From sitting at the feet of her grandmother and the turntable as a toddler in Osaka to jazz mecca New York and the international stage, organist Akiko Tsuraga has come a long way, still thriving on the inspiration from mentors Lou Donaldson and Dr. Lonnie Smith. “I’m trying to do as they did as much as I can, which is playing for the people first and foremost.”

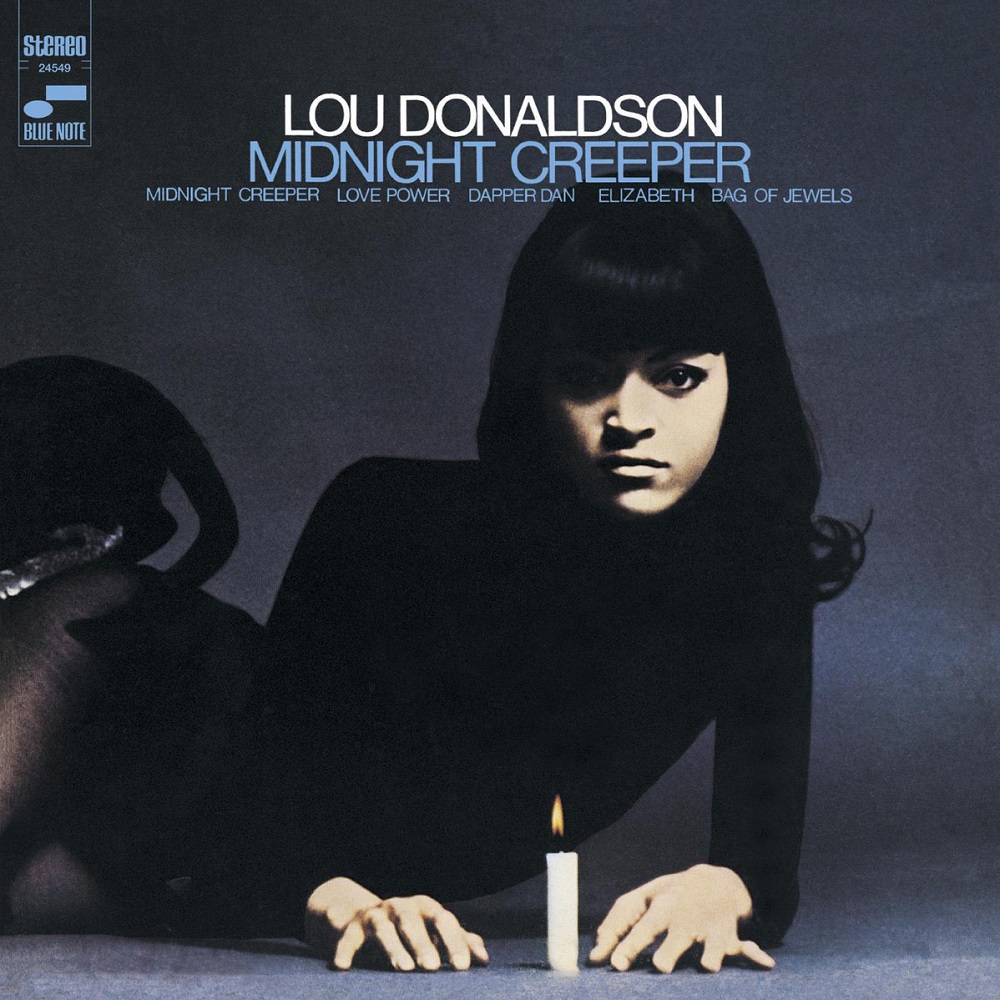

She keeps staring into space. At a point beside the screen where, it seems, a dehydrated spatula has fainted while walking to the faucet on the kitchen counter. Then she simply says: “I miss him so.”Tsuraga refers to alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson, who passed away on November 9, 2024, at the venerable age of 98. She was part of Donaldson’s organ group for many years, heir to a line of illustrious forerunners that includes Lonnie Smith, Baby Face Willette, Big John Patton, Charles Earland and Leon Spencer.

A while later, while discussing her entrance in the New York scene in 2001 – troubled and tragic times in American history – Tsuraga falls silent again. When she has regained her posture, she explains that, without denying how horrible the WTC disaster was, she already knew all about tragedy, referring to the horrendous earthquake in Kobe, Japan in 1995.

Humble Tsuraga goes for content instead of verbosity, ‘less is more’ instead of waterfalls of words. No mistaking, she offers plenty expression and often exhibits her typical laughing mood, laced with delicate twists of consent, puzzlement, unease and enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is the mood that she carries to the stage, where she oozes joy and where her notes laugh like kids in the playground and smile like grandparents sitting at the curb of the sandbox. The Osaka-born organist is a fixture on the New York scene, collaborating frequently with stalwarts as saxophonists Jerry Weldon and Nick Hempton, guitarist Ed Cherry and, not least, her husband, ace trumpeter Joe Magnarelli. Tsuraga released seven albums as a leader on various labels. Her latest is Beyond Nostalgia on Steeplechase. She doesn’t rest on her laurels and recorded a new album with drummer Jeff Hamilton, to be released in 2025. In May, Tsuraga hits the studio in Vancouver for a recording with the Vancouver Jazz Orchestra, a future Cellar Music release.

