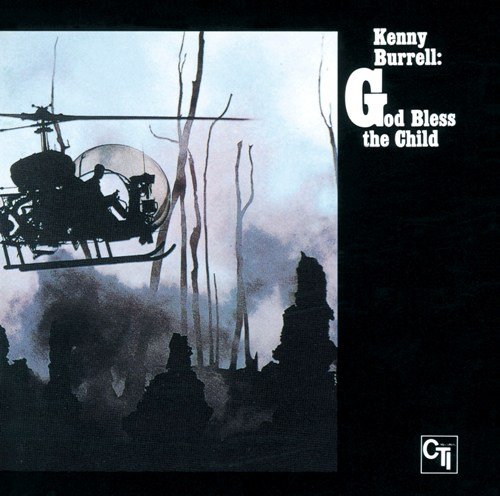

Naming a record God Bless The Child inevitably brings forth a lot of expectations. Could one live up to them after re-imagining the touching version of the song’s composer Billie Holiday – she and co-writer Herzog Jr. wrote about a subject matter close to her vest – and the haunting, deconstructive solo rendition of Eric Dolphy? It’s not easy, and it seems that for Kenny Burrell, it was just another lovely tune and he’s not really into it – and for producer Creed Taylor just another song allowed to be buried in schmaltzy cello sections.

Personnel

Kenny Burrell (guitar), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Hubert Laws (flute), Richard Wynands (piano, electric piano), Hugh Lawson (electric piano), Ron Carter (bass), Billy Cobham (drums), Ray Baretto (percussion), Airto Moreira (percussion), Seymour Barab, Charles McCracken, George Ricci, Lucien Smit, Alan Schmit (cello section), Don Sebesky (arranger, conductor)

Recorded

on April 28 and May 11 & 25, 1971 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as CTI 6011 in 1971

Track listing

Side A:

Be Yourself

Love Is The Answer

Do What You Gotta Do

Side B:

A Child Is Born

God Bless The Child

It’s not a total failure. After all, it’s Kenny Burrell. Having been much admired by critics and public alike a decade before turning over this album, Burrell felt comfortable in many surroundings and delivered countless memorable contributions to the straight, bluesy, bossa and comparatively adventurous sides of jazz. God Bless The Child has its moments and they invariably have to do – as opposed to a multitude of strings, keyboards and percussion – with Kenny Burrell’s many fine licks.

One can do without the generic world music jam of Love Is All The Way, but Burrell’s solo runs sound like exotic alleyways that always seems to lead to an opening in the labyrinth. The crisp and clear Do What You Gotta Do wouldn’t have been out of place on one of Burrell’s career peaks, 1963’s Midnight Blue, if it wasn’t for five cello’s moving in straight from a Mel Torme delivery truck.

Burrell’s best soloing is heard in Be Yourself; it’s inventive and typically Burrell – he doesn’t throw it at you in bold strikes but instead tells a story in a laid-back yet exciting way. Unfortunately, Be Yourself gets the same string treatment as the rest of the album. By this time, the album’s production has dulled the senses considerably.

God Bless The Child is almost as much a Creed Taylor record as it is a Kenny Burrell record. Taylor, imperative in moving jazz forward with his production and A&R work for Impulse and Verve, was very succesful in transforming the paths of sixties luminaries into lucrative endeavors by means of his own company Creed Taylor Inc. Musicians (although sidemen sometimes have a different story to tell) were glad of it – $! – and rightfully so, they had to make a living. The downside of CTI was that Taylor was a man who liked to be in control. More often than not, the net result of such an abundance of money and control in music biz, particularly onwards from the early seventies, has been indulgence; suddenly there are myriad possibilities production and personel-wise (multitrack consoles, strings and brass-sections, two or more percussionists, keyboard-landscapes) and they more often than not tend to lead, in my view, to a creative void and sterile recordings. The finest recordings, on the other hand, are often born out of necessity – relative lack studio time and personel, more primitive equipment – which pipes up expressiveness.

One outcome of Creed Taylor’s overpowering presence in the dollar department and control room was on my turntable. It’s bland, slick. It was a career boost for Kenny Burrell, but not an album to fondly remember and be fondly remembered for.