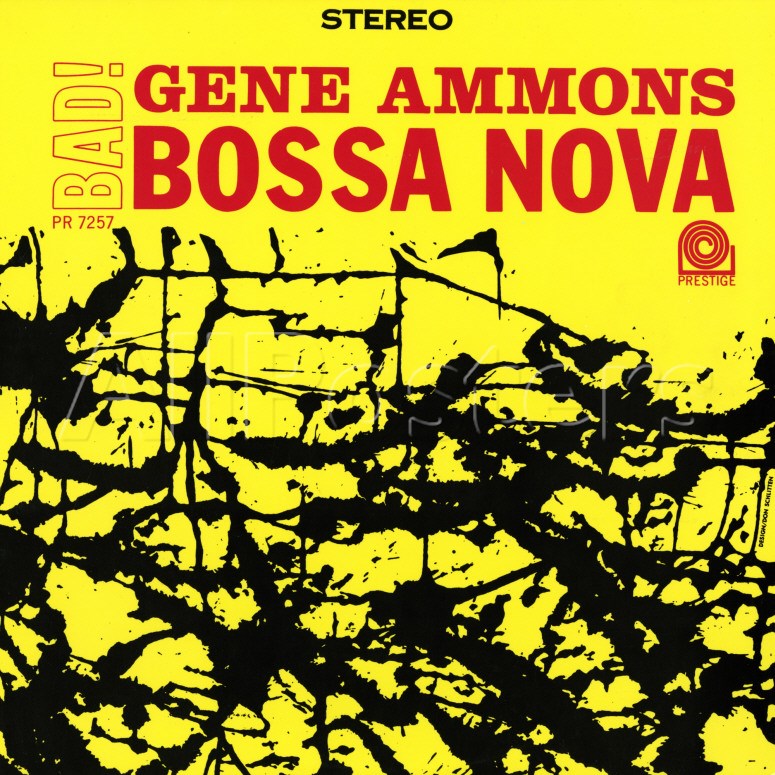

Throughout his spectacular career, tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons had several big hits, both singles and albums. One of those albums, Bad! Bossa Nova, paved the way for soulful players intent on exploring Latin music.

Personnel

Gene Ammons (tenor saxophone), Hank Jones (piano), Bucky Pizzarelli (acoustic guitar), Kenny Burrell (acoustic guitar), Norman Edge (bass), Oliver Jackson (drums), Al Hayes (bongo)

Recorded

on September 9, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7257 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Pagan Love Song

Ca’ Purange

Anna

Side B:

Cae, Cae

Moito Mato Grosso

Yellow Bird

After organist Jimmy Smith, who was second to none as far as popularity and record sales was concerned, Gene Ammons was another very succesful artist of the soul jazz era. Ammons started out in the bands of King Kolax and Billy Eckstine in the mid-forties, the latter a playing ground for the burgeoning bebop generation of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Wardell Gray, Fats Navarro and Art Blakey. And Ammons, who knew his share of bebop. During his tenure with Eckstine, Ammons’ colleagues in the reed chair were Dexter Gordon, Leo Parker and Sonny Stitt. As a leader, Ammons gained a lot of public acclaim with the jumpin’ blues theme Red Top in 1947. The tenor saxophonist subsequently struck gold with the ballad My Foolish Heart in 1950, one of the tunes in the borderland of r&b and jazz (the distinction wasn’t as evident then as it is now) that many jazz artists of the day specialized in. During the years 1950-52, Ammons made up an explosive sax battle team with Sonny Stitt, whom he would keep recording with on and off through the sixties.

Ammons, the Chicago-born son of boogiewoogie master Albert Ammons, wasn’t about to slow down, if only by long, intermittent stints in jail for possession of drugs. Ammons has recorded for Savoy, VeeJay, Argo, but was part of the Prestige roster early on, an association that would continue throughout his career. His ‘HiFi’ jam albums of the late fifties with the likes of John Coltrane, Jackie McLean, Mal Waldron and Art Taylor were attractive but curtailed the playing time of the big-toned tenorist. His style would come fully to the fore on the big-selling Boss Tenor in 1960, which spawned another jukebox hit, Canadian Sunset, as was Exactly Like You from 1961’s Jug album. The fruitful period 1960-1962 secured Ammons’s top ranking in soul jazz history. Bad! Bossa Nova is the last in line, since Ammons was convicted again, now also for selling drugs. It looked like the authorities wanted to set an example by sentencing the black jazz musician to seven years in jail. A great tragedy for Ammons and an utter disgrace which black people, unfortunately, have been all too familiar with. His comeback on Prestige in 1969 would be very successful. But his conditions worsened and Ammons passed away in 1974 at the age of forty-nine.

Unabashed emotion. A big sound that fills the (bar-)room. Excuse me? A soccer stadium! Great storytelling abilities. A tough tenor that wails with the best of ‘m but with controlled power. A prime balladeer. And a great entertainer. The title of Bad! Bossa Nova sounds about right. Bad it is. Ammons wholeheartedly funkifies the set of Latin-tinged tunes. If it doesn’t exactly consign Stan Getz/Charlie Byrd’s Jazz Samba album, containing the hit Desafinado, released half a year earlier, to the litter bin, after a back-to-back spin Getz/Byrd’s album certainly comes across as shopping mall muzak. Both albums were big sellers, Jazz Samba foremost, but Bad! Bossa Nova sold large quantities in black neighbourhoods. A couple of years later, while Ammons was doing time, it was re-issued by Prestige as Jungle Soul and again sold extremely well!

Highlights are Ca’ Purange and Cae, Cae. Ca’ Purange (Jungle Soul), a simple recurring Latin figure, is a perfect canvas for Ammons’ bold strokes. His tone fills the sky, sparse, long lines and staccato honks stoke up the fire, which threatens to overrun the swamps, where Gene Ammons’ greasy, hypnotic soul groove is pulling you in anyway. A dense rhythm section including Kenny Burrell as acoustic rhythm guitarist lays down a colorful groove for Ammons, with guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, also on acoustic guitar, occasionally chiming in with spicy licks. Hank Jones is an extra treat. The masterful pianist delivers deliciously swinging, delicate miniatures, pulling out all the happy-go-lucky stops with locked-hands technique and notes tumbling over each other like kittens reaching for the milk at the nipples of pussy mom in Cae Cae particularly. Hank Jones, early bebopper, modern jazz giant probably best known for his role on Cannonball Adderley’s Something Else, knows how to play popular music, having operated in the shadowlands of jazz and r&b in the early fifties, notably on organ. Gene “Jug” Ammons is a true master of blending sophistication with entertainment which Bad! Bossa Nova makes abundantly clear.