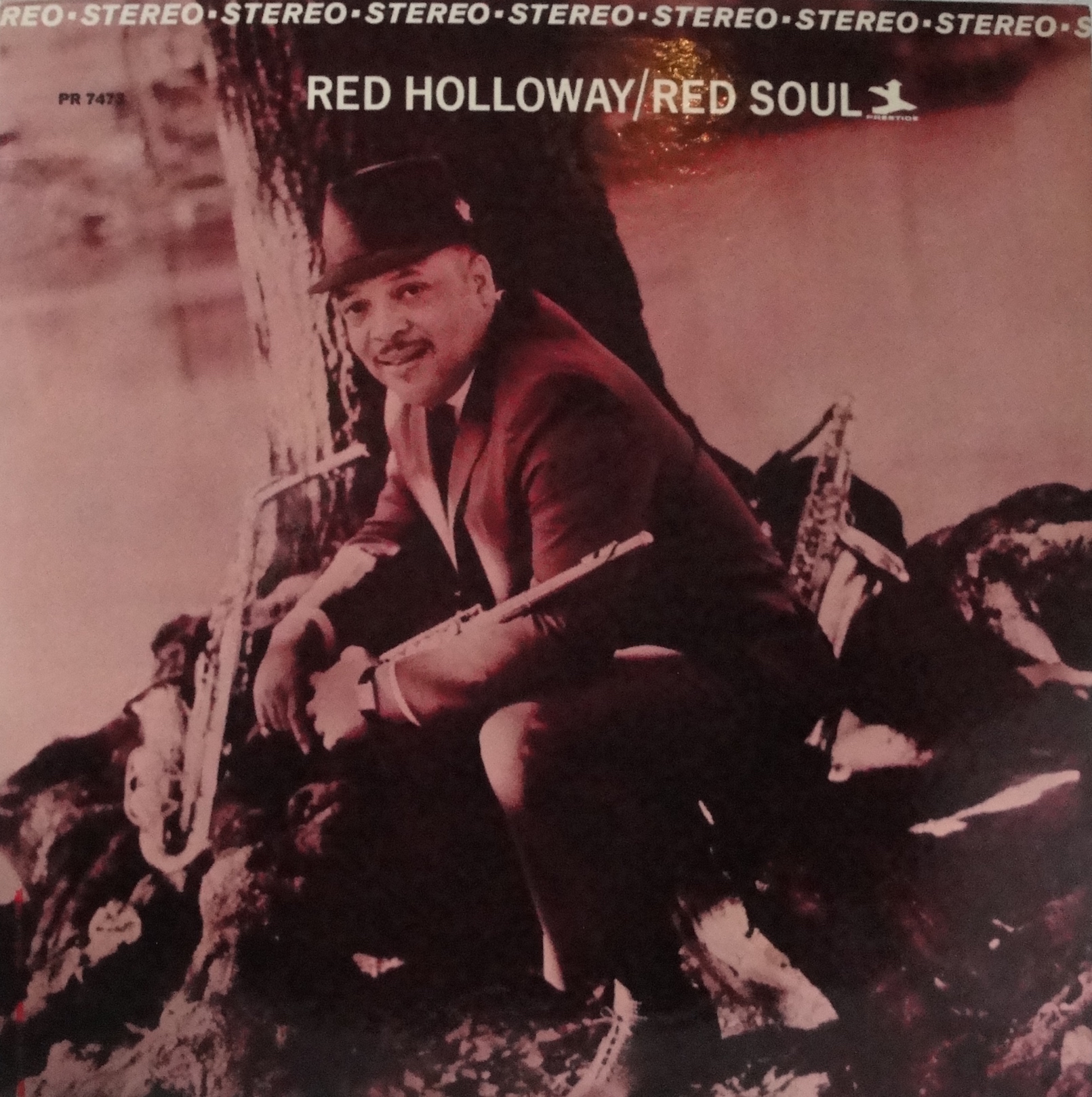

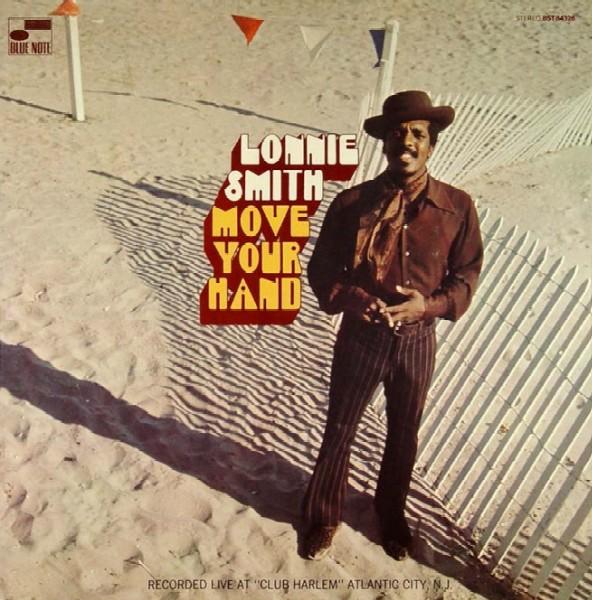

New York City remains home base, the Bay Ridge area in South Brooklyn to be precise. Her unlikely journey from Osaka to the jazz heart of The Big Apple is a curious mixture of talent, perseverance and pivotal encounters with the cream of the classic jazz crop. “Before I went to New York, I was working in clubs in Osaka. I used to play at an after-hours-club across the street from the Blue Note Osaka club. Many musicians who played there stopped by after their gigs. The after-hours-club had a Hammond B3 organ. I met so many people and had a chance to play with Grady Tate, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Brother Jack McDuff, Jeff “Tain” Watts, Kenny Kirkland, Joey DeFrancesco, Larry Goldings, Earl Klugh.”

She continues: “I was already very good friends with my mentor (drummer, FM) Grady Tate in Osaka. When I started out in New York, he helped me out a lot, showed me around places and introduced me to people. Dr. Lonnie Smith helped me in similar ways. I’d met him through drummer and mentor Fukushi Tainaka, who also introduced me to Lou Donaldson. I went to the Showman organ club in Harlem every week and met Jerry Weldon for the first time. Eventually, the club gave me a gig. When Dr. Lonnie left Lou’s group (After Smith’s tenure with Donaldson’s group in the mid-1960’s, he reconnected with him for many years the 1990/00’s, FM), Dr. Lonnie and Fukushi recommended me. Lou came to the Showman and after the first set he said, ‘Ah, Akiko, you’re so brave! Coming to New York by yourself! And you sound better than any male organist around New York.’ Lou said that I needed to learn how to comp behind horn players and that he was going to teach me. We played all over the world, long tours in Europe, Japan and on American festivals. It was an unforgettable experience.”

A far cry from her youth in Osaka. Though, that’s disregarding the Japanese fascination with Western/American culture in the 20th century, regardless of world wars. Tsuraga: “My grandmother was a big jazz fan. I heard many jazz records that way. And I loved the sound of the organ. My parents bought me a Yamaha organ when I was three years old. I started taking piano lessons as a kid and studied at Yamaha Music School. I got the chance to play all sorts of music there, American popular music, jazz, fusion.”

