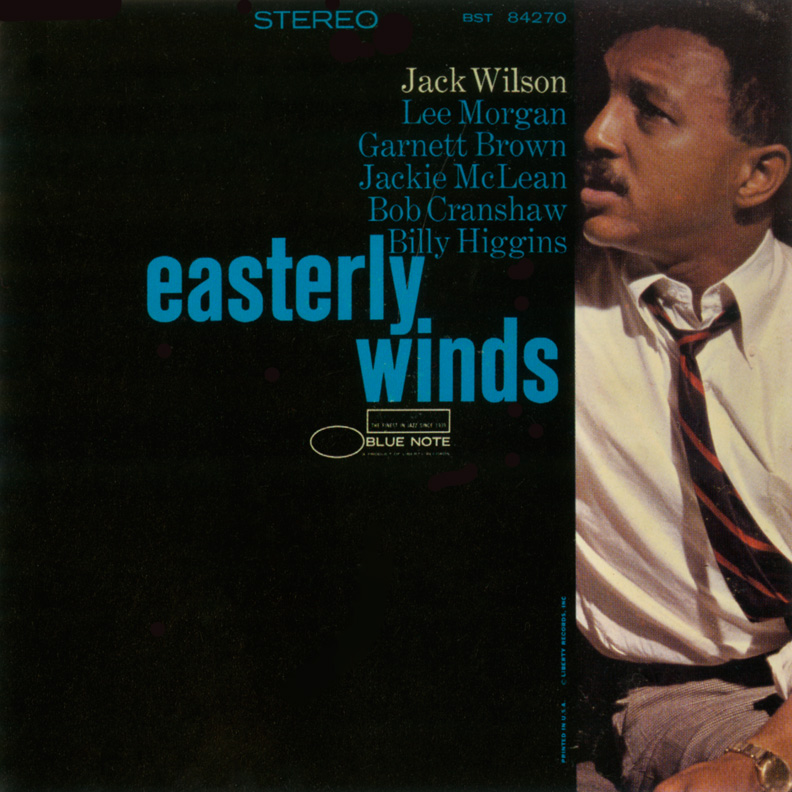

In the epic menu of classic Blue Note albums, Jack Wilson’s Easterly Winds is easily overlooked. It’s an all-round gem including the frontline of trumpeter Lee Morgan, alto saxophonist Jackie McLean and trombonist Garnett Brown.

Personnel

Jack Wilson (piano), Lee Morgan (trumpet), Jackie McLean (alto saxophone), Garnett Brown (trombone), Bob Cranshaw (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded

on September 22, 1967 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BST 84270 in 1967

Track listing

Side A:

Do It

On Children

A Time For Love

Side B:

Easterly Winds

Nirvanna

Frank’s Tune

Perhaps the times were such as to be overlooked, 1967 being the year John Coltrane died, exactly a day after Wilson’s session, jazz temporarily in a state of paralysis. The superb but straightforward hard bop album was in the ring with the avant-garde outing, a darling of many critics, with an edge as, well… new. Everybody was waiting for Miles Davis to fabricate a fresh piece of inventive jazz cake. But why not simultaneously enjoy ‘old’ and ‘new’? Easy for me to say, fifty years after the fact. Thanks to Michael Cuscuna, Mosaic Records boss and remastering executive of the Blue Note catalogue, modern jazzy mankind has been giving the opportunity to enjoy remastered albums for many years now, with Cuscuna providing, while the ageless prima donna Blue Note hardly needed plastic surgery, a healthy shot of botox nevertheless.

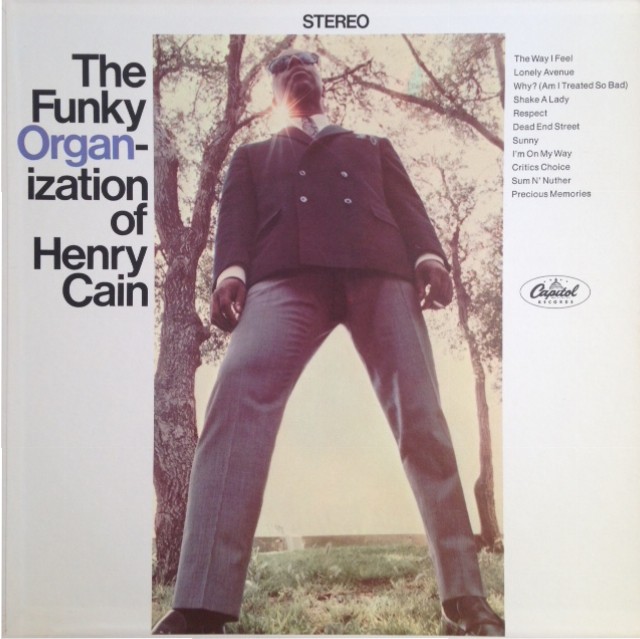

Jack Wilson, born in Chicago in 1936, enjoyed a long stint with Dinah Washington from 1957 till ’62. Moving around quite a bit, from Chicago to Atlantic City and Los Angeles to New York City, Wilson played with Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Eddie Harris, Jackie McLean, Johnny Griffin, Lou Donaldson and Gerald Wilson, featured on six of the latter’s Pacific Jazz albums. Charmingly ambidextrous, Wilson recorded, among others, his avant-leaning debut album Ramblin’ Featuring Roy Ayers (Atlantic, 1963, total winner!), The Jazz Organs (Vault, 1964, organ porn! Hammond B3 threesome with Henry Cain and Genghis Kyle! Wilson played organ as early as 1955 in Atlantic City, around the time Jimmy Smith kicked up a storm) and Easterly Winds, hard bop Blue Note magic for the ages.

Always the crafty sound sculptures and well-chosen variety of repertoire at the legendary record company. The big frontline, Morgan, McLean and the added thickness of Garnett Brown’s trombone. Wilson knows how to let it flow smoothly, as during the lovely melody of Frank’s Tune, styled in ensemble precisely and soulfully. McLean plays as if he’s eligible for parole, a touch of bitterness and acid still in his sound, which is nonetheless marked mostly by sardonism, relief, gladness to finally wave the warden goodbye. His lines are fluent, and air’s in between them also. Garnett Brown is not only an asset during the ensembles, but a terribly swift and funky soloist. Lee Morgan, one of Alfred Lion’s dream candidates, in possession of abundant versatility, funkiness and a hip and modern approach to make any Blue Note session a success, injects tart tenderness into the date’s mood piece, the haunting Nirvanna. He also travels along Funky Broadway during the album’s opening tune, Do It, a boogaloo groove set up by Billy Higgins. Yes, Billy Higgins, the one who provided an identical, tacky beat to Lee Morgan’s hit The Sidewinder from 1964. Three years after the fact, Do It is just as grittily swinging as that tune, deserving equal praise.

The title track is the album’s uptempo winner, another gem added to the long list of hard bop jewelry in the Blue Note vaults. Wilson, a man who just as easily conjures up the understated drama of Nirvanna through a series of arpeggios, tremolos and bold chord clusters, during Easterly Winds displays legato pureness and kilometers of fecund lines, somehow finding a way out of the stormy labyrinth. It always remains very special to hear the coupling of gifted musicians with the amazing production standards of the Blue Note label.