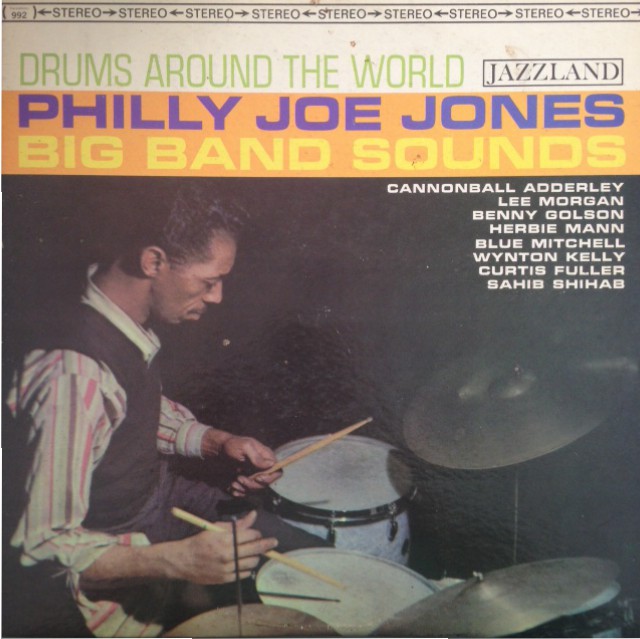

Whether you decide to call it Drums Around The World or Big Band Sounds, the star-studded second record of Philly Joe Jones on Riverside is a blast from start to finish.

Personnel

Philly Joe Jones (drums), Lee Morgan (trumpet), Blue Mitchell (trumpet), Benny Golson (tenor saxophone), Cannonball Adderley (alto saxophone), Sahib Shihab (baritone saxophone), Curtis Fuller (trombone), Herbie Mann (flute, piccolo), Wynton Kelly (piano), Jimmy Garrison (bass), Sam Jones (bass)

Recorded

on May 4, 11 & 28, 1959 in NYC

Released

as RLP 12-302 in 1959

Track listing

Side A:

Blue Gwynn

Stablemates

El Tambores (Carioca)

Tribal Message

Side B:

Cherokee

Land Of The Blue Veils

Philly J.J.

Get in the driver’s seat and take a listen to Philly Joe Jones and his sparring partners of May 1959, a who’s who of the hard bop era: Lee Morgan, Blue Mitchell, Benny Golson, Cannonball Adderley, Sahib Shihab, Curtis Fuller, Herbie Mann, Wynton Kelly, Sam Jones and/or Jimmy Garrison. Perfect foil for Philly Joe Jones’s vision of showcasing varying rhythms of the world. In the process, Jones made a record that sustains momentum throughout.

All Music, with the devoted indifference of the call center employee, says: “There is some strong playing but this set is primarily recommended to fans of Philly Joe Jones’s drum solo’s.”

There is but one punishment for people who keep uttering the word ‘recommended’. And that is to look at the cover of Herbie Mann’s Push Push for 24 hours straight.

Big Band Sounds is not an ego trip. Philly Joe Jones is part of the pack, who indeed briefly displays his prowess as a soloist, but most of all takes care to lead his buddies through a sublimely paced set of songs with a sterling variation of interludes. He’s driving force and snappy accompanist in-one. Danger hi-voltage! You gotta watch out with Philly Joe, he’s like the professional oven I recently bought, it heats much quicker than the consumer type oven and is hazardous to the health of your hands but it is, most of all, state of the art. The roasted chicken is killer bee.

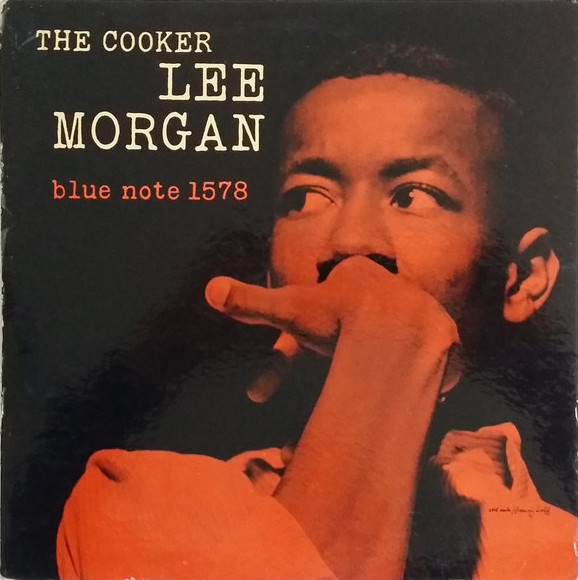

Take Philly Joe Jones’s Blue Gwynn. Afro-Cuban powerhouse performance. A couple of uppercuts and a sparse cluster of notes from Philly Joe launches the band into the stratosphere. It’s a crafty piece, largely through the balanced variety of the roles of reed, brass and woodwind during theme and intermezzos. However, the performance is far from contrived, indeed strikingly organic. Morgan, Golson and Fuller have their fiery say. Morgan’s entrance is typically cocksure. You’re gonna love this one.

