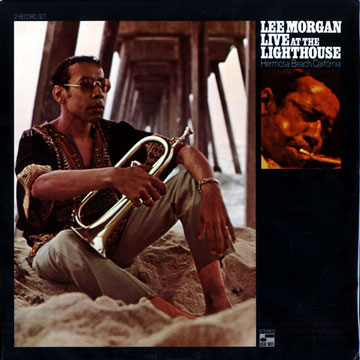

The titles of Lee Morgan’s Live At The Lighthouse, such as Nommo and Neophilia, perfectly match the woolly times. Sounds like books by Madame Blavatsky read by a wicker man under the sole tree in Greenwich Village, while runaway girls in gingham dresses rattle their gypsy earrings and recite luney banjo tunes with feverish enthusiasm… Indeed, Morgan’s notes sometimes are close to hitting a falling star but underneath his ‘pretty far out’ project shimmers the trumpeter’s trademark hard bop blowing.

Personnel

Lee Morgan (trumpet), Bennie Maupin (tenor saxophone, bass clarinet), Harold Mabern (piano), Jimmy Merritt (bass), Mickey Roker (drums)

Recorded

on July 10-12, 1970 at The Lighthouse, Hermosa Beach, California

Released

as BST-89906 in 1971

Track listing

Side 1:

Absolutions

Side 2:

The Beehive

Side 3:

Neophilia

Side 4:

Nommo

The prince of hard bop’s more adventurous side occasionally came out of hiding, less than Lee Morgan wished, I guess. Sure, as early as 1963, Morgan was featured on Grachan Monchur III’s avantgarde outing Evolution and the trumpeter’s follow-up of hit album The Sidewinder, 1964’s Search For The New Land never lost anything of its frontline charm. He appeared on Wayne Shorter’s Night Dreamer, Joe Henderson’s Mode For Joe and Andrew Hill’s Grass Roots and Lift Every Voice. But as far as leadership dates were concerned, Morgan’s label, Blue Note, still favored straightforward jazz releases in the late sixties over envelope-pushing affairs, some of which were released posthumously, such as The Sixth Sense and The Rajah. Then there was Live At The Lighthouse, subconscious-Lee in the limelight at last. By that time, of course, Alfred Lion was taking pictures in Mexico and Blue Note, though Francis Wolff and Duke Pearson shared production responsibilities, was swallowed by United Artists.

Scene of the spectacle: the legendary Lighthouse, hurled into prominence in 1952 by Howard Rumsey but, as Dutch journalist Jeroen de Valk revealed in his 1989 mythbusting biography of Chet Baker, in reality put on the map initially by Baker just before Rumsey came into the picture. A rather unspectacular club that hosted legends like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan, Cannonball Adderley and many others. Situated close by the beach, where Lee Morgan sat beneath the poles of the pier some time between July 10 and 12, 1970, a time sequence in which the wind blew a hodgepodge of moody and explosive trumpet and sax sounds outwards from the bowels of The Lighthouse over the sweaty, salty Hermosa shore. Lots of seagulls, their obnoxious squawks momentarily stunned.

The stress is on vamp, modality, mood. Music that challenges you to surrender to its spiritual cry and moan. It’s tenorist, bass clarinetist and flutist Bennie Maupin that ‘moans’ most convincingly. No doubt, Lee Morgan blows spirited trumpet and builds crafty stories, but while Morgan focuses on recurring figures and effects like the halve valve trick, Maupin sends us unpredictable weather from his throne above the clouds, alternating deadpan turns, bluesy phrasing and torrents of edgy Coltrane’s sheets of sound preceding the release of dark-hued calm-after-the-storm notes. His feature on bass clarinet on Neophilia, a lullaby-ish, concise and plainly beautiful, slow-moving melody, goes from sweetness to drama, climaxing with violin-like cries. Maupin, nowadays going strong at the age of 76, came into prominence with Horace Silver in ‘68/’69, Lee Morgan in ‘68/’70, Woody Shaw in ’70/’72, played on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew and was a long-time part of Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi band in the late sixties and early seventies. His 1974 album on ECM, The Jewel In The Lotus, is a treasured album for avant-leaning jazz fans. Cutting edge cat.

A great band with writers Morgan could benefit from. Harold Mabern’s The Beehive’s a short, quirky theme, like a fragment from a Charlie Parker solo, alternating between the fragment and Mickey Roker’s ferocious drums breaks. Jimmy Merritt’s strangely beguiling Nommo switches between a soulful line and elegiac intermezzo, building on a twisted boogaloo vibe and Roker and Merrit’s hefty cross-rhythm. The a capella sections of Morgan and Maupin before returning to the theme are thoroughly enjoyable. Another Jimmy Merritt tune, Absolutions, showcases the group’s dynamic prowess, squeezing every bit out of the modal vamp, pushing and pulling at time’s rear end until it, like time seems to have been doing eternally, bends. Morgan is terrific, translating the military-rolls of a snare drum to the trumpet, and charmingly experimenting with the various shades of softness and loudness.

Strictly vinyl on Flophouse’s smoky Monte Christo #2 premisses. But just this once, an exception, since the Compact Dick not only offers more avant-leaning, uptempo jazz that for the most part would easily have stood the test of LP release, but also brings a version of The Sidewinder, the hit that Morgan almost hated more than Trump fans hate reason. Table three was requesting a tune, perhaps. The group’s turning in a solid take.