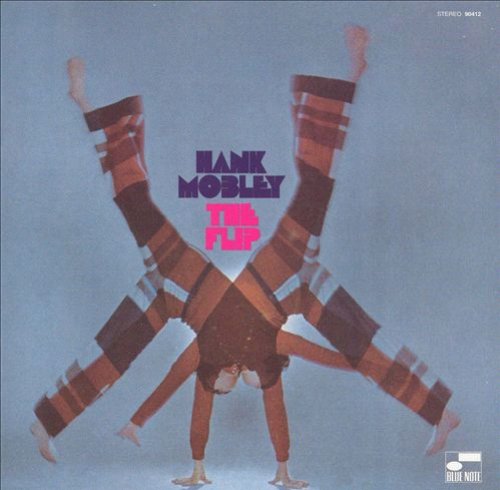

In the late sixties Hank Mobley’s round tone had become a bit rougher around the edges and his style was more hard-driving. This is evident on 1969’s The Flip, which boasts hi-voltage blowing but is short on finesse. Mobley, always the prolific songwriter, wrote all five tunes on The Flip. The compositions that turn out best are the ones that resemble Mobley’s songwriting of the late fifties and early sixties.

Personnel

Hank Mobley (tenor saxophone), Dizzy Reece (trumpet), Slide Hampton (trombone), Vince Benedetti (piano), Alby Cullaz (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Recorded

on July 12, 1969 at Studio Barclay, Paris, France

Released

as BST 84329 in 1969

Track listing

Side A

The Flip

Feelin’ Folksy

Side B

Snappin’ Out

18th Hole

Early Morning Stroll

Examples of the latter are

Feelin’ Folksy,

18th Hole and

Early Morning Stroll.

Feelin’ Folksy swings suavely and is a coherent group effort. Mobley’s solo is a mix between his earlier bluesy style and new, more advanced bag. Clearly, Mobley is in fine form, in spite of the increasing alcohol abuse of that time in his life. Late 2014, I talked to Dutch pianist

Rob Agerbeek, who toured in Europe with Mobley in 1968/69 and remembered that Mobley was playing very well indeed. Incidentally, Mobley wanted Agerbeek to play on the sessions of

The Flip in Paris, but Blue Note boss Francis Wolff had already booked Vince Benedetti, so Agerbeek had to be cancelled.

18th Hole is an intricate, hard-swinging tune with great three-horn harmony. Philly Joe Jones keeps the guys on their toes, especially in Early Morning Stroll, a bop figure that makes good use of tension and release with an lengthy bridge.

Hank Mobley’s the quintessential musician’s musician. That isn’t front page news. Key words: killer chops, smart songwriting, unique round, warm tone, inventive storytelling, smokin’ hot to boot. Great storytelling, however, has become a minority on The Flip. More often than not, Mobley reaches an early climax in his solo’s, which doesn’t leave much room for a story to develop. Where to go when the gunpowder has faded?

To my pleasure, on Early Morning Stroll, Mobley cuts short his initial flurry of over-excited notes and instead tells an interesting, swinging tale. Trademark Mobley.

Snappin’ Out is a typical Latin hard bop tune and an easy head to blow on. Slide Hampton blows swift and assured. The tune is more satisfying than the title track and opener of the album, The Flip, which, arguably, is a conscious effort to reach the same popular status as Mobley’s earlier winner of 1965, The Turnaround. But conscious efforts, like femme fatales, rarely give you what you want.

The Flip swings hard and is sure to enliven a party. But unfortunately, it also swings wild and uncontrolled, favouring a strained, hi-octane tension over a sophisticated build-up. If Philly Joe Jones would be alive today to comment on The Flip, I’m sure he would agree that boogaloo wasn’t his long suit. I’m sure he would laugh and say, ‘Man, I better stick to modern jazz drumming, leave that boogaloo to Idris Muhammad!’ Jones possessed the humor and self-mockery. The drum legend faultlessly imitated Bela “Dracula” Lugosi on a 1958 Riverside album, remember.

Speaking of faultless jobs, considering Mobley’s abilities The Flip is quite a distance away from douze points.