The Eastern-tinged Land Of The Blue Veils by Benny Golson, ensemble playing sans solo’s, is like a Brussel bonbon that melts on your tongue. Philly Joe’s adaptation of Vincent Youman’s Carioca – El Tambores – is an exciting trip to Brazil quoting evergreen Tico Tico in the process. Ray Noble’s Cherokee gets a wooping treatment, including witty Indian war cries. The Tribal Message is Jones in African mood, a great display of varying pitch, echo and effects, which involved a careful placement of the parts of Philly Joe’s kit all over the studio.

And the American rhythm and harmony, sedimentation of a different array of African minerals and European metals and turned into a very special brew, is represented by Golson’s Stablemates and Philly Joe Jones/J.J. Johnson’s Philly J.J, both hard-swinging cookers. Brass and reed figures stimulate the soloists of Stablemates, of which Golson is particularly heated. Philly Joe sets fire to Philly J.J.. The introduction (this is a record of introductions) by Jones is as filthy as they come, the language of a hustler taking care of business at the corner of Lexington and 110th Street. His rolls and snappy hi-hat crushes may be interpreted as having their origins in tribal communication and prefiguring rap music and at the end of the furious performance, no doubt it’s a wrap. Now you remember why Miles Davis wanted no one but Philly Joe for his First Great Quintet in 1956. Another Davis associate of that period, Cannonball Adderley, also excites considerably during Philly J.J. with his sole solo performance of the session. Philly J.J. is not blowing session fare. There’s a switch from breakneck speed to mid-tempo bounce and a reference to the intro during the dramatic climax that suggests careful planning by the then 36-year old drummer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Did I tell you that Philly Joe sounds out of sight? Drums were meant to sound like this!

The way music sounds affects our evaluation of it. We can experience the pure sound of a musician in a live setting – although purity is a relative concept. At any rate, the musician has to wait and see how he or she sounds on record. Studio sessions involve the manipulation of sound. Whom manipulates sounds most expertly and tastefully gets the best results. That’s why the acclaimed Dutch engineer Max Bolleman pointed out that the engineer is a member of the band. His instrument is his console.

Drums, the heartbeat of the band, make or break a record. In the 20’s and early 30’s, primitive equipment did not allow the drummer to play as he did during performance, since it was at risk of exploding if the drummer pounded on a complete drum kit. Consequently, the drummer stuck to woodblocks and such, which is why we have to rely on oral history to imagine how, for instance, Baby Dodds sounded in the early part of his career.

This hardly bothered modern drumming. The 50’s and 60’s are sublime drum decades. By then, engineering had developed rapidly and considerably. Wouldn’t we nowadays hold Baby Dodds in even higher regard if he would have had “his” Rudy van Gelder or Roy DuNann?

I’ve always had the distinct passionate feeling that drums never sounded better than approximately from 1955 to 1965. The updated analog equipment was nifty but its track limitations forced the engineer to be creative, unlike swing and bop, which was an improvement of the early years of jazz but still suffered from the occasional cardboard box sound. And unlike the 70s and beyond, when multi-tracking, a limitless array of mics and digital technology more often than not has led to visionless mediocrity. The 50’s/60’s sound may not be as detailed compared to the thoroughly improved contemporary sound, but the overall sound is killer and the impact unforgettable. Call me a purist but the way to go as far as contemporary mainstream jazz recording is concerned is to at least strive for that 50/60’s sound.

There are countless examples of great-sounding drum records from that era. Big Band Sounds is but one example but a damn great one – notice, the (sub-) title says ‘sounds’. The synthesis of sound and high-level modern jazz playing is sublime. Man, not only does Philly Joe Jones display his unsurpassed fiery style, his sound is absolutely stunning! And big – notice, the (sub-) title says ‘big’. Booming. Snappy. The engineer is Jack Higgins. A round of applause for Jack.

And on your hands and knees, seated in the direction of the Mecca of jazz, for Philly Joe.