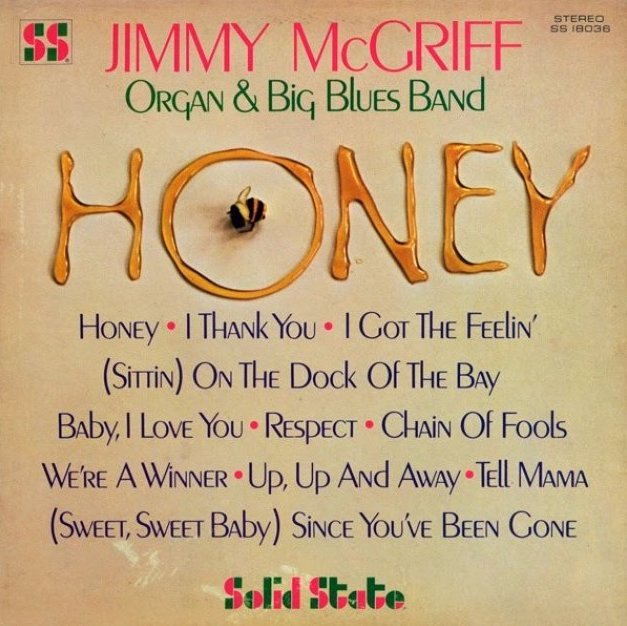

You can pick your favorite soul tune from Jimmy McGriff’s 1968 Honey album and dance, dance, dance.

Personnel

Jimmy McGriff (organ), Uncredited ‘Organ & Big Blues Band’

Recorded

in 1968 in New York City

Released

as SS-18036 in 1968

Track listing

Side A:

(Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You’ve Been Gone

Respect

Chain Of Fools

We’re A Winner

Up, Up And Away

Side B:

Tell Mama

Honey

I Thank You

I Got The Feelin’

Baby, I Love You

(Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay

It’s a blatantly commercial album by McGriff, who was quite popular ever since the organist from Philadelphia scored a hit on Sue Records in 1962 with Ray Charles’ I Got A Woman. Switching to Solid State in 1966, McGriff’s version of Cherry did very well on the charts. Producer Sonny Lester must’ve dreamt of making McGriff just as famous as his mentor and friend, Jimmy Smith, who was the most popular soul jazz artist of the era, more so after he switched from Blue Note to Verve, under the guidance of Creed Taylor. Sonny Lester used McGriff in a variety of settings, from blues, pop to big band, some more successful than others. Essentially, Honey presents a rather arbitrary choice of popular soul tunes. Just put ‘m all on one album, see which one picks up any airplay.

But. Big but. Although it would’ve been nice if McGriff had recorded more often in a modern jazz setting in the sixties, (McGriff’s albums on Milestone in the 80s and 90s are more jazz-oriented) McGriff’s clever voicing and modern approach have not altogether vanished from his chart-running songbook. Besides, McGriff is a blues master that rarely disappoints in the kind of setting Honey represents. He is, after all, a groove monster without peer!

The album is a mix of uptempo classics like Respect, Chain Of Fools, I Thank You, medium-tempo tunes as (Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay, James Brown’s funky I Got The Feelin’ and the odd pop tune, Jimmy Webb’s Up, Up And Away. Throughout, McGriff’s charming mix of screamin’ blues riffs and dazzling little bop lines keeps the listener on his toes. His timing is hip, floating around the beat. The band is seriously rocking, backing McGriff as if Otis, King Solomon or the Wicked Pickett is holding the mic. The sax player has no inkling to play ‘safe’ soul licks but instead – a pleasant surprise – injects cookers like Honey with tantalizing modern-jazzy phrases on what sounds like the electric Varitone saxophone. The group is uncredited. It might be saxophonist Fats Theus, who played on McGriff’s The Worm in 1968 as well.

Honey paid the bills. In later life, McGriff kept gigging steadily, making a living on the road. A while ago, the late flutist, saxophone player and educator Peter Guidi recounted his stint as a sideman with McGriff to Flophouse, describing the traveling organist’s classy van as a bonafide ‘mobile bordello, laced with red velvet’. It also carried the Hammond B3 and indispensable Leslie speaker. Guidi remembered the day McGriff offered him a gig, but Guidi, who almost once got killed carrying a B3 down the stairs of a club, said: “I love your work and I want the job. As long as I don’t have to carry the damn thing!” McGriff laughed. Guidi got the gig anyway.

It is a blessing that, in spite of the machine’s awkward shape and elephantine weight, there have been so many fine organists. Jimmy McGriff definitely was one of the leaders of the pack.

The full album is on YouTube. Listen here.