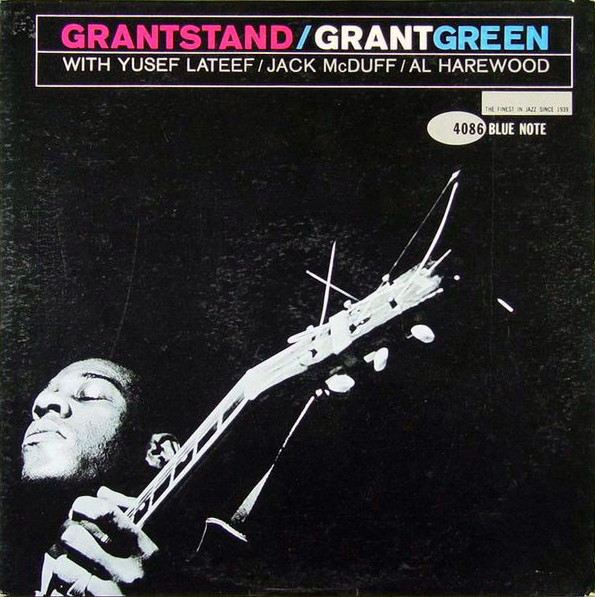

Grantstand ranks among guitarist Grant Green’s finest dates. A gathering of aroused spirits in Rudy van Gelder’s famed Englewood Cliffs studio.

Personnel

Grant Green (guitar), Yusef Lateef (tenor saxophone A1, B1, B2, flute A2), Brother Jack McDuff (organ), Ben Tucker (bass), Al Harewood (drums)

Recorded

on August 1, 1961 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 4086 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Grantstand

My Funny Valentine

Side B:

Blues In Maude’s Flat

Old Folks

Green, the most prolific Blue Note artist of the early and mid-sixties, was just shy of his second year as a new guitar man on the NYC block. He was in great company. Tenor saxophonist and multi-horn player Yusef Lateef would join Cannonball Adderley’s group in late december of 1961, staying till 1964. Green is further assisted by organist Brother Jack McDuff, the second time they cooperated, the first being McDuff’s The Honeydripper, recorded half a year earlier on February 1 on Prestige. Drummer Al Harewood was regularly featured on straightforward Blue Note recordings, notably as a member of the in-house trio Us Three which further consisted of pianist Horace Parlan and bassist George Tucker.

Good vibrations. Sparkling shreds of fire shooting upwards, curling around the beams of the RVG Studio’s high-domed, temple-like ceiling. A set of smokin’ blues tunes alternated with a melancholy ballad and a sprightly standard. Wrap it in shiny paper, lace it up and send it to your closest jazz pal with best wishes. Grantstand, the title track, bubbles, sizzles like a copious amount of ribs on a Saturday night BBQ. Hungry men. They tackle the uptempo, catchy blues riff like wolves jumping the lamb. The band catapults Green into action and stimulates the blues-drenched, former St. Louis citizen to fire off razor-sharp lines, adding slightly slurred, repeated phrases for dramatic effect. Green provides crunchy chords and plucky bass lines behind Yusef Lateef, who excels with a relaxed, down-home and layered tale, the chapters are recited without hurry, slowly but surely gathering momentum.

And the sound of these guys! Green: sustained, shimmering, fluid gold. Lateef: resonant, full-bodied, grandaddy-puffs-on-a-cigar-sound. McDuff chimes in with the roar of the minister, spitting a sermon into the faces of the flabbergasted flock. Intriguingly, McDuff succeeds to marry the gospel with the spirit of pure-bred rock&roll.

A bouncy version of Old Folks and a classy take on My Funny Valentine add variety to Green’s repertory, while Blues For Maude’s Flat continues the dip into bluesland. After hours vibes. The juices are flowing, the bottle of moonshine’s nearly empty. It could very well be that Green, Lateef, and McDuff arrived in New Jersey fresh from a gig in one of those dingy clubs the giants of jazz made their money in back then, like Chicago’s Theresa’s Lounge, Newark’s Front Room or Lennie’s On The Turnpike in Peabody, Massachussets. Blues In Maude’s Flat is a slow walk with a canny intermezzo of tension and release that serves as a springing board for the vibrant bunch of Lateef, Green and McDuff. Tenor/organ combo stuff of the grittiest and highest order, with the propulsive, already very authoritative leader on top of his game.