Plenty reason for nostalgia. But Tsuraga, as her latest album reveals, rather looks beyond nostalgia, without forgetting the richly layered roots of organ jazz. Beyond Nostalgia is an unabashed variation of organ themes. Sassy swinging modern jazz originals like Tiger alternate with the old-timey reenactment of Mack The Knife. The souped-up What A Difference A Day Makes is counteracted by the relaxed shuffle of The Happy Blues, which precedes the modal album highlight, Middle Of Somewhere, conceived after an ice-fishing trip with a friend in Wisconsin. The title track is a lovely mood piece. What’s the story behind Beyond Nostalgia? “I wrote that song after I visited the temple in Kyoto. I went with my sister. It’s a very spiritual place. It was such a beautiful experience, we were crying. Birds were humming and suddenly that melody came to me. The temple is the birthplace of ‘reiki’, hand-healing.”

Tsuraga has been involved with reiki for a long time. “I love it. Since I followed classes, I started to realize that when I play organ, my fingers feel much stronger and more sensitive. I love that feeling. You know, Dr. Lonnie Smith had really powerful hands. He would unintentionally break Iphones and Ipads! A friend of mine who works at Apple says that people with exceptionally strong hands sometimes break those screens. I was thinking, if I have the same power, my playing will improve and be just like Dr. Lonnie’s!”

She tells it with one of her enticing variations of laughs, part apologetic, part matter-of-factly packaged see-what-I-mean. It’s easy to see what she means with her final remark, though it must be said that by now her playing is nothing less than Tsuraga’s.

Akiko Tsuraga

Check out the website of Akiko and her discography here: https://www.akikojazz.com/

Find Beyond Nostalgia on certain questionable streaming platforms and buy here: https://propermusic.com/products/akikotsuruga-beyondnostalgia?srsltid=AfmBOorPIlRfkJg11PhWiXg9g46V_UJTY51Wsevzpl7lcGaBlvLlWiLT

Picture header: Joseph Berg.

Picture 1-3: Lou Donaldson & Akiko; Akiko & Lonnie Smith; Akiko & Jerry Weldon