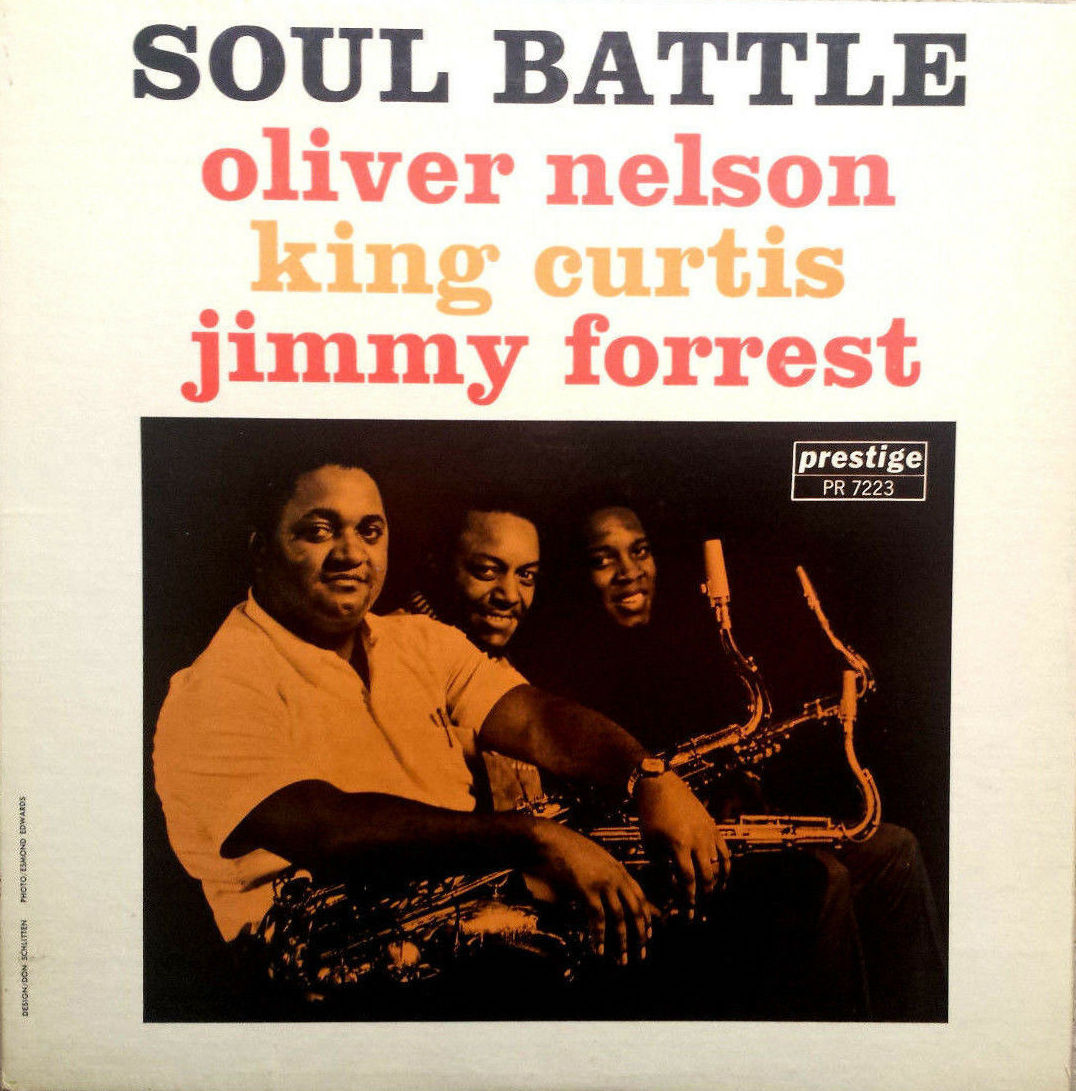

Oliver Nelson had a knack for interesting parings of horns and Soul Battle is a seriously entertaining combination of the differing tenor styles of Nelson, Jimmy Forrest and King Curtis.

Personnel

Oliver Nelson (tenor saxophone), Jimmy Forrest (tenor saxophone), King Curtis (tenor saxophone), Gene Casey (piano), George Duvivier (bass), Roy Haynes (drums)

Recorded

on September 8, 1960 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PRLP 7223 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Blues At The Five Spot

Blues For M.F. (Mort Fega)

Anacruses

Side B:

Perdido

In Passing

It is easy to overlook the beauty of a saxophonist’s voice and hi-level playing style when the player in question is also known, perhaps better-known, through his exceptional work as a writer and arranger. Benny Golson is a case in point. Oliver Nelson certainly qualifies. Evidently, he was a renowned arranger of his own work but mostly of other artists like Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Cannonball Adderley, Wes Montgomery and Jimmy Smith. His body of work as a writer is comprehensive and filled with gems, the achingly beautiful Stolen Moments serving as his undisputed masterpiece.

Obviously, Blues And The Abstract Truth, his album on Impulse from 1960 which included Stolen Moments and featured Eric Dolphy, Freddie Hubbard and Roy Haynes, is a stone-cold classic and a perennial favorite among teachers at conservatories around the world. Standard subject matter. Straight Ahead isn’t such an indelible part of the curriculum, undeservedly. It’s an essential date on par with Abstract. Strikingly, Nelson’s Prestige albums of this period, which began in 1959 with Meet Oliver Nelson, consist of a thoroughly convincing effort to interpret the blues. Oh boy, his gelling with Dolphy – Dolphy playing Charlie Parker backwards, flying out there, Nelson more modern in the conventional sense, plaintive yet forceful – is truly something else.

Soul Battle precedes Blues And The Abstract Truth and Straight Ahead, which were recorded in the winter of 1961. If the latter albums are blues-based recording sessions that are simultaneously spontaneous and proof of careful preparation, Soul Battle is best described as a relaxed but driving, good-old blowing session. Count your blessings, this is a tenor battle royale! We have Nelson, employing a tone that often touches the alto register, on the hunt for ideas all the time, finding them too, carefully placing them in orderly fashion yet eager to move on, light-footed like a deer in the wild…

Then there’s Jimmy Forrest. Forrest goes way back, played on the riverboats of Mississippi with Fate Marable, with Duke Ellington, became an overnight r&b one-day-fly with Night Train in 1952 (a tune that was based on Duke Ellington’s Happy-Go-Lucky-Local), played with St. Louis pals Miles Davis and Grant Green and spent a big part of the seventies in the band of Count Basie. He’s putting some serious jazz history in a session like this. Take a listen to Blues For M.F., an excellent jump blues that has Nelson taking first solo, expertly so. Then Forrest hits four B.I.G. archetypal notes straight from Coleman Hawkins and suddenly Roy Haynes falls into a pocket… and an even deeper groove that was already developed is a fact… We have King Curtis, the r&b-star. However, lest we forget, King Curtis was a solid jazz player. His hard-edged tone, sleazy phrasing and fervent wails present a nice contrast with Nelson and Forrest’s subsequent modern and rootsy concepts.

Nelson’s story of Anacuses, one of four Nelson originals on Soul Battle – Juan Tizol’s Perdido the exception – has the passion and intensity of Coltrane, the hard-boiled flexibility of Joe Henderson and the direct emotional impact of Booker Ervin. Take that! A thorough dive into Oliver Nelson’s discography will find many exceptional moments, he’s truly one of the greatest saxophonists of his generation.