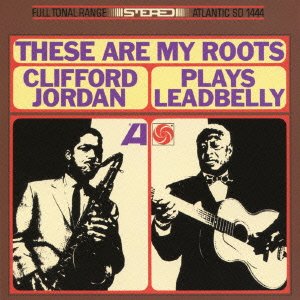

The Mosaic label, whose policy of re-issueing and uncovering vaults has been so essential in keeping the flame of classic jazz burning, shed a welcome light last year on tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan, releasing a box set of six adventurous albums Jordan produced and recorded in the late sixties and early seventies on Strata-East, among them Jordan’s career-defining 1973 album Glass Bead Games. Jordan’s career included other rewarding efforts, like These Are My Roots: Clifford Jordan Plays Leadbelly, Jordan’s sole album on Atlantic. It’s a surprise act, a wicked dedication to the roots of black musical culture.

Personnel

Clifford Jordan (tenor saxophone), Roy Burrowes (trumpet), Julian Priester (trombone), Cedar Walton (piano), Chuck Wayne (banjo), Richard Davis (bass), Albert Heath (drums), Sandra Douglas (vocals A3, B3)

Recorded

on February 1 & 17, 1965 in NYC

Released

as SD 1444 in 1965

Track listing

Side A

Dick’s Holler

Silver City Bound

Take This Hammer

Black Betty

The Highest Mountain

Side B

Good Night Irene

De Gray Goose

Jolly ‘O The Ransom

Yellow Gal

Jordan hailed from Chicago, hometown of hard-driving, so-called ‘tough tenorists’ like Gene Ammons and Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis. While Jordan shared their unnerving bravado, his tone is different, an alluring tone, simultaneously rough around the edges and ephemeral. A sought-after sideman, Jordan recorded with stalwarts as Lee Morgan and Max Roach in the late fifties and early sixties, as well as a series of high standard solo albums. Much acclaimed hard bop favorites are Blowing In From Chicago (Blue Note, 1957, with John Gilmore) and Cliff Craft (Blue Note, 1957) Like age matures wine, Jordan’s style ripened in the early seventies, his lines becoming fluent like ripples of lake water. Jordan kept recording and performing steadily until his death in 1993.

Maybe this album, filled with interpretations of such classic tunes as Take This Hammer and Goodnight Irene, is not such a surprise act after all. The preceding year, Jordan had been part of Charles Mingus’ outfit (appearing on the hi-voltage live album Right Now: Live At The Jazz Workshop) Musical gobbler Mingus’ unfazed search for new vistas while retaining an all-embracing sense of the past’s relevance and blend of harmonic finesse with unbridled juke joint tumult surely rubbed off on Jordan.

Da Gray Goose is one of the cases in point. Tasteful harmony over the stop-time theme kicks it into action, strongly plucked bass and fiery drums inspire the soloists, creating an atmosphere of abandon. Lusty shout choruses stoke up the fire as the tune progresses. There are also some, yes, virtuoso banjo parts.

The gloomy folk blues music of Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter, whose life story reads like a combined effort of Shakespeare and James Baldwin, including oppression, hardship, addiction, treachery, murder and prison life, is excellently cast in a jazz frame. But not too jazzy, often the sound of Jordan’s top-notch group is as tough-as-nails as the sound of any one group that enlivened the back alley bars way back when. Jordan’s unpredictable phrasing overcomes the restrictions of the rigid folk blues form.

Craftily uncrafted, These Are My Roots is a spirited album of earnest, raw and ebullient swing.