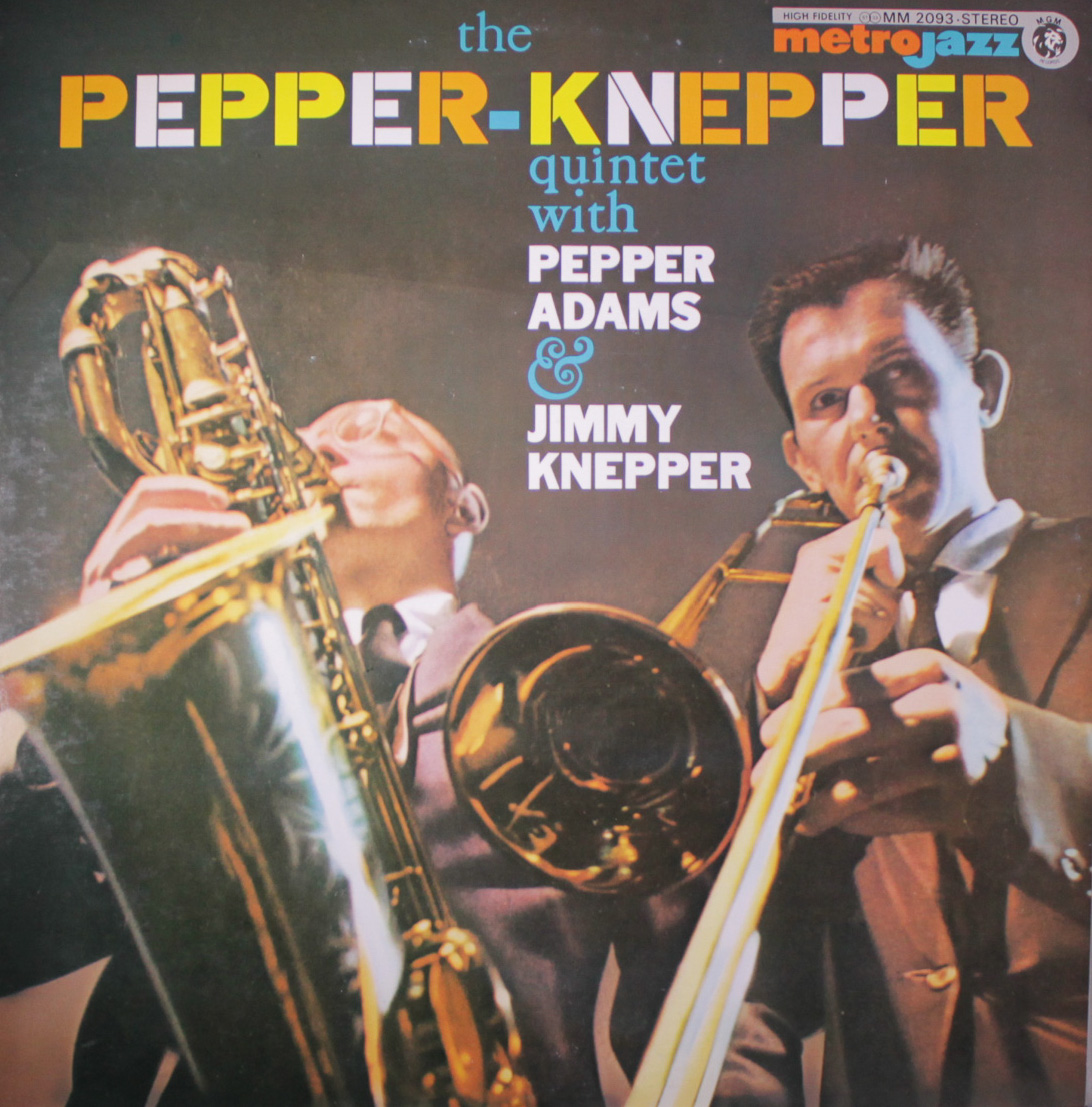

The legacy of the short-lived group of baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams and trombonist Jimmy Knepper consists of one excellent hard bop album, The Pepper-Knepper Quintet.

Personnel

Pepper Adams (baritone saxophone), Jimmy Knepper (trombone), Wynton Kelly (piano, organ B2), Reggie Workman (bass), Elvin Jones (drums)

Recorded

on March 25, 1958 at Beltone Studios, New York City

Released

as MetroJazz E1004 in 1958

Track listing

Side A:

Minor Catastrophe

All Too Soon

Beaubien

Adams In The Apple

Side B:

Riverside Drive

I Didn’t Know About You

Primrose Path

First of all, the album title sounds great: The Pepper-Knepper Quintet. Doesn’t it? Let it roll on your tongue: The Pepper-Knepper Quintet….

Most importantly, this group, also consisting of pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Elvin Jones, swings its set of hard bop to the ground, adding to it a couple of fine original tunes. Adams and Knepper parted ways soon after they joined forces in 1958. However, Adams held on to the rhythm tandem of Doug Watkins and Elvin Jones, added pianist Bobby Timmons and formed a frontline with trumpeter Donald Byrd, the outfit that recorded the top-notch live album 10 To 4 At The Five Spot a month after this session in April, 1958.

Nobody like Pepper Adams, descendant of bop bari greats Leo Parker, Serge Chaloff, king of hard bop baritone sax playing. Little man with big lungs, Adams barks like a hounddog, wails with balanced fury and is a meaty and lyrical balladeer of note. The valves rattle, meat and potatoes is his favorite dish, backrooms laced with red velvet his natural habitat… Pepper Adams strikes a perfect balance between sleaze and purity.

Knepper is part of the same generation, class act trombonist that played with Woody Herman, Gil Evans, Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. Most notably, he was part of Charles Mingus’s group from 1957 to 1961 and was featured on classic albums such as Mingus Dynasty and Mingus Ah Um. Ample reason to ah um. Bad-tempered Mingus punched Knepper in the face while rehearsing in the bassist’s apartment in New York City and broke his teeth. As a result, the embouchure of Knepper was altered, he couldn’t reach the upper octave for two years straight.

It was not the only altercation between Mingus and band members. One wonders how in the world our brilliant but nasty composer Mingus succeeded in recruiting first-rate musical staff time and again. What’s more, Knepper even returned for a stint with Mingus in 1978 and was part of the posthumous Mingus Dynasty band from 1979 to 1988. His teeth ok and Mingus k.o., this attitude succinctly points out Knepper’s uncompromising love and devotion for their mutual form of art.

The minor-keyed Adams In The Apple by Jimmy Knepper and the thoughtful melody and interesting harmony of Riverside Drive by Leonard Feather (Feather was the producer of this session) is fertile ground for the vigorous blowing of Adams and Knepper. Beaubien by Pepper Adams is a catchy blues riff. The beat, wonderful old-school drumming by Elvin Jones, is derived from jump blues and similar to the traditional tune of Hastings Street Bounce from 10 To 4 At The Five Spot. Most impressive is Wynton Kelly, master of mixing elegance with the down-home aesthetic of the juke joint. Kelly furthermore embellishes the Ellington ballad I Didn’t Know About You with orchestral accompaniment on the organ.

Primrose Path by Jimmy Knepper is the ear-catching climax of the solid The Pepper-Knepper Quintet. Like paragliders in the Alps, Adams, Knepper and Kelly navigate expertly and with hot swing through the breeze of the elongated, pretty melody, which subsequently changes keys during the secondary theme. Knepper revisited the tune on his 1980 album on the Scottish Hep label, Primose Path. Best tunes are – ask Monk – the ones that deserve refreshing